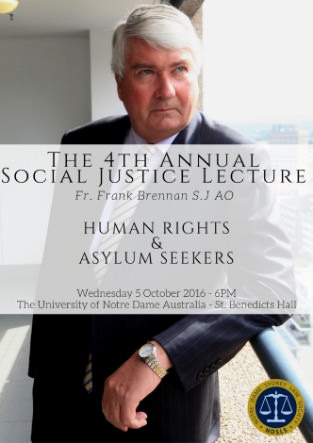

Address by Frank Brennan at the 4th Notre Dame Social Justice Lecture, University of Notre Dame, Sydney, 5 October 2016. Listen

The blind eyed Mr Turnbull at the UN

On 12 August 2016, well known media identity Andrew Denton addressed the National Press Club on the issue of euthanasia. Now that is not my topic this evening, and I happen to like Andrew. I enjoy his humour, I think he is very clever and I find him good company. However, I was very struck by a couple of his anti-religious, anti-Catholic sentiments. Looking back on lessons from previous euthanasia debates, he told the press club: [O]n the questions that are most fundamental to how we live, love and die, religious belief trumps everything. This is the theocracy hidden inside our democracy.'

He then urged: 'To those whose beliefs instruct you that only God can decide how a human being should die, I urge you, step aside. May your beliefs sustain you and those you love, but do not impose them on the rest of us.' He singled out Catholic politicians and Catholic businessmen for particular criticism. Like many commentators in increasingly secularist Australia, Mr Denton has a very simplistic view on the relationship between religious faith, law and public morality. Basically he thinks religious people have no role in the public square when it comes to contested moral issues and that it is only faith and not reason that informs the religious person's view of law and public morality. It's this insidious view 'hidden inside our democracy' which is contributing to us becoming a less caring society particularly when it comes to those who are 'other', those who are outsiders, those who are on the margins, and those who are weak and vulnerable.

He then urged: 'To those whose beliefs instruct you that only God can decide how a human being should die, I urge you, step aside. May your beliefs sustain you and those you love, but do not impose them on the rest of us.' He singled out Catholic politicians and Catholic businessmen for particular criticism. Like many commentators in increasingly secularist Australia, Mr Denton has a very simplistic view on the relationship between religious faith, law and public morality. Basically he thinks religious people have no role in the public square when it comes to contested moral issues and that it is only faith and not reason that informs the religious person's view of law and public morality. It's this insidious view 'hidden inside our democracy' which is contributing to us becoming a less caring society particularly when it comes to those who are 'other', those who are outsiders, those who are on the margins, and those who are weak and vulnerable.

That's why I am delighted to be here under the auspices of the University of Notre Dame Law Students' Society to deliver your fourth annual social justice lecture. I urge you never to lose sight of the fact that though the Catholic Church might often be wrong or found wanting, society is always the richer for having public discourse which permits and encourages religious views, including the principles of Catholic social teaching, to help inform the discussion, the debate and the outcome of public policy issues which impact particularly upon the poor and the marginalised. Never has that been more the case than when we come to consider Australia's treatment of asylum seekers — my topic for this evening.

In April, when Papua New Guinea's highest court struck down the detention regime for asylum seekers and proven refugees shipped from Australia and detained on Manus Island, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said, 'We cannot be misty-eyed about this. We have to be very clear and determined in our national purpose ... We must have secure borders and we do and we will, and they will remain so, as long as I am the Prime Minister of this country.' Last month at the United Nations he told the world's leaders: 'We need to see the world clear eyed as it is, not as we would like it to be, or as we fondly imagine it once was. Secure borders are essential. Porous borders drain away public support for multiculturalism, for immigration, for aid to refugees. Most importantly, the only way to stop the scourge of people smuggling is to deprive the people smugglers of their product and secure borders do just that.' Just prior to his UN Address, he told the international media: 'Our policy on border protection is the best in the world'.

