While territorial disputes in the South China Sea and the Sea of Japan attract headlines, few Australians realise that their own country's borders are not as settled as commonly assumed.

While territorial disputes in the South China Sea and the Sea of Japan attract headlines, few Australians realise that their own country's borders are not as settled as commonly assumed.

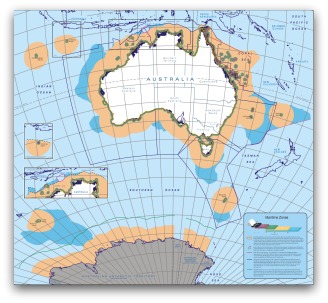

Looking at a map of the Australian coastline gives no clue about how far Australia's territorial claims extend. As a result, Australian policy makers aren't eager to embrace suggestions that Asian countries disputing possession of small islands and rocky outcrops should resolve their differences by assigning ownership to the closest country.

Australia has sovereignty over Kussa, a small island in the Torres Strait, that is only a couple of hundred metres from Papua New Guinea's shore at low tide. Australian possessions such as Christmas Island are much closer to Indonesia than Australia.

In one case, the CIA's World Fact Book notes, 'Indonesian groups challenge Australia's claim to Ashmore Reef'. Moreover, the Indonesian parliament is yet to ratify a 1997 treaty to establish an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) with Australia. East Timor has left the issue of its final maritime boundary with Australia in abeyance.

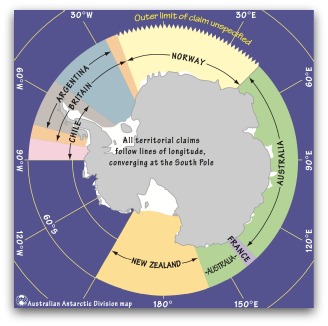

Perhaps the greatest uncertainty surrounds Australia's claims to sovereignty in the Antarctic. Most countries, including the US, don't recognise Australia's claim to 42 per cent of Antarctica. Six nations — Argentina, Chile, France, NZ, Norway, and the UK — claim a total of around 38 per cent. About 20 per cent is unclaimed. However, Australia, Chile and Argentina have also made offshore EEZ claims, but the World Fact Book says, 'These zones are not accepted by other countries'. Australia's EEZ claim covers two million sq km.

Australia also claims the Heard and MacDonald islands in the sub-Antarctic, about 4100km south-west of Perth, and Macquarie Island about 1500km south of Hobart. It also claims an EEZ around each. Although Macquarie Island is closer to Invercargill than Hobart, fortunately New Zealand remains a gracious neighbour.

Australia supports the 1961 Antarctic Treaty that aims to keep the continent demilitarised; promote international scientific cooperation; and exclude any new claim, or enlargement of an existing claim, during the life of the treaty. The ban on any enlargement of an existing claim may help explain why so few countries recognised Australia's subsequent declaration of an EEZ off the continent. In 1991, an addition to the treaty imposed a ban on minerals exploration, which is up for renegotiation in 2048. The treaty itself has no expiry date.

A Lowy Institute paper argued last August that Australia should regard its Antarctic claims as primarily a national security issue and include defense personnel in its scientific presence there. The paper's author Ellie Fogarty, writing while on leave from the Prime Minister's department, referred to unspecified emerging 'threats' to Australia's 'ability to preserve its sovereignty claims'. Her paper wanted the next Defence White Paper to consider including the Antarctic within the Australian military's area of operational interest.

The US, Russia, China and India, among others, maintain research bases without claiming any territory. Fogarty is stretching a long bow, however, when she sees as disturbingly nationalistic China's description of its recent ascent of the Antarctic Plateau within Australia's territory as a 'conquest'. New Zealanders described Edmund Hilary's ascent of Everest as a 'conquest' without implying they were making an incipient claim to sovereignty.

The US's research station at the South Pole covers 'territory' of each claimant state. It has other stations within areas claimed by Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Chile and Britain.

Australia's chances of maintaining its claim to 42 per cent of the continent will weaken if the prospects for oil production and mining appears commercially attractive. Military action could not secure Australia's position if the US, for example, decided in future decades that it owned part of Australia's huge claim.

Australia's chances of maintaining its claim to 42 per cent of the continent will weaken if the prospects for oil production and mining appears commercially attractive. Military action could not secure Australia's position if the US, for example, decided in future decades that it owned part of Australia's huge claim.

Australia would also be hard pushed to object if most countries, including the US, decided to reject all claims to sovereignty and preserve the Antarctic as an international wilderness area. Alternatively, there may be an international agreement to allow limited commercial development with the proceeds shared globally. In either case, the national security importance of Australia owning 42 per cent continent's would be rendered irrelevant.

