The following text is from Frank Brennan's Leading the Way Seminar for the National Disability Service, Hilton, Sydney, 9 February 2014

I was a participant at Kevin Rudd's 2020 summit. But I was not part of any stream that produced a nation changing outcome. After the summit, I was asked to chair the National Human Rights Consultation which investigated one of the big ideas from the summit — a national Human Rights Act. But the changes which followed were much more modest than that. So I pay tribute to Bruce Bonyhady and John Della Bosca who took forward one of the few 2020 Summit ideas which was really big, really new, likely to make a huge difference in the lives of Australians, and now given a chance of actual realisation. I commend them and politicians like Bill Shorten and Jenny Macklin for seeing through a commitment to replacing a disability system based on welfare with one based on insurance, investment and individualised funding. I also commend those like Mitch Fifield in the Coalition who have worked to ensure a bipartisan approach to this issue even during the dreadful days of the last toxic Parliament. On 16 May 2013, Fifield told the Senate: 'The Coalition has supported the establishment of the NDIS every step of the way. We want it to be a success.' It is heartening that the Abbott government has maintained this commitment.

The NDIS and the market

If it succeeds, the NDIS will provide comprehensive insurance (an individualised support package) for 460,000 of the 4 million Australians suffering some form of disability. Bruce Bonyhady has long claimed that the political appeal of an NDIS lies in the fact that any of us or any member of our family could in the future be in need of future assistance from such a scheme. As he says, 'The NDIS is for all Australians because none of us know when we may acquire a disability ourselves, or have a family member with disability.' This is the first real challenge in times of political change and in times of financial constraint. The average punter who knows little about these issues wonders how the scheme can be marketed as being for all Australians while at the same time providing direct benefits and coverage only to 12 per cent of those suffering disability. Australians will maintain faith in the NDIS only if they are convinced that the other 88 per cent are not being left behind, and if they are assured that the cut-offs for eligibility are coherent, comprehensible, fair and transparent.

The second big challenge for those of you administering the scheme is, as Bruce says, 'to take a firm and fair stand in order to ensure that the boundaries of eligibility and reasonable and necessary benefits which are contained in the regulations are maintained and not widened in ways which would undermine the Scheme's sustainability.' The scheme will need to be firm but fair.

The third challenge is to ensure that governments and providers 'do not shift costs which should be part of mainstream services onto the NDIS'. Cash strapped States are sure to invoke the mantra that some housing, transport and other services should be provided on a user pays basis for those eligible for an NDIS package.

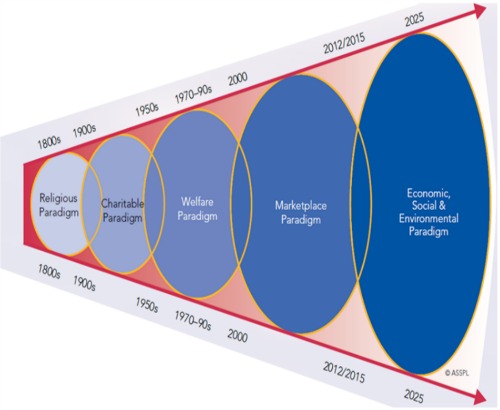

The National Disability Insurance Agency 'will need to take an active interest in ensuring that markets are competitive, so that the viability of the scheme is not undermined by price inflation'. We live in a world of changing paradigms. In the past, we looked to churches, then to charities, then to the welfare arm of the state. Nowadays we are more likely to look to the market:

The new Abbott Government has appointed a Commission of Audit to ensure 'Government should do for people what they cannot do, or cannot do efficiently, for themselves, but no more.' This means that individuals will be left more dependent on the market and civil society, with government being a last resort for the provision of services. Ross Gittins in his Gittins' Gospel writes: 'Markets are undoubtedly an efficient way to conduct economic activity and they impose their own disciplines on their participants. The problem comes when markets are seen as a 'system' possessed of almost magical powers to never run off the rails and always to deliver satisfactory outcomes without government interference. There's no such thing as a 'free market' — all markets are regulated by governments to a greater or lesser extent. It's just that, over the past thirty years, the intellectual fashion swung heavily in the direction of minimising regulation. We dismantled a lot of the safety rails. And we had regulators who doubted the wisdom of regulation.'