Even Mr Turnbull would need to concede that Australia's policy is unique and unrepeatable by other nations because it requires that you be an island nation continent without asylum seekers in direct flight from persecution in the countries next door and that you have access to a couple of other neighbouring island nations which are so indigent that they will receive cash payments in exchange for warehousing asylum seekers and proven refugees for over three years, and perhaps even indefinitely. The policy over which Mr Turnbull presides is not world best practice. It's a disgrace, and will remain so until the proven refugees on Manus Island and Nauru are permanently resettled.

While listening to the self-satisfied, self-congratulatory observations of our Australian representatives at the UN Summit on Refugees and Migrants and at the Obama summit, I asked myself what Messrs Turnbull and Dutton have done to provide a humane solution for the proven refugees on Nauru and Manus Island, given that after three years the Abbott and Turnbull governments have not resettled one proven refugee. You will recall that the MOU with Nauru was signed by the Rudd Government just prior to the 2013 election and that Richard Marles, the Labor shadow minister, told us during the recent election that the expectation was that the whole thing would be done and dusted within a year.

Three years of wanton inhumane treatment has been meted out to these people, and now those responsible have the hide to proclaim to other nations that our border protection system is 'the best in the world'. The MOU with Nauru provides:

Outcomes for persons Transferred to Nauru

12. The Republic of Nauru undertakes to enable Transferees who it determines are in need of international protection to settle in Nauru, subject to agreement between Participants on arrangements and numbers. This agreement between Participants on arrangements and numbers will be subject to review on a 12 monthly basis through the Australia-Nauru Ministerial Forum.

13. The Commonwealth of Australia will assist the Republic of Nauru to settle in a third safe country all Transferees who the Republic of Nauru determines are in need of international protection, other than those who are permitted to settle in Nauru pursuant to Clause 12.

14. The Commonwealth of Australia will assist the Republic of Nauru to remove Transferees who are found not to be in need of international protection to their countries of origin or to third countries in respect of which they have a right to enter and reside.

Timing

15. Subject to Clause 12, the Commonwealth of Australia will make all efforts to ensure that all Transferees depart the Republic of Nauru within as short a time as is reasonably necessary for the implementation of this MOU, bearing in mind the objectives set out in the Preamble and Clause 1.

The hypocrisy of it all is breath-taking. The numbers we have to deal with are pitifully small compared with those confronting other societies to which Turnbull and Dutton are proclaiming their achievements. No other country maintains a caseload of proven refugees living in hopeless conditions simply so as to 'send a message' and to retain the artifice that the house of cards 'stops the boats'. Now that they have returned from New York, Turnbull and Dutton should have the decency to agree that all proven refugees on Manus Island and Nauru who cannot be resettled elsewhere by the end of the year are to be resettled promptly in Australia (after the 3 year delay), and Bill Shorten and the Greens should agree without trying to make any political capital over the government's necessary change of policy.

Next week when Parliament resumes, it would be good to hear our prime minister give an account of his stewardship by giving us the details of the last three years' annual reviews by the Australia-Nauru Ministerial Forum setting out the numbers of proven refugees agreed each year for permanent settlement in Nauru. It will then be a simple mathematical exercise to determine the number of remaining proven refugees who are to be resettled in safe third countries with assistance from Australia.

Then, in light of Mr Turnbull's recent decision to decline New Zealand's repeated offer to resettle some of the caseload there (in stark contrast to what John Howard did with Tampa), he might tell the Parliament in what sense his government has 'made all efforts to ensure that all Transferees depart the Republic of Nauru within as short a time as is reasonably necessary for the implementation of this MOU'. Absent such an account to the parliament and people of Australia, this MOU is simply being used as an artifice to dump proven refugees in Nauru, in the hope that they will just go away or go back to face their persecutors.