Australia's possession of islands close to PNG is a legacy of Queensland's annexation of almost the entire Torres Strait in the 1870s. The Whitlam government tried to modify the colonial arrangements before PNG's independence in 1975, but faced stiff opposition from the then Queensland premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

The Fraser government's foreign minister Andrew Peacock persevered with complex negotiations that produced a new treaty in 1978. Australia retained possession of the islands, but gave PNG citizens greater travel access and fishing rights in the strait. The arrangements, however, remain subject to political volatility in Port Moresby.

Further west, Australia won potentially lucrative rights to petroleum resources as part of highly favourable sea bed agreements with Indonesia in 1971 and 1972. These set boundaries well to the north of the median line between the two countries. The Australian Secret Intelligence Service helped by providing information about Indonesia's negotiating position. But the outcome was mostly due to the way international law allowed Australia to claim the seabed to the full extent of its continental shelf that (ignoring troughs) stretches close to Indonesia.

International law was not so accommodating when Australia drew up a 1997 treaty to establish an EEZ for resources on or above the seabed, such as fish. The law allows the zone to extend 370km offshore, but the boundary is usually set along the median line where countries are close enough to create an overlap.

Although the Indonesian parliament is yet to ratify the treaty, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade says, 'Consistent with international law, during the period between signature and ratification, Australia and Indonesia are obliged to refrain from acts contrary to the purpose of the Treaty.'

Developments in international law also put East Timor in a stronger position to negotiate a better deal on its seabed border with Australia after independence in 2002. Although Australia's seabed boundary with Indonesia left a gap below East Timor, new government in Dili agreed in 2007 to share petroleum revenues with Australia over a bigger area for 50 years and postpone the determination of formal boundaries.

However, Hamish McDonald recently pointed out in the Sydney Morning Herald that two months before East Timor gained independence, Australia withdrew from the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea and from the maritime jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice so the tiny nation could not take Australia to court over disputed oil fields. McDonald noted that Tony Abbott, overlooked Australia's withdrawal when calling for disputes in the South China Sea to be resolved 'in accordance with international law'.

However, Hamish McDonald recently pointed out in the Sydney Morning Herald that two months before East Timor gained independence, Australia withdrew from the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea and from the maritime jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice so the tiny nation could not take Australia to court over disputed oil fields. McDonald noted that Tony Abbott, overlooked Australia's withdrawal when calling for disputes in the South China Sea to be resolved 'in accordance with international law'.

DFAT says there will be no change to 'the position of successive Australian governments that negotiations are the most appropriate way to settle maritime boundary delimitations with neighbouring countries'. So Australia will continue to share China's rejection of the international dispute settlement procedures for maritime zones.

The Indonesian government accepts Australian sovereignty over the Ashmore and Cartier islands, which Geoscience Australia says are 320km off Australia's northwest coast and approximately 170km south of the Indonesian island of Roti near West Timor. A University of NSW historian Ruth Balint says the shortest distance from Roti is less 80km.

In 1933, Britain handed formal administration of the now uninhabited islands to Australia, which later allowed controlled access for traditional Indonesian fishermen. Some Indonesians who question Australian sovereignty say there is evidence that the Dutch regarded the islands as part of their East Indies' colonial territory. So far, the challenge to Australia's continued sovereignty remains subdued.

The Indonesian government also accepts that Christmas Island is part of Australia, despite being only 360km south of Java. The closest part of the West Australian coast is 1560km away at Exmouth. Britain transferred administration of the island from its Singapore colony in 1958.

Although now a detention centre for asylum seekers, Christmas Island was previously known as an 'unsinkable' aircraft carrier that extended the range of Australian fighter planes. So was the Cocos group (975km further west), which is also closer to Indonesia than Australia. Despite being in the minority, Air Marshal David Evans argued after retiring in 1985 that Christmas Island would not be worth defending if threatened.

Both sides of politics insist that the attempt to discourage asylum seekers by excising the Ashmore, Christmas and Cocos islands from the nation's immigration zone in no way weakens Australian sovereignty.

Walkley award winning journalist Brian Toohey is a columnist with the Australian Financial Review. Map 1: 'GA3746(5) oz maritime zones' (Geosciences Australia). Map 2: 'Antarctic territorial claims' (Australian Antarctic Division). Click maps to enlarge.

Walkley award winning journalist Brian Toohey is a columnist with the Australian Financial Review. Map 1: 'GA3746(5) oz maritime zones' (Geosciences Australia). Map 2: 'Antarctic territorial claims' (Australian Antarctic Division). Click maps to enlarge.