He concludes: 'We seem to have encountered a spate of examples of dubious and dishonest behaviour by business people. The notion that 'market forces' would do more to punish such behaviour than encourage it is now seen to be laughably naïve. Much closer to the truth is that it's always been the power of norms of socially acceptable behaviour that has done most to protect us from exploitation in the absence of vigorous law enforcement. But such behavioural norms may have broken down in the face of all our celebration of commercial success and the exorbitant sums the leaders of industry are awarding themselves.'

The market for disability services will need to be underpinned with a strong and robust internal risk management framework. There will be an increasing number of for-profit operators in the sector. Hopefully the not-for-profit operators will make the necessary adaptations competing in the market and providing the ethos for the market to deliver services in a dignified, fair and transparent manner.

Some learnings from the National Human Rights Consultation

In seeking the views of the Australian public during the National Human Rights Consultation in 2009, we made use of new technologies, conducted community consultations and received tens of thousands of submissions. I ran a Facebook page. We hosted a blog and commissioned academics on opposite sides of the argument to steer the blog debate. We held three days of hearings which were broadcast on the new Australian Public Affairs Channel. During the course of our consultation, various groups ran campaigns for and against a Human Rights Act in the wake of Australia's ongoing exceptionalism, Australia being the only remaining country in the British common law tradition without some form of Human Rights Act. Groups like GetUp! and Amnesty International ran strong campaigns in favour of a Human Rights Act, accounting for 25,000 of the 35,000 submissions we received. My committee did not see itself as having the competence or authority to distinguish campaign generated submissions from other submissions. We simply decided to publish the figures and let people make their own assessments.

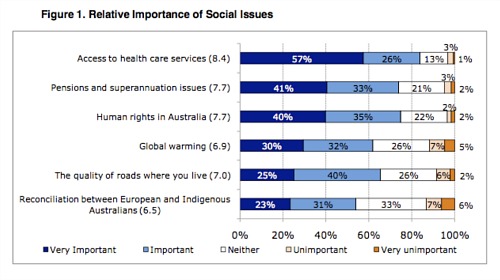

We engaged a social research firm, Colmar Brunton, to run focus groups and administer a detailed random telephone poll of 1200 persons. The poll highlighted the issues of greatest concern to the Australian community:

At community roundtables, participants were asked what prompted them to attend. Some civic-minded individuals simply wanted the opportunity to attend a genuine exercise in participative democracy; they wanted information just as much as they wanted to share their views. Many participants were people with grievances about government service delivery or particular government policies. Some had suffered at the hands of a government department or at least knew someone who had been adversely affected — a homeless person, an aged relative in care, a close family member with mental illness, or a neighbour with disabilities. Others were responding to invitations to involve themselves in campaigns that had been instigated when the Consultation was launched. Against the backdrop of these campaigns, the Committee heard from many people who claimed no legal or political expertise in relation to the desirability or otherwise of any particular law; they simply wanted to know that Australia would continue to play its role as a valued contributor to the international community while pragmatically dealing with problems at home.

Outside the capital cities and large urban centres, the community roundtables tended to focus on local concerns, and there was limited use of 'human rights' language. People were more comfortable talking about the fair go, wanting to know what constitutes fair service delivery for small populations in far-flung places. At Mintabie in outback South Australia, a quarter of the town's population turned out, upset by the recent closure of their health clinic. At Santa Teresa in the red centre, Aboriginal residents asked me how I would feel if the government required that I place a notice banning pornography on the front door of my house. They thought that was the equivalent of the government erecting the 'Prescribed Area' sign at the entrance to their community. In Charleville, western Queensland, the local doctor described the financial hardship endured by citizens who need to travel 600km by bus to Toowoomba for routine specialist care.

The Committee learnt that economic, social and cultural rights are important to the Australian community, and the way they are protected and promoted has a big impact on the lives of many. The most basic economic and social rights — the rights to the highest attainable standard of health, to housing and to education — matter most to Australians, and they matter most because they are the rights at greatest risk, especially for vulnerable groups in the community.

The community roundtables bore out the finding of Colmar Brunton Social Research's 15 focus groups that the community regards the following rights as unconditional and not to be limited:

- basic amenities — water, food, clothing and shelter

- essential health care

- equitable access to justice

- freedom of speech

- freedom of religious expression

- freedom from discrimination

- personal safety

- education

Many of the more detailed submissions presented to the Committee argued that all the rights detailed in the primary international instruments Australia has ratified without reservation should be protected and promoted. Most often mentioned were the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966, which, along with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, constitute the 'International Bill of Rights'.

Some submissions also included the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women 1979, the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment 1984, the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006.