The clear eyed and misty eyed popes on the world stage

I dare to suggest that recent popes have given more thought to the morality of this issue than have recent prime ministers. The present pontiff, Francis, has given extraordinary leadership. They have been more ready than our political leaders to admit the moral complexity of the issue. Pope Francis's first pastoral visit outside Rome was to Lampedusa, a small Italian island in the Mediterranean. Lampedusa continues to be a beacon for asylum seekers fleeing desperate situations in Africa seeking admission into the EU. Fleeing desperate situations in failed states like Somalia, asylum seekers transit another failed state Libya before boarding flimsy rafts in the Mediterranean Sea. It would be inhumane to send people back to Libya. Even before the recent outflow from Syria via Turkey, Lampedusa has been a lightning rod for European concerns about the security of borders in an increasingly globalised world where people as well as capital flow across porous borders. That's why Pope Francis went there. At Lampedusa on 8 July 2013, Pope Francis said:

'Where is your brother?' Who is responsible for this blood? In Spanish literature we have a comedy of Lope de Vega which tells how the people of the town of Fuente Ovejuna kill their governor because he is a tyrant. They do it in such a way that no one knows who the actual killer is. So when the royal judge asks: 'Who killed the governor?', they all reply: 'Fuente Ovejuna, sir'. Everybody and nobody! Today too, the question has to be asked: Who is responsible for the blood of these brothers and sisters of ours? Nobody! That is our answer: It isn't me; I don't have anything to do with it; it must be someone else, but certainly not me. Yet God is asking each of us: 'Where is the blood of your brother which cries out to me?' Today no one in our world feels responsible; we have lost a sense of responsibility for our brothers and sisters. We have fallen into the hypocrisy of the priest and the levite whom Jesus described in the parable of the Good Samaritan: we see our brother half dead on the side of the road, and perhaps we say to ourselves: 'poor soul ... !', and then go on our way. It's not our responsibility, and with that we feel reassured, assuaged. The culture of comfort, which makes us think only of ourselves, makes us insensitive to the cries of other people, makes us live in soap bubbles which, however lovely, are insubstantial; they offer a fleeting and empty illusion which results in indifference to others; indeed, it even leads to the globalisation of indifference. In this globalized world, we have fallen into globalized indifference. We have become used to the suffering of others: it doesn't affect me; it doesn't concern me; it's none of my business!

Here we can think of Manzoni's character — 'the Unnamed'. The globalisation of indifference makes us all 'unnamed', responsible, yet nameless and faceless.

He makes the political personal; he casts the responsibility for the one in need on to the other who has the capacity to help directly as an individual, or indirectly as a citizen or legislator in a nation state able to open borders to the asylum seeker.

Another key insight into Francis was revealed when he addressed the US Congress in September 2015. He commenced: 'I am most grateful for your invitation to address this Joint Session of Congress in "the land of the free and the home of the brave". I would like to think that the reason for this is that I too am a son of this great continent, from which we have all received so much and toward which we share a common responsibility.' He went in their door but only in order to bring them straight out his. He allowed his listeners to be lulled into the proud contentment of national identity before then turning the tables and establishing their shared geographic identity, underpinning their shared responsibility for the stranger and the one in need south of the Mexican border.

Though he does not write with the same clarity as his predecessors Benedict and John Paul, Francis has a more direct way of calling his listeners and interlocutors to account — to an account of conscience. He is a great one for the symbolic action in solidarity and for the folksy one-liner highlighting human interdependence.

When it comes to issues of migration, asylum and border protection, not even his predecessors can claim to have offered intellectual clarity about the limits of national responsibility. And, pace Malcolm Turnbull and Peter Dutton, that's because there is none. Francis has broken through some of the intellectual uncertainty with symbolic actions which speak to those on both sides of national borders, calling all to give an account of themselves — first with his visit to Lampedusa, then with his visit to the US-Mexico border, and then with his visit to Lesbos in company with the two patriarchs, His Holiness Bartholomew, Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, and His Beatitude Ieronymos, Archbishop of Athens and all Greece.

Not even John Paul II in his vast corpus of social encyclicals had much to say about the right to migrate. In his great human rights encyclical Pacem in Terris published in 1963, Pope John XXIII had spoken of the right to emigrate and immigrate. Harking back to Pius XII's 1952 Christmas message, John said:

Again, every human being has the right to freedom of movement and of residence within the confines of his own State. When there are just reasons in favor of it, he must be permitted to emigrate to other countries and take up residence there. The fact that he is a citizen of a particular State does not deprive him of membership in the human family, nor of citizenship in that universal society, the common, world-wide fellowship of men.

