I was recently short-listed in a contest for a piece of flash fiction entitled, ‘Last Night I Dreamed I Slept with Putin’. The story is absurd, comic, and ultimately tragic. I was told that it would be read by actors in Sydney alongside three other pieces and the winning story would be turned into a film. Unfortunately, just a few weeks before the performance, I received an email telling me my story had been withdrawn.

Even though the piece was ultimately critical of Putin, organizers said that people with family in Russia and Ukraine were ‘offended’. They felt that ‘because of the seriousness of the situation’ it wasn’t a ‘good time for comedic expression’ about Russia.

I certainly did not write the story to upset Ukrainians. I wrote it to explore the desires of an egomaniac dictator. I wrote it from the perspective of an everyday woman who wakes from her dream in February 2022 with ‘a vague notion’ that she’s ‘stopped a war’, only to read in the headlines that the war has just begun.

Just two weeks previous, I’d seen in The New York Times that best-selling American writer, Elizabeth Gilbert had ‘indefinitely delayed publication of her novel because it takes place in Russia’.

Gilbert must’ve spent years researching and writing that novel, which is extremely critical of the Soviet regime in Russia during the 20th century. But when people who hadn’t even read the novel started posting one-star reviews on Goodreads and claiming that it was offensive to write anything about Russia right now, Gilbert stopped publication of The Snow Forest.

Perhaps Ukrainians might’ve been offended by Gilbert’s novel or my story, and that’s certainly not something we desired or intended. When Gilbert pulled her novel, she said: ‘I do not want to add any harm to a group of people who have already experienced and who are continuing to experience grievous and extreme harm.’

'The gatekeepers have changed. Now any reader is a potential censor. A few tweets from an unknown person with extreme views can be shared and liked and cause a Twitter storm.'

That seemed a fair comment.

But then I remembered what a writer-friend, Amanda Niehaus, said two months ago (before Elizabeth Gilbert’s Russian novel debacle). We were at the Brisbane Writers Festival, speaking of banned books, and Niehaus said, ‘I wouldn’t want to write a book that didn’t offend anyone.’

This started me thinking about what writers are allowed to write in this current age when publishers are constantly worried about what might blow up on Twitter or Goodreads.

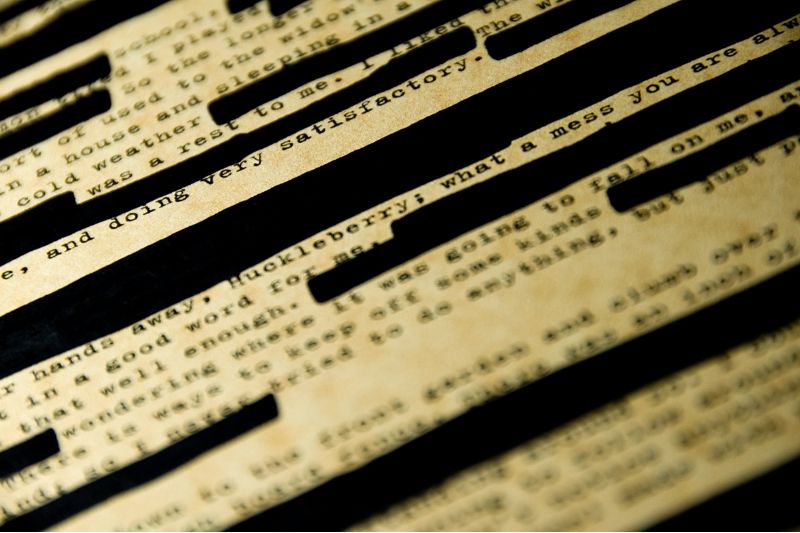

Censorship is as old as publishing, but we usually associate it with totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany or Mussolini’s Italy. Or contemporary Russia, where it’s very hard to publish anything that’s anti-Putin.

Still, you’d think that something criticizing Putin would be allowed to be published in Australia.

Imagine of Orwell hadn’t been able to publish Homage to Catalonia in 1938 during the Spanish Civil War because the book is darkly comic and absurd.

Suddenly, both here and in the U.S., we can’t write about Russia.

How did this happen?

The gatekeepers have changed. Now any reader is a potential censor. A few tweets from an unknown person with extreme views can be shared and liked and cause a Twitter storm.

In one way, this is could be seen as the ultimate democracy. Any one person has power. Every reader (or non-reader) is a book reviewer. But is that truly democratic? Even in democracy, there are checks and balances. In the unstable frenetic world of social media, any writer can be accused, tried and hung in a matter of minutes.

With studies showing that more extreme views are amplified on social media, who knows what will be censored next?

Francine Prose wrote last month in the Guardian that what is ‘unreasonable — and disturbing — is the precedent that Gilbert’s decision sets, the potential danger it poses to writers, to the future of literature, to the culture, and to our freedom of speech. What will happen if authors allow themselves to be bullied by their readers?’

At the end of the email telling me that my story about Putin had been withdrawn, the organizer of the contest wrote, ‘Best wishes — keep writing and stay creative!’

I still haven’t written her back. I’ve been having trouble writing anything at all. It’s difficult to be creative, when there is so much I am not allowed to say.

Sarah Klenbort is a writer and sesional academic at Queensland University, where she teaches creative writing. She also teaches memoir at the Queensland Writers Centre. Sarah's work has appeared in Eureka Street, The Guardian, Best Australian Stories, Overland and other publications here and overseas.

Main image: Getty images