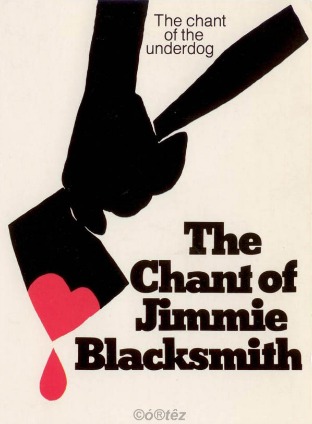

In Thomas Keneally's 1972 post-colonial novel The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, two white clerks bicker about impending Federation. One, an Englishman, suggests that 'there's no such thing as an Australian', other than in the 'imaginations of some poets and at the editorial desk of The Bulletin'. 'The only true Australians are ... the Aborigines.' 'Jacko', his zealous young companion retorts, is 'an honest bastard, but he's nearly extinct … It's sad, but he had to go.'

In Thomas Keneally's 1972 post-colonial novel The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, two white clerks bicker about impending Federation. One, an Englishman, suggests that 'there's no such thing as an Australian', other than in the 'imaginations of some poets and at the editorial desk of The Bulletin'. 'The only true Australians are ... the Aborigines.' 'Jacko', his zealous young companion retorts, is 'an honest bastard, but he's nearly extinct … It's sad, but he had to go.'

The young clerk seems to be of the view, reflected by others elsewhere in the novel, that Federation represents atonement, or at least a chance to draw a line through a history of colonial hardship and Aboriginal slaughter. The novel evokes a treacherous national identity crisis; this is reflected in the person of its half-caste antihero Jimmie, who is so infected by it and so oppressed by the latent racism that it elicits, that he eventually explodes in murderous rage.

More than a century after Federation, Australia has yet to resolve this tension between a romantic notion of what 'Australia' is, and the depravities that were undertaken to attain it. It may be couched in more polite terms, but it rears its head in ham-fisted and fundamentally disrespectful approaches to Indigenous policy, such as recent moves by the Coalition Government that threaten to undercut the spirit of Native Title legislation.

Senior Aboriginal leaders and advocates for Aboriginal rights have raised concerns about a strategy employed by Indigenous Affairs Minister, Country Liberal Party Senator Nigel Scullion. During what Frank Vincent QC describes as a fly-in, fly-out mission, Scullion obtained memorandums of understanding from members of Gunbalanya and Yirrkala townships to negotiate 99-year leases.

East Arnhem elder Dr Djiniyini Gondarra describes this as being part of a 'blitz' designed to encourage other communities around the country hastily to sign similar deals, ostensibly for their own betterment. Gondarra expressed fury about the manoeuvre in The Australian: 'We … do not want further controls put over our society,' he said. 'We want the shameful march of colonisation to end.'

Vincent, former prime minister Malcolm Fraser, Alastair Nicholson QC and Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, outspoken elder from Utopia, NT, picked up this theme during a forum in Melbourne recently. It is 'technically correct', said Nicholson, that the 99-year leases don't negate Aboriginal ownership. But they do pit a particularly 'western' notion of ownership against the traditional Aboriginal concept of custodianship, which is at the heart of Native Title law. Taking away that custodianship for the span of four generations is as good as an acquisition.

Vincent, former prime minister Malcolm Fraser, Alastair Nicholson QC and Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, outspoken elder from Utopia, NT, picked up this theme during a forum in Melbourne recently. It is 'technically correct', said Nicholson, that the 99-year leases don't negate Aboriginal ownership. But they do pit a particularly 'western' notion of ownership against the traditional Aboriginal concept of custodianship, which is at the heart of Native Title law. Taking away that custodianship for the span of four generations is as good as an acquisition.

This is not a partisan issue. As Fraser pointed out, it continues a tendency towards government interventions (such as the Intervention and its euphemistically dubbed offspring, Stronger Futures) from successive governments of both sides, that eschew consultation in favour of paternalism. This is inherently disempowering and marginalising. And the fly-in, fly-out approach negates the possibility of genuine informed consent by the signatories.

Fraser suggested that one alternative approach may be for Aboriginal communities to preempt the government interventions, enlist the support of sympathetic developers and lawyers and take development into their own hands, in a way that remains respectful of the traditional values and practices of custodianship. Even this may be easier said than done: Kunoth-Monks intimated that her own attempts to follow such a course had been stifled at (then Labor) government level by a Minister who she sensed preferred paternalism to empowerment.

What is the way forward? Gondarra calls on the Government 'in the spirit of partnership' to 'declare their interests openly and tell us why they think 99-year leases are good things, not start with the premise they are best for us and then try to persuade us. They should allow a process of option creation as our people come to the government with our own ideas. Finally with free, prior and informed consent, our people and the government can make mutual agreements that will progress Indigenous interests, not only government interests.'

In 2013 we are well past the point of lolling back on cushiony words like Reconciliation and the fading memory of the National Apology. 'We no longer want compassion,' says Kunoth-Monks, gravely. 'We want our rightful place in this land of ours.' It's time to do the hard work. An open and transparent exchange based in mutually respectful conversation, such as that proposed by Gondarra, would surely go a long way towards achieving this, and might put the ghost of Jimmie Blacksmith to bed once and for all.

Tim Kroenert is the assistant editor of Eureka Street.

Tim Kroenert is the assistant editor of Eureka Street.

Pictured: Malcolm Fraser, Rosalie Kunoth-Monks and Frank Vincent QC in conversation.