John went on to give his 'public approval and commendation to every undertaking, founded on the principles of human solidarity or of Christian charity, which aims at relieving the distress of those who are compelled to emigrate from their own country to another.'

The UN's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which was open for ratification just three years after Pacem in Terris made no mention of a right to emigrate. It confined its attention to the right to leave any country and the right to enter one's own country. The Covenant added nothing of substance to the 1951 Refugees Convention which did not accord asylum seekers the right to enter any country other than their own. That Convention simply ensured that any asylum seeker in direct flight from persecution was not to be disadvantaged for their illegal entry to a country were they successfully to gain entry, and that they were not to be refouled to their country of persecution prior to the determination of their refugee claim once they had gained entry, even if it be illegal.

Recent popes have wrestled with what constitutes a just reason for emigrating to another country not one's own and taking up residence there. While focusing on the individual and their human rights, the popes also give attention to the family, the community and the nation which are the privileged loci within which the individual enjoying their human rights is able to achieve their full human flourishing. Thus the national interest is important to evaluate, especially when considering culture, religious freedom and economic prosperity. Though affirming the universal destination of goods and the universal brotherhood of man, the popes have tended to espouse national borders as necessary, contingent preconditions for full human flourishing. But in recent years, they have drawn attention to the particular responsibility which those behind secure national borders owe to those presenting at their borders seeking asylum in direct flight from persecution.

The popes know that the principles of Catholic social teaching they develop need to apply to a broad range of national borders. Some countries are net migration countries, others are not. Some net migration countries can control their borders being able to allocate places for business, family reunion and humanitarian migration. There is no simple moral formula for determining what proportion of places should go to which categories, or for determining what percentage of national population growth should be accountable to migration rather than natural increase. Some migrant cohorts come from cultures and religious backgrounds similar to those in the nation state. Others are very diverse. Some countries insist that all workers be paid the same wages; others permit migrant workers from poor countries to be paid less, given that they will still be receiving much more than they would back home.

Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis have all addressed the United Nations. The last three popes have also addressed national legislatures. These addresses give them the opportunity to reflect on the role of civil law in fostering human flourishing. Benedict gave a particularly insightful address when he returned to his home country Germany and addressed the Bundestag. He asked the legislators, 'How do we recognise what is right?' He answered, 'In history, systems of law have almost always been based on religion: decisions regarding what was to be lawful among men were taken with reference to the divinity. Unlike other great religions, Christianity has never proposed a revealed law to the State and to society, that is to say a juridical order derived from revelation. Instead, it has pointed to nature and reason as the true sources of law — and to the harmony of objective and subjective reason, which naturally presupposes that both spheres are rooted in the creative reason of God.' Conceding the declining influence of Christianity, he nonetheless claimed that the encounter between Christianity and legislators in the west culminated after World War II in the commitment to 'inviolable and inalienable human rights as the foundation of every human community, and of peace and justice in the world'.

All three recent popes have published an annual message for World Migration Day in addition to their Annual Message on the World Day of Peace. These addresses have required them to develop a fairly nuanced Catholic Social Teaching on migration. In 2001, Pope John Paul II warned against any indiscriminate licence to migrate and also against highly developed countries becoming too exclusive. He said:

These rights are concretely employed in the concept of universal common good, which includes the whole family of peoples, beyond every nationalistic egoism. The right to emigrate must be considered in this context. The Church recognises this right in every human person, in its dual aspect of the possibility to leave one's country and the possibility to enter another country to look for better conditions of life. Certainly, the exercise of such a right is to be regulated, because practicing it indiscriminately may do harm and be detrimental to the common good of the community that receives the migrant. Before the manifold interests that are interwoven side by side with the laws of the individual countries, it is necessary to have international norms that are capable of regulating everyone's rights, so as to prevent unilateral decisions that are harmful to the weakest.

In this regard, in the Message for Migrants' Day of 1993, I called to mind that although it is true that highly developed countries are not always able to assimilate all those who emigrate, nonetheless it should be pointed out that the criterion for determining the level that can be sustained cannot be based solely on protecting their own prosperity, while failing to take into consideration the needs of persons who are tragically forced to ask for hospitality.