Having ratified these seven important human rights treaties, Australia has voluntarily undertaken to protect and promote the rights listed in them. This was a tension for us in answering the first question. Many roundtable participants and submission makers spoke from their own experience, highlighting those rights most under threat for them or for those in their circle. Others provided us with a more theoretical approach, arguing that all Australia's international human rights obligations should be complied with.

True to what we heard from the grassroots, we singled out three key economic and social rights for immediate enhanced attention by the Australian Human Rights Commission — the rights to health, education, and housing. We thought that government departments should be attentive to the progressive realization of these rights, within the constraints of what is economically deliverable. However, in light of advice received from the Solicitor-General, we did not think the courts could have a role to play in the progressive realization of these rights.

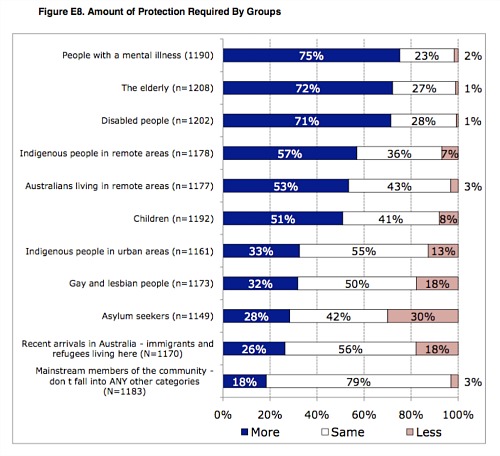

We recommended that the federal government operate on the assumption that, unless it has entered a formal reservation in relation to a particular right, any right listed in the seven international human rights treaties should be protected and promoted. There is enormous diversity in the community when it comes to understanding of rights protection. Though two thirds of those who participated in the random survey thought human rights were adequately protected in Australia, over 70 per cent identified three groups in the community whose rights were in need of greater protection.

The majority of those surveyed also saw a need for better protection of the human rights of those living in remote rural areas. The near division of the survey groups when it comes to the treatment of asylum seekers highlights why this issue recurs at Australian elections.

The philosophical basis of rights talk

When he was Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams gave an insightful address at the London School of Economics pointing out that rights and utility are the two concepts that resonate most readily in the public square today. But we need concepts to set limits on rights when they interfere with the common good or the public interest, or dare I say it, public morality — the concepts used by the UN when first formulating and limiting human rights 66 years ago. These concepts are no longer in vogue, at least under these titles. We also need concepts to set limits on utility when it interferes with the dignity of the most vulnerable and the liberty of the most despised in our community. Addressing the UN General Assembly to mark the anniversary of the UN Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR), Pope Benedict XVI said, 'This document was the outcome of a convergence of different religious and cultural traditions, all of them motivated by the common desire to place the human person at the heart of institutions, laws and the workings of society, and to consider the human person essential for the world of culture, religion and science...(T)he universality, indivisibility and interdependence of human rights all serve as guarantees safeguarding human dignity.' It would be a serious mistake to view the UNDHR stipulation and limitation of rights as a western Judaeo-Christian construct.

Mary Ann Glendon's A World Made New traces the remarkable contribution to that document by Eleanor Roosevelt and an international bevy of diplomats and academics whose backgrounds give the lie to the claim that any listing of human rights is a Western culturally biased catalogue of capitalist political aspirations. The Frenchman Rene Cassin, the Chilean Hernan Santa Cruz, the Christian Lebanese Adam Malik and the Chinese Confucian Peng-chun Chang were great contributors to this truly international undertaking. They consulted religious and philosophical greats such as Teilhard de Chardin and Mahatma Gandhi. Even Aldous Huxley made a contribution. It was the Jesuit palaeontologist Teilhard who counselled that the drafters should focus on 'man in society' rather than man as an individual. The drafters knew that any catalogue of rights would need to include words of limitation. The Canadian John Humphrey who was the Director of the UN secretariat servicing the drafting committee prepared a first draft of 48 articles. The Australian member of the drafting committee Colonel Hodgson wanted to know the draft's underlying philosophy. Humphrey refused to answer, replying 'that the draft was not based on any particular philosophy; it included rights recognised by various national constitutions and also a number of suggestions that had been made for an international bill of rights'. In his memoirs, Humphrey recounts: 'I wasn't going to tell him that insofar as it reflected the views of its author — who had in any event to remain anonymous — the draft attempted to combine humanitarian liberalism with social democracy.' It is fascinating to track the different ways in which the committee dealt with the delimitation of rights. Humphrey proposed that an individual's rights be limited 'by the rights of others and by the just requirements of the State and of the United Nations'.

