Thanks to Bill Mason, who not only invited me to speak this evening but also suggested the topic, knowing my interest in religion and politics. He was so keen on this topic that eventually, after failing to recruit anyone else, I volunteered early last year. Subsequently I was awarded a fellowship by the Australian Prime Ministers Centre at Old Parliament House to pursue this topic seriously. So I have many people to thank for the great satisfaction researching this topic has afforded me.

Thanks to Bill Mason, who not only invited me to speak this evening but also suggested the topic, knowing my interest in religion and politics. He was so keen on this topic that eventually, after failing to recruit anyone else, I volunteered early last year. Subsequently I was awarded a fellowship by the Australian Prime Ministers Centre at Old Parliament House to pursue this topic seriously. So I have many people to thank for the great satisfaction researching this topic has afforded me.

The origins of the topic lie in the public debate generated by the religious beliefs of two recent prime ministers, John Howard and Kevin Rudd. Among many other comments Rudd has been described as 'the most sincerely Christian Prime Minister Australia has had for a very long time', and as having identified himself more strongly as being a 'practicing Christian' than any PM since WW2. Rudd and Tony Abbott, the current leader of the Opposition were described as 'the two most overtly religious party leaders Australia has seen'. The ingredients are fascinating and the mass media has increasingly taken an interest.

In a talk such as this I can only attempt to give you a flavour of the beliefs of as many prime ministers as possible. In passing I should point out that even ascertaining their religious beliefs, including the basic matter of denomination, is often no easy task. For some PMs and their biographers religion means very little. Even in the case of some major figures, such as Alfred Deakin (was he a Christian as well as spiritualist who took part in seances?), Billy Hughes (was he agnostic or Christian?) and Malcolm Fraser (was he Anglican or Presbyterian?) experts differ. Part of the answer lies in the fact that like many other people their beliefs changed during their lifetimes.

Australian prime ministers live in a country where religious beliefs are often, in sociologist Gary Bouma's terminology, low temperature like our attitudes to life. But attitudes have also changed. At least until 1966, about when Sir Robert Menzies long period in office ended, attitudes were dominated by social, economic and political sectarianism (deep differences based on religion). Since about that time religious adherence has been in decline, secularism has grown as has ecumenism between denominations. The issues that defined religious believers have also changed. Once upon a time the issues were ones like education and temperance that divided denominations. Now the issues are related to life, death and sexuality and divide believers from non-believers.

Australia's leaders have all come from the mainstream Christian denominations: Anglicanism, Catholicism and the denominations that make up what is now the Uniting Church. The minor denominations have had few if any followers. In the early days Deakin was a spiritualist and John Christian Watson was twice married in the Sydney Unitarian Church (Unitarians do not believe in the supernatural). John Curtin flirted with the Salvation Army, Bob Hawke's father was a Congregational minister and Julia Gillard's parents were Baptists. These last three all left the faith of their youth.

Party differences are also an important part of the story. The Liberal Party and its predecessors have been the party of Protestantism until the last decade or so. The Labor Party was greatly influenced by Methodism in its early years before a Catholic ascendancy between the two great Labor splits during World War 1 and the Cold War of the 1950s. There was also always an important secular humanist strand in Labor which has become more important over the last 50 years.

Denominational differences are important. Anglicanism and Presbyterianism have been the religious beliefs of the establishment (In Britain the Church of England has been called the Tory Party at prayer). Catholicism and the reformed churches have been the religious beliefs of working men and women. Expectations about appropriate participation also vary. For instance, there is no easy equivalent in other denominations of the various terms used to describe Catholics such as 'practicing', 'devout' or lapsed.

Prime ministers have also moved and married between denominations like other Australians. Dame Enid Lyons converted from Methodism when she married the Catholic Joseph Lyons, but Ben (Catholic) and Elizabeth (Presbyterian) Chifley were married in a Presbyterian church in Sydney to avoid embarrassment to their families in their home town of Bathurst. Several future prime ministers have taken the denomination of their wives, notably John Howard and Kevin Rudd and earlier Robert Menzies, beginning with their marriage. This phenomenon has been described critically as cafeteria Christianity (picking and choosing), but it has occurred naturally. It should be noted however that generally future PMs have gravitated towards the higher-status denominations, Anglicanism and Presbyterianism, from the lower status Catholicism and Methodism. Bill McMahon moved from Catholicism to Anglicanism as did Rudd. Howard moved from Methodism to Anglicanism, and Menzies moved from Methodism to Presbyterianism. The reasons are various and usually not devious but it is an interesting pattern nevertheless.

Australian Prime Ministers

There have been twenty seven prime ministers from Edmund Barton to Julia Gillard. The first twenty six were men. A minority have been Labor. Overall their differences as regards Christian denomination and religious observance reflect those in Australian society. But there is a twist in the tale.