In his World Day of Peace Message for 2001, John Paul II said, 'The challenge is to combine the welcome due to every human being, especially when in need, with a reckoning of what is necessary for both the local inhabitants and the new arrivals to live a dignified and peaceful life.' John Paul II revisited the issue three years later in his 2004 Message for World Migration Day when he said:

As regards immigrants and refugees, building conditions of peace means in practice being seriously committed to safeguarding first of all the right not to emigrate, that is, the right to live in peace and dignity in one's own country. By means of a farsighted local and national administration, more equitable trade and supportive international cooperation, it is possible for every country to guarantee its own population, in addition to freedom of expression and movement, the possibility to satisfy basic needs such as food, health care, work, housing and education; the frustration of these needs forces many into a position where their only option is to emigrate.

Equally, the right to emigrate exists. This right, Bl. John XXIII recalls in the Encyclical Mater et Magistra, is based on the universal destination of the goods of this world (cf. nn. 30 and 33). It is obviously the task of Governments to regulate the migratory flows with full respect for the dignity of the persons and for their families' needs, mindful of the requirements of the host societies. In this regard, international Agreements already exist to protect would-be emigrants, as well as those who seek refuge or political asylum in another country. There is always room to improve these agreements.

In his 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritate, Pope Benedict XVI spoke about the 'striking phenomenon' of migration (including the plight of lowly paid foreign workers) — 'a social phenomenon of epoch-making proportions that requires bold, forward-looking policies of international co-operation'. He highlighted 'the sheer numbers of people involved, the social, economic, political, cultural and religious problems it raises, and the dramatic challenges it poses to nations and the international community'. He thought migration policies 'should set out from close collaboration between the migrants' countries of origin and their countries of destination; they should be accompanied by adequate international norms able to coordinate different legislative systems with a view to safeguarding the needs and rights of individual migrants and their families, and at the same time, those of the host countries'.

Revisiting John Paul's 2001 Migration Day statement in 2011, Benedict added the observation: 'States have the right to regulate migration flows and to defend their own frontiers, always guaranteeing the respect due to the dignity of each and every human person. Immigrants, moreover, have the duty to integrate into the host Country, respecting its laws and its national identity.'

Addressing the European Parliament in 2014, Pope Francis said:

Likewise, there needs to be a united response to the question of migration. We cannot allow the Mediterranean to become a vast cemetery! The boats landing daily on the shores of Europe are filled with men and women who need acceptance and assistance. The absence of mutual support within the European Union runs the risk of encouraging particularistic solutions to the problem, solutions which fail to take into account the human dignity of immigrants, and thus contribute to slave labour and continuing social tensions. Europe will be able to confront the problems associated with immigration only if it is capable of clearly asserting its own cultural identity and enacting adequate legislation to protect the rights of European citizens and to ensure the acceptance of immigrants. Only if it is capable of adopting fair, courageous and realistic policies which can assist the countries of origin in their own social and political development and in their efforts to resolve internal conflicts — the principal cause of this phenomenon — rather than adopting policies motivated by self-interest, which increase and feed such conflicts. We need to take action against the causes and not only the effects.

In his Message for the 2016 World Day for Migrants and Refugees, Francis made the observation:

The presence of migrants and refugees seriously challenges the various societies which accept them. Those societies are faced with new situations which could create serious hardship unless they are suitably motivated, managed and regulated. How can we ensure that integration will become mutual enrichment, open up positive perspectives to communities, and prevent the danger of discrimination, racism, extreme nationalism or xenophobia?

When he visited Lesbos in April 2016, he commenced with this concession: 'The worries expressed by institutions and people, both in Greece and in other European countries, are understandable and legitimate.' He, like his predecessors, takes seriously the nation state's entitlement to maintain secure borders so as to enhance the prospects of full human flourishing for citizens seeking a full cultural, religious and economic life in harmony with their fellow citizens. But in a world with 60 million people displaced and seeking asylum, that is not the full picture, and thus not the entirety of Catholic social teaching on the right to migrate. Francis had already demonstrated in his address to the European Parliament that he understands the pressures on the modern nation state when dealing with migration flows. Thus his considered decision to go to Lesbos in company with the two patriarchs, not on a political mission but with a humanitarian purpose, drawing attention to the plight of those on the borders of life. Having acknowledged the understandable and legitimate concerns of those wanting to maintain secure borders, Francis went on to say:

We must never forget, however, that migrants, rather than simply being a statistic, are first of all persons who have faces, names and individual stories. Europe is the homeland of human rights, and whoever sets foot on European soil ought to sense this, and thus become more aware of the duty to respect and defend those rights. Unfortunately, some, including many infants, could not even make it to these shores: they died at sea, victims of unsafe and inhumane means of transport, prey to unscrupulous thugs.