Cassin proposed only one limitation on a person's rights: 'The rights of all persons are limited by the rights of others.' The 1947 Human Rights Commission draft stayed with Cassin's one stated limitation on rights: 'In the exercise of his rights, everyone is limited by the rights of others.' By the time the draft reached Geneva for the third meeting of the Human Rights Commission in May 1948, there was a much broader panoply of limitation on individual rights introduced, taking into account man's social character and re-introducing Humphrey's notion of just requirements of the state: 'In the exercise of his rights every one is limited by the rights of others and by the just requirements of the democratic state. The individual owes duties to society through which he is enabled to develop his spirit, mind and body in wider freedom.' The Commission then reconvened for its last session at Lake Success in June 1948. They approved the draft declaration 12-0.

Glendon notes: 'Pavlov, the Ukraine's Klekovkin, and Byelorussia's Stepanenko, in line with instructions issued before the meeting had begun, abstained and filed a minority report.' The Commission moved the words of limitation to the end of the draft and married the limitation to a statement about duties. Article 27 (which ultimately became Article 29) provided:

Everyone has duties to the community which enables him freely to develop his personality.

In the exercise of his rights, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are necessary to secure due recognition and respect for the rights of others and the requirements of morality, public order and general welfare in a democratic society.

So here in the heart of the modern world's most espoused declaration of human rights came an acknowledgment that we all have duties and not just rights, duties to the community which, perhaps counter-intuitively, enable us to develop our personalities. I doubt that phrase was coined by Eleanor Roosevelt. At the Commission, it was said that 'morality' and 'public order' were 'particularly necessary for the French text, since in English, 'general welfare' included both morality and public order'. At one stage it was suggested that the term 'public order' was too broad, permitting the grossest breach of human rights by those committing arbitrary acts and crimes in the name of maintaining public order. The commission considered the substitution of 'security for all' for 'public order', similar to the 28th article of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, but decided to stay with the more jurisprudentially certain European term 'public order'. But also we have the acknowledgment that individual rights might be limited not just for the preservation of public order and for the general welfare of persons in a democratic society, but also for morality — presumably to maintain, support, enhance or develop morality in a democratic society. Sixty years later, these words of limitation might not sit with us so readily.

The draft then went from the Human Rights Commission to the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly. The Committee convened more than 80 meetings to debate the declaration which it renamed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights rather than International Declaration of Human Rights. The limitation clause was considered during three of those meetings. The limitation clause was further amended so that the final Article 29 now reads:

Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

These rights and freedoms can in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Though there was much discussion of amendments to omit references to 'morality' and 'public order', the Third Committee decided to retain these terms as to delete the mention of them 'would be to base all limitations of the rights granted in the declaration on the requirements of general welfare in a democratic society and consequently to make them subject to the interpretation of the concept of democracy, on which there was the widest possible divergence of views.' As amended, this article was carried by 41 votes to none, with one abstention. The General Assembly then voted to adopt the universal declaration with 48 in favour, 8 abstentions and none opposed.

The Rudd and Gillard governments followed the UK, Ireland and New Zealand with a commitment to social inclusion giving all Australians the opportunity to:

secure a job;

access services;

connect with family, friends, work and their local community;

deal with crises; and

have their voices heard.

It may be in this grey area between rights and utility that social inclusion has work to do — work that was previously distributed amongst concepts such as human dignity, the common good, the public interest and public morality. Individuals and community groups living under law in the State are entitled equally to connect with their local community, to deal with crises in religiously and culturally appropriate ways, and to have their voices heard.

In the legal academy there continues to be a great evangelical fervour for bills of rights. This fervour manifests itself in florid espousals of the virtues of weak statutory bills of rights together with the assurance that one need not be afraid because such bills do not really change anything. Those of us with a pragmatic, evidentiary approach to the question are well positioned given that two of Australia's nine jurisdictions (Victoria and the ACT) have enacted such bills of rights with the double assurance that nothing has really changed and that things can now only get better. It will be interesting to hear an assessment of the socially inclusionary benefits of a bill of rights which provides lawyers and judges with greater access to the realm of policy and service delivery.

Article 4 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities provides: 'With regard to economic, social and cultural rights, each State Party undertakes to take measures to the maximum of its available resources and, where needed, within the framework of international cooperation, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of these rights, without prejudice to those obligations contained in the present Convention that are immediately applicable according to international law.' So we must always have an eye to what resources are available when discussing the rights to housing, health, education, and employment. We need to concede that these rights, unlike civil and political rights, are susceptible to progressive realization in the polity.

