‘For the majority of seniors, the biggest threat to their well-being isn’t an accident or health,’ Stephanie Beatriz’s Didi observes in A Man on the Inside. ‘It’s loneliness’.

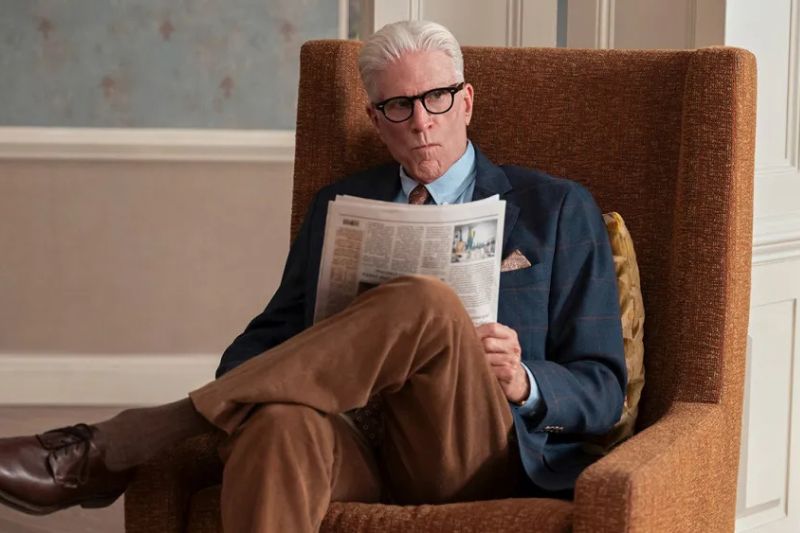

The new Netflix series, created by Mike Schur (Parks and Recreation, The Good Place) is ostensibly about Ted Danson’s Charles going undercover in a retirement community to investigate the disappearance of a resident’s necklace. But it’s really about the value of connection, the lingering ache of loss and the challenge of finding purpose as we age.

Urbane and accomplished, Charles has fallen into a rut following the death of his wife from dementia. Now retired from his work as a college engineering professor, he has drifted into a meaningless routine. He goes on long, aimless walks. He cuts articles from the paper and mails them to his daughter, Emily. She worries about him.

When Emily suggests that Charles take up a hobby to fill his days, he goes one better, answering an ad in the paper looking for an older person willing to go undercover for an investigative assignment. This brings him in contact with Lilah Richcreek Estrada as Julie, a no-nonsense private investigator somewhat put out to be working with such an elderly spy. While their first scene together pokes gentle fun at Charles and his competing applicants’ unfamiliarity with technology, A Man on the Inside has its sights on something warmer and more layered than mining straightforward laughs.

Soon, Julie selects Charles for the assignment and moves him into the upmarket Pacific View Retirement Community. Despite her instructions to keep a low profile, he starts getting to know the other residents and has a grand old time. It’s a delight to see Danson – arguably the greatest of all sitcom actors – fizzing with excitement as Charles warms to the novelty and joy of potentially solving the puzzle of the theft but also to the feeling of being useful again.

One of the marvels of A Man on the Inside is how the plot keeps chugging forward and the mystery of the theft keeps unfolding even as it finds time to develop subplots and flesh out the characters in Charles’ new home. It’s a more vibrant and detailed set of older characters than we usually see on screen; there’s Gladys, a good-natured former costume designer, now living with dementia. There are vivacious best friends Florence and Virginia. Then there’s the lugubrious, lonely Calbert, who moved to San Francisco to be closer to his son but rarely sees his workaholic offspring. Often the residents are chatty, catty and sexually curious. They can even be jerks, like the jealous, cigar-chomping Elliott. Overseeing them all is Didi, a resourceful and organised but perpetually underpaid managing director of the facility.

As is often the case with Schur’s creations, there’s an unusual level of ambition and social commentary running through A Man on the Inside. His Parks and Recreation (co-created with frequent collaborator Greg Daniels) was, in part, a study of declining trust in institutions and an optimistic argument for the value of government work concealed in the familiar vehicle of a workplace comedy. Even more ambitious was The Good Place, a twisty fantasy-comedy concerned with the weighty question of what it means to be a good person. Here, he’s working with a more muted palette than either of those shows but again tackling big questions of how we can honour our past while living for today.

'The conclusion achieves the Aristotlean ideal; it’s both surprising yet inevitable. It wraps up the narrative in a satisfying fashion while staying true to the show’s tone and its humanist, anti-ageist core, providing a clear-eyed look at how connection can help us live with loneliness and loss.'

At times, A Man on the Inside brings to mind the idea of the happiness curve, a concept popularised by Jonathan Rauch, which suggests many people experience happiness in a U-shaped curve, their contentment dipping as they reach middle age and then rising steadily in their later years. At one point, a gleeful Charles declares the largely responsibility-free socialising of his new community is “like high school”. In another scene, Julie chides Charles for partying too hard and wearily observes notes he has gone to sleep in his clothes with a full pizza on his back. The parent has returned to playing the role of the child.

Yet A Man on the Inside recognises that achieving genuine social connection can be elusive. Charles’ natural amiability allows him to become fast friends with many of the residents. Calbert, however, proves the toughest nut to crack but the pair eventually bond. A scene where they meander through a sun-dappled San Francisco, sharing their favourite sights and spots with each other, is among the series’ most rewarding.

The finale paves the way for a second season, though a second spy mission for Charles may provide diminishing returns compared to this perfectly formed debut run. Will the central conceit feel increasingly contrived, as it has for another show centred on ageing sleuths, Only Murders in the Building? For now, though, the conclusion achieves the Aristotlean ideal; it’s both surprising yet inevitable. It wraps up the narrative in a satisfying fashion while staying true to the show’s tone and its humanist, anti-ageist core, providing a clear-eyed look at how connection can help us live with loneliness and loss.

Daniel Herborn is a journalist and novelist based in Sydney. His writing has appeared in The Saturday Paper, The Monthly, The Guardian, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, and others.

Main image: Ted Danson in A Man on the Inside (Colleen E. Hayes / Netflix).