He then took 12 Muslim asylum seekers with him on his plane back to the Vatican. He made no pretence to tell European legislators how many asylum seekers they should accept, or how they should maintain the integrity of their borders. He and the patriarchs issued a joint declaration espousing uncontroversial demands such as the need to address root causes of migration flows, and the need to do more co-operatively to help those in desperate need:

[W]e call upon all political leaders to employ every means to ensure that individuals and communities, including Christians, remain in their homelands and enjoy the fundamental right to live in peace and security. A broader international consensus and an assistance programme are urgently needed to uphold the rule of law, to defend fundamental human rights in this unsustainable situation, to protect minorities, to combat human trafficking and smuggling, to eliminate unsafe routes, such as those through the Aegean and the entire Mediterranean, and to develop safe resettlement procedures.

Catholic social teaching on the right to migrate provides us with principles which are useful in fostering a culture of engagement, seeking partial, more acceptable answers to insuperable problems. Pope Francis's symbolic actions, placing himself and his office deliberately at the borders of life, provide us with the incentive to develop a culture of encounter, animated to assist the asylum seeker who is other but who is present and centre stage in the pope's reflections. Francis, like his predecessors, is not proposing a borderless world but he is challenging all persons to display mercy and compassion across borders, and in dimensions they have dared not contemplate or attempt in the past. He is not falling into the trap which John Finnis, the Oxford don and longtime member of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and of the International Theological Commission, describes as clerical overreach producing 'a rhetorical drift towards equating the borderless, cosmopolitan Church — in which there is "neither Jew nor Greek" but all are equally and everywhere at home — with political community envisaged as if it likewise ought to be substantially borderless even if that resulted (but such consequences are not articulated even for consideration) in the annulling of national cultures, constitutions, and peoples.'

We are blessed that our recent popes have continued to espouse the basic human rights of the poor migrant worker and of the hapless asylum seeker while always maintaining a commitment to the political community's preconditions for contributing to the full human flourishing of those privileged to enjoy citizenship especially in those nation states which boast the rule of law, economic resilience, and secure religious and cultural identities. The visits by Francis to Lampedusa, the US-Mexico border and Lesbos provide Australians of good will with the incentive and inspiration to revisit Catholic social teaching on migration, recommitting ourselves to the provision of asylum to those deserving it in our region while maintaining national security so that all who call Australia home might enjoy the benefits of their full human flourishing, including the capacity to help the neighbour in need. When answering who is our neighbour, we will then be more ready to respond to Jesus' answer in the mode of another question, 'Which of these three, do you think, proved neighbour to the man who fell among the robbers?' The mature political community is the one which enables its members to respond, 'The one who showed mercy on him' and to 'go and do likewise'. (Lk 10:36-7) We are blessed to have Pope Francis appearing at the borders of life inviting us to respond with mercy. How would we feel if he were to turn up at Christmas Island, Nauru or Manus Island? And more to the point, what would we do in response to his challenge to us — a challenge grounded in the nuances of Catholic social teaching on the right to migrate?