The limits of rights discourse

Once we investigate much of the contemporary discussion about human rights, we find that often the intended recipients of rights do not include all human beings but only those with certain capacities or those who share sufficient common attributes with the decision makers. It is always at the edges that there is real work for human rights discourse to do. Speaking at the London School of Economics on 'Religious Faith and Human Rights', Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury has boldly and correctly asserted:

The question of foundations for the discourse of non-negotiable rights is not one that lends itself to simple resolution in secular terms; so it is not at all odd if diverse ways of framing this question in religious terms flourish so persistently. The uncomfortable truth is that a purely secular account of human rights is always going to be problematic if it attempts to establish a language of rights as a supreme and non-contestable governing concept in ethics.

No one should pretend that the discourse about universal ethics and inalienable rights has a firmer foundation than it actually has. Williams concluded his lecture with this observation:

As in other areas of political or social thinking, theology is one of those elements that continues to pose questions about the legitimacy of what is said and what is done in society, about the foundations of law itself. The secularist way may not have an answer and may not be convinced that the religious believer has an answer that can be generally accepted; but our discussion of social and political ethics will be a great deal poorer if we cannot acknowledge the force of the question.

Once we abandon any religious sense that the human person is created in the image and likeness of God and that God has commissioned even the powerful to act justly, love tenderly and walk humbly, it may be very difficult to maintain a human rights commitment to the weakest and most vulnerable in society. It may come down to the vote, moral sentiment or tribal affiliations. And that will not be enough to extend human rights universally. In the name of utility, the society might not feel so impeded limiting social inclusion to those like us, 'us' being the decision makers who determine which common characteristics render embodied persons eligible for human rights protection. Nicholas Wolterstorff says, 'Our moral subculture of rights is as frail as it is remarkable. If the secularisation thesis proves true, we must expect that that subculture will have been a brief shining episode in the odyssey of human beings on earth.'

Marking the 60th anniversary of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, Irish poet Seamus Heaney said:

Since it was framed, the Declaration has succeeded in creating an international moral consensus. It is always there as a means of highlighting abuse if not always as a remedy: it exists instead in the moral imagination as an equivalent of the gold standard in the monetary system. The articulation of its tenets has made them into world currency of a negotiable sort. Even if its Articles are ignored or flouted — in many cases by governments who have signed up to them — it provides a worldwide amplification system for the 'still, small voice'.

The concept of human rights has real work to do whenever those with power justify their solutions to social ills or political conflicts only on the basis of majority support or by claiming the solutions will lead to an improved situation for the mainstream majority. Even if a particular solution is popular or maximises gains for the greatest number of people, it might still be wrong and objectionable. There is a need to have regard to the wellbeing of all members of the community. By invoking human rights, we affirm that 'each and everyone's well being, in each of its basic aspects, must be considered and favoured at all times by those responsible for co-ordinating the common life'

Professor Henkin neatly summarises the varying perspectives on the origin and basis of human rights, espousing the centrality of the idea in any society committed to freedom, justice and peace for all:

Although there is no agreement between the secular and the theological, or between traditional and modern perspectives on human beings and on the universe, there is now a working consensus that every man and woman, between birth and death, counts, and has a claim to an irreducible core of integrity and dignity. In that consensus, in the world we have and are shaping, the idea of human rights is an essential idea.

'Human rights' is the contemporary language for embracing, and the modern means of achieving, respect and dignity for all.

The market of the NDIS will ensure the protection and progressive realization of the human rights of persons with disabilities and their carers if and only if there is a safety net for those exploited by incompetent providers and for those who make ill-informed decisions for their long term care. We need to ensure that the reach of the NDIS extends to the poor, less educated, less connected person living in remote Australia as well as to the middle class, educated, well connected city dweller. We need to ensure that the person with disabilities who falls just on the 'wrong' side of the line for coverage understands why she does not qualify and how she will be adequately cared for. We need to educate the public and bring them with us explaining how differential treatment for 12 per cent of those with disabilities works not only to enhance their choices and human rights but also contributes to the common good and the protection of human rights of those falling outside the scheme's immediate application. A market of choice for some can contribute to the enjoyment of human rights by all, but that will be a regulated market with a robust safety net.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at Australian Catholic University, and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is professor of law at Australian Catholic University, and adjunct professor at the College of Law and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University.