By my calculations less than half of our prime ministers (11) have taken their religion seriously. They include the two longest serving prime ministers, Menzies and Howard. A clear majority (16) have been either nominal Christians only or agnostic, including the third longest serving PM, Bob Hawke.

Religious Beliefs

Faith or religious belief has a number of elements. Untangling them is a task in itself as it includes beliefs and actions. In this talk it will be defined broadly. The first meaning is declared religious belief or non-belief and denominational affiliation. The second is religious practice (known as religiosity) and the level of intensity of belief. The third is membership of a religious community with all the associated ethnic and class characteristics. Members of a religious community may have only residual beliefs and the association, though no less serious for the individual, may be primarily cultural or tribal.

My study of the prime ministers enables a simple five-part categorization of them according to their faith. The five categories are observant Christians (regular church-goers), conventional Christians (occasional church-goers), nominal Christians (attendance only on formal occasions), articulate agnostics, who speak publicly about their disbelief, and nominal agnostics, who may be judged by their actions.

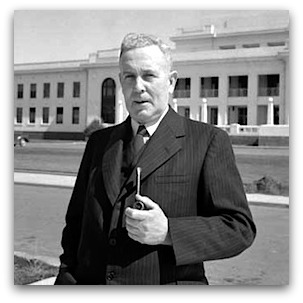

Nine prime ministers (Deakin, Fisher, Cook, Scullin, Lyons, Forde, Chifley — pictured — Howard and Rudd) have been observant Christians). Two (Menzies and Keating) have been conventional Christians. Ten (Barton, Watson, Reid, Bruce, Page, Fadden, McEwen, McMahon, Gorton and Fraser) have been nominal Christians. Five (Hughes, Curtin, Whitlam, Hawke and Gillard) have been articulate atheists or agnostics. One (Holt) was a nominal atheist or agnostic.

Two Personal Stories

Howard had no truck with denominational differences: 'The fundamentals of Christian belief and practice which I learned at the Earlwood Methodist Church have stayed with me to this day, though I would not pretend to be other than an imperfect adherent to them. I now attend a local Anglican church, denominational differences within Christianity meaning nothing to me' (John Howard,LR, 15)

Chifley worried about his status as a Catholic. It is said that Ben Chifley always sat at the back of St Christopher's, reflecting his uncertainty about how the church regarded him because of his mixed marriage in a Presbyterian church in Sydney. I had hoped to have Chifley's chair with me this evening but it has been loaned to the National Museum for an exhibition on the contribution of Irish-Australians to Australia.

Affiliation

Catholics: There have been five Catholic prime ministers. Their beliefs have always been accorded special attention, both in their own right and with regards to their supposed deference to their priests and bishops. The pattern of their beliefs is accorded a special intensity, so that the term 'devout' is applied almost solely to Catholics as its opposite 'lapsed' (the same is true of the term 'practicing'). Catholics themselves use these terms as well as others such as 'cultural' and 'tribal' to describe their belief systems and their attachment to their religious communities. There is also a sense in which Catholics are referred to collectively (the 'Catholic community') in a way that is rarely the case with other denominations.

After failing to achieve the top position during the first thirty years (and eight prime ministers), despite making up 20% or more of the Australian population, Catholics had great success with four prime ministers over about twenty years (1929-1949) during the first period from the first Catholic, Labor's James Scullin (who was present at the laying of the foundation stone for the National Shrine to Our Lady Help of Christians (now Archbishop's House in Canberra), to Labor's Ben Chifley, including Joseph Lyons of the United Australia Party and the short-term Labor PM Frank Forde. Geoffrey Blainey later commented on this apparent over-representation.

But overall their percentage is probably less than their percentage of the whole population (now over 25%) and there has been only one Catholic prime minister, Paul Keating, in the later period. Only Keating of the five Labor Prime Ministers since the Labor-DLP Split has been Catholic and the Liberal Party has yet to produce a Catholic PM, though the past three Liberal Leaders of the Opposition have been Catholic and the next Liberal prime minister may well be a Catholic.

The first four Catholic PMs, while very different in many ways, share one characteristic. They were all practising Catholics. St Christopher's Cathedral in Canberra honours them among its famous parishioners for this reason.

Scullin was the first Catholic prime minister. He was active in the Catholic Young Men's Society. John Molony is somewhat scornful of the intellectual character of Scullin's faith: 'Scullin's knowledge of Catholic social teaching was minimal and had no appreciable effect on his consciousness'. But he acknowledges that 'he remained committed to his faith and its practice throughout his life'.