Getting Australians to open their eyes

In August, I joined Robert Manne, Tim Costello and John Menadue in calling for an end to the limbo imposed on proven refugees on Nauru and Manus Island. I think this can be done while keeping the boats stopped. I think it ought be done while we work out how best to stop the boats. Warehousing proven refugees for years on end is not an option. I concede that the moral calculus of Australia's present policy dilemma is very different from the case of persons in direct flight from persecution IN Indonesia. If there were people fleeing persecution IN Indonesia, we would be obliged to receive them, whether or not they came with visas, whether they arrived by boat or plane. As those coming are not fleeing persecution IN Indonesia, we are entitled to deny them entry and to return them safely to Indonesia provided we have the assurance that the Indonesians will not refoule them to their home country where they would encounter persecution or to another country where they might encounter the risk of return to persecution, and provided there are arrangements in place in Indonesia for the processing of refugee claims and for security while claims are processed. These provisos cannot be satisfactorily in place unless we have a transparent bilateral agreement with Indonesia, a regional agreement with transit countries, and appropriate funding commitments to UNHCR and IOM for their operations in Indonesia. If these provisos were in place, I would accept Australia's bipartisan commitment in the Parliament to 'stopping the boats'. For the moment, I am still uneasy about the lack of transparency in the way our defence personnel are called upon to turn back boats. For the moment, I accept the unalterable political imperative that the boats stay stopped. But if we were to put these provisos in place, I could then accept without strong moral objection the stopping of the boats.

Appearing on the ABC 7.30 program after The Guardian's release of 2000 incident reports from Nauru, Peter Dutton, the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, told presenter Leigh Sales, 'I would like to get people off Nauru tomorrow but I have got to do it in such a way that we don't restart boats.' He went on to say, 'We have had discussions with a number of other countries, but what we're not going to do is enter into an arrangement that sends a green light to people smugglers.' Dutton appreciates that Nauru and Manus Island are ticking time bombs.

During the election campaign, Malcolm Turnbull said that we could not be misty eyed about the situation on these islands, a situation of Australia's making and a situation funded recurrently with the Australian cheque book. Now that the election is over, neither our politicians nor their strategic advisers can afford wilfully to close their eyes to the situation. The majority of asylum seekers on Nauru and Manus Island have now been proved to be refugees. They are not going to accept cheques to go back home and face renewed persecution. That's why they fled in the first place. Most of these people have had their lives on hold, in appalling circumstances, for over three years. It's time to act. Ongoing inaction will send a green light to desperate people to do desperate things.

While respecting those refugee advocates and their supporters who cannot countenance stopping the boats coming from Indonesia, I think it is time to see if we can design a way of getting the asylum seekers off Nauru and Manus Island 'in such a way that we don't restart boats', ensuring that we continue to send a red light to people smugglers in Java. The precedent is the Howard government's successful plan to empty the Nauru and Manus Island processing centres while winding back its original Pacific Solution, ensuring the boats stayed stopped.

To set a new direction, we have first to put aside the undesirable and unworkable aspects of the present policy settings. Are not our military and intelligence services (in cooperation with Indonesian officials) sufficiently on the job that they can stop people smugglers in their tracks, stopping boats from being filled, stopping boats from setting out and turning back any that set out, regardless of whether proven refugees on Nauru and Manus Island are resettled elsewhere (even ultimately in Australia)?

The suggestion that those camps need to remain filled in order to send a message to people smugglers so that the boats will stay stopped is not only morally unacceptable; it is strategically questionable. Those proven to be refugees should be resettled as quickly as practicable, and that includes taking up New Zealand's offer of 150 places a year — just as John Howard did when he accepted New Zealand's offer to take 131 from the Tampa.

In 2012, Angus Houston's expert panel proposed a resurrected Pacific solution to the Gillard government for two purposes only. The panel saw it as a temporary circuit breaker until the boats could be stopped and turned back lawfully and safely. Houston's expert panel did not propose it as a permanent precondition for being able to stop boats and turn them back. The panel was very aware of the evidence given to parliament the previous year by Andrew Metcalfe, long time secretary of the Immigration Department:

Our view is not simply that the Nauru option would not work but that the combination of circumstances that existed at the end of 2001 could not be repeated with success. That is a view that we held for some time — and it is of course not just a view of my department; it is the collective view of agencies involved in providing advice in this area.

Secondly, the expert panel saw the maintenance of the offshore processing centres once the boats had stopped as a necessary part of the jigsaw in designing a regional solution for the protection, processing and resettlement of refugees in South East Asia. Given that there has been no continuing flow of irregular maritime arrivals (IMAs), Houston saw no warrant for keeping proven refugees on Nauru or Manus Island for years on end, without any end in prospect. The Houston Panel stated:

The Panel's view is that, in the short term, the establishment of processing facilities in Nauru as soon as practical is a necessary circuit breaker to the current surge in irregular migration to Australia. It is also an important measure to diminish the prospect of further loss of life at sea. Over time, further development of such facilities in Nauru would need to take account of the ongoing flow of IMAs to Australia and progress towards the goal of an integrated regional framework for the processing of asylum claims.

Given that there has been no 'ongoing flow of IMAs to Australia', the only case for maintaining processing facilities on Nauru and Manus Island, in line with the Houston recommendations, would be as part of 'an integrated regional framework for the processing of asylum claims'. To date, the Abbott and Turnbull governments have done NOTHING to establish that framework. Nauru and Manus Island no longer perform any credible, morally coherent, or useful task in securing Australia's borders. Even talk of sending signals is misplaced. The main signal is being sent to Australian voters, not to asylum seekers waiting in Java whose attempts to commission people smugglers have been thwarted by Indonesian officials and Australian intelligence, and whose boats would be turned back in any event.

On 11 August 2016, Dutton said 'we have had discussions with a number of other countries' but then went on to say, 'I think the situation is that people have paid people smugglers for a migration outcome. They want to come to Australia, they don't want to go to New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Malaysia, anywhere else.' It's time for Turnbull, Shorten and Di Natale to agree on a timetable. If the government is unable to resettle the proven refugees elsewhere in countries like New Zealand and Canada by the end of the year, the refugees should be resettled in Australia. If there are still asylum seekers awaiting determination of their claims by the end of the year, they should be brought to Christmas Island for processing. To keep them any longer on Nauru and Manus Island is to tempt fate adverse to their interests, adverse to the national interest of PNG and Nauru, and adverse to Australia's international standing and sense of ourselves.

Dutton's status quo cannot work much longer, and he must know that. The stakes are very high, and not just for those proven refugees we continue to punish so publicly and so unapologetically pretending that we are treating them decently. Turnbull and Dutton have a mandate to stop the boats. They have no mandate to make these people suffer more, in our name, for no appreciable benefit to anybody.

To keep them on hold any longer in such circumstances will be to send a green light to desperate, trapped people doing desperate things beyond the control of the governments and service providers paid with Australian tax dollars to keep them out of sight and out of mind. It's time for our politicians to agree to defuse the ticking time bombs of Nauru and Manus Island. I agree with Mr Turnbull's claim to the UN that 'secure borders are essential. Porous borders drain away public support for multiculturalism, for immigration, for aid to refugees'. He was right to highlight the three pillars of any effective and acceptable policy: strong border controls; a compassionate humanitarian commitment to substantial resettlement programs and support for those countries hosting large numbers of refugees; and effective international and regional co-operation.

Mr Turnbull was right to insist, 'These three pillars are inherently interlinked. They cannot and do not work in isolation.' But furthermore, they cannot work if their operation is premised on warehousing proven refugees on remote Pacific islands indefinitely so as to send a message when the warehousing is not needed to stop the boats. Even if such warehousing were a precondition for stopping boats (which it's not), it would still be completely morally unacceptable. The task and challenge for Notre Dame law graduates is to ensure in future that such a morally repugnant policy is rendered both unlawful and politically unacceptable. I say this as a Catholic; I say this as an Australian citizen. I daresay Mr Andrew Denton on this occasion would not question my right to speak in these terms. That may be only because he agrees with my conclusions. But I would hope that it might also be because, on second thoughts, he applauds my right to bring my religious sensibilities to bear on this and other vexed moral and political questions of the day. Some humanitarian disasters in our world are so bad and so intractable that we have no option than to be both clear eyed in our thinking and misty eyed in our compassion, clear eyed in calculating our interdependence, misty eyed in pledging our solidarity. The purported certainty of Messrs Turnbull and Dutton shutting the door on the proven refugees on Manus Island and Nauru is not the result of clear eyed thinking but of blind political opportunism. It's time to allow those refugees who are our responsibility to walk free.