Lyons, who began political life in the Labor Party before switching to the conservatives, is variously described as a 'loyal' and 'devout' Catholic. He and his wife are known for their very large family, a Catholic characteristic in the eyes of many. According to their biographer Anne Henderson Joe and Enid were 'very faithful Catholics' and he 'went to Mass a bit on the road, even as PM'.

Forde, who was only briefly Prime Minister, had an unexceptional traditional Catholic education and life, common among many Catholic Labor MPs of his generation.

Chifley's faith story was complicated because of his mixed marriage. He married Elizabeth McKenzie in the Glebe Presbyterian Church in Sydney, to avoid controversy and embarrassment to their families in their home city of Bathurst. This was a big step at those times to go counter to the 1908 papal decree, called Ne Temere, against such mixed marriages. Bravely he decided that 'One of us had to take the knock. It better be me'. Yet he continued to attend Sunday Mass regularly in Bathurst and Canberra, but he felt like an outsider and, at St Christopher's in Canberra, reputedly sat at the very back of the church. He reflected to a constituent later that 'I do go to church regularly, but I am afraid the church does not regard me as one of its model children'.

Eventually Chifley, prior to the Labor Split, was at odds with conservative Catholics within his own party, whom he condemned as religious fanatics for their anti-Communism.

Keating on the other hand is best regarded as a cultural or tribal Catholic. According to one biographer, Edna Carew, 'The Keating family illustrates the traditional pattern of Irish-Catholic life in Australia'. He is a typical member of the post-Labor Party Split NSW 'Catholic Right'. His father Matt had been a member of the anti-communist ALP Industrial Groups, and probably of the Catholic Social Studies Movement too.

According to another biographer, Michael Gordon, he 'attended Mass irregularly but was faithful to the tenets of the church'. He exemplifies Irish-Catholicism in its Labor links. Bankstown, where Keating grew up, was once known as Irishtown. Paul Kelly emphatically describes Keating as a Catholic. He quotes Keating's chief of staff, Don Russell, as saying that 'he was always the Catholic boy driven to do good'.

In his own words Keating describes the link between faith and politics in terms of community tensions and perceived discrimination against Catholics. In relation to his experience of sectarianism he recalled: 'I resented it. You wouldn't have those doors closed against you if you weren't a tyke'.

Anglicans: The first of the so-called establishment faiths, because of its upper middle class following and its English connections, was the Church of England (Anglicans), known as the Anglican Church of Australia since 1981. 'Tricia Blombery described one of the problems of the church (as well as being a great source of its strength) as being its 'history of being the church of the British, of the ruling group, and of the privileged'. The church, through their governing boards and their names, is associated many of Australia's elite private schools, such as Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra Grammar Schools.

Anglicans were for many years the largest of the Christian denominations, until overtaken by Catholics at the 1986 Census. At the 1901 Census 40% of Australians were Anglican. While large, Anglicanism also suffers from frequent nominalism and a relatively low regular church attendance.

There have been about nine Anglican prime ministers. This means that fewer Australian prime ministers than might be expected, given the size and prominence of the denomination, have actively identified as Anglicans, though many have attended Anglican schools and colleges. Stanley Melbourne Bruce is a case in point. However the two most recent prime ministers, John Howard and Kevin Rudd, have been observant, church-going Anglicans.

Howard had a Methodist upbringing and attended Canterbury Boys High School rather than an Anglican private school. He led a Cabinet renowned for its Christian identification. Yet he himself was uncomfortable being called a Christian leader in public and when introduced as such he emphasised that he respected 'fully the secular nature of our society'. He remains a monthly regular church-goer in his retirement from public life.

Rudd had a Catholic upbringing through his mother's faith and attended first a Catholic school and then Nambour High School. He became an Anglican about the time he married Therese Rein in Canberra. Rudd attended church weekly. From the time of the 2004 election aftermath he began a political campaign to strenuously encourage the electorate to recognise and reward the Christian ethos within the Labor Party.

Presbyterians: The second of the establishment Protestant denominations is Presbyterianism, which is associated particularly with Australians of Scottish background. At the time of Federation Presbyterianism was the fourth largest denomination, making up 11% of the population. Two of Australia's longest serving prime ministers, Sir Robert Menzies and Malcolm Fraser, were of Scottish Presbyterian ancestry. Gough Whitlam, too, was raised in a Presbyterian household. This means that the three great patricians of post-war Australian politics, at least by reputation, have had Presbyterian connections. But strictly speaking there have been only three Presbyterian prime ministers, including Menzies, though several more, including the Country Party's Arthur Fadden and John McEwen, had Presbyterian antecedents.

Menzies was notably Scots in his personal identification. His father James, though not by first choice a Methodist has been called 'a dedicated and highly emotional Methodist lay preacher'. Growing up in Jeparit in country Victoria, where there was no Presbyterian church, Menzies lived in a largely Methodist world. Yet he maintained Presbyterian roots through his grandmother and from the time of his secondary school education in Melbourne attended a Presbyterian church. His wife Pattie was Presbyterian too and they married in a Presbyterian church. For the rest of his life he described himself as just 'a simple Presbyterian'.

His most famous statement of his values, 'The Forgotten People' radio address, included a religious element. One of his themes in this address, though not the most important one, was spirituality.

If human homes are to fulfil their destiny then we must have frugality and savings for education and prayers.

We have homes spiritual. This is a notion which finds its simplest and most moving expression in 'The Cotter's Saturday Night' of Burns. Human nature is at its greatest when it combines dependence upon God with independence of man.

Fraser was notably of the Western Districts establishment. His grandfather, Senator Simon Fraser was a Scots Presbyterian too. But Fraser himself, following his marriage to his wife Tamie, appears to have become an Anglican.

Much earlier, against the ideological tide of the church, Labor produced its own Presbyterian prime minister, Andrew Fisher. Few Presbyterians were socialists but Fisher was a friend and colleague of the Scot Keir Hardie, a Christian socialist as Kevin Rudd commonly points out, and one of the founders of the British Labour Party. Fisher, brought up in a staunch Presbyterian household, was a Sunday school superintendent as a young man, observed the Sabbath, and was teetotal as his faith demanded.

Among early prime ministers George Reid was also Presbyterian. He was the son of a Presbyterian Minister but he himself was only nominal in his adherence.

Methodists: The fourth major denomination, third largest at 13% in 1901, was Methodism, known in part for its social justice values as well as an evangelical strand. There has been only one Methodist prime minister; but the wider role of the church has been greater than that.

Menzies and Howard were brought up Methodists, by force of circumstance apparently; although as late as 1975 Howard described himself as a 'communicant member of the Methodist church'.

Howard's Methodism, in particular, has been accorded particular attention. But Joseph Cook has been the only life-long Methodist among the prime ministers, which is something of a surprise given Methodism's role within the early Labor Party.

Cook grew up in the Primitive Methodist sect, and like many labour movement leaders in the NSW coalfields had been a Primitive Methodist preacher. His commitment to Methodism was life-long

Tribalism

Robert Menzies always described himself as merely a 'simple Presbyterian'. He took his Scots

Presbyterian roots seriously. The link between Scots ethnicity and Presbyterianism is notable also in the background of Malcolm Fraser.

But it is Irish-Catholicism that is the clearest example of the link between religious beliefs and ethnicity. It is evident in the beliefs of many Irish-Catholic MPs, but the best example among prime ministers is Paul Keating. According to commentators like Paul Kelly Keating's Catholicism was one of his defining characteristics. Yet Keating was not a practicing Catholic.

Non-Believers

Since June we have had a non-believer as prime minister. Gillard is in quite a long line of non-believers, beginning in the early years after federation, and in recent years agnostics have become just as common as believers. The line includes Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke.

But Gillard stands out because she has described herself not as an agnostic but as an atheist, perhaps the first prime minister to do so. Her position attracted particular attention not just because of this step but also because she followed Howard and Rudd and her election opponent was Abbott.

In fact after World War Two there were a number of Liberal prime ministers, including Holt, Gorton and McMahon, who showed little commitment to Christian beliefs. Holt is best described as an agnostic too. Even Sir Robert Menzies' Christian beliefs were merely conventional. This means that for the best part of fifty years between Chifley's loss in 1949 and Howard took office in 1996 Australia was led by prime ministers (nine of them) who were not observant Christians.

The number of agnostic and secular prime ministers, while fewer than the religious believers and perhaps even fewer than their percentage of the population, is quite high in comparison with British Prime Ministers and American Presidents.

Labor, despite being the party of Catholics for forty years, is also the party of agnostics. Agnosticism is acceptable for Labor leaders within the party on account of this in a way that does not apply to the Liberals where adherence is more the norm. The four most prominent prime ministers in this category are Billy Hughes (when he was Labor), John Curtin, Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke. Of the three Hawke has given the most extended explanation of his loss of Christian faith, which occurred during and after travelling as a young man in India as a member of a Christian delegation to the World Conference of Christian Youth.

For the other two the explanation was more intellectual and seems to have occurred even earlier during their secondary education.

Curtin replaced his Christian faith with his attachment to socialism. According to Geoffrey Serle , 'Labor and Australia were his two causes'. Curtin also rejected his Irish heritage. Towards the end of his life he began to add 'God Bless You' to the conclusion of his public speeches. Perhaps, speculates Serle, he was 'groping towards religious consolation'.

Whitlam made an intellectual departure as a school-boy. He said, in typical fashion, that he had no working relationship with God, but 'an intense interest in the Judaeo-Christian religion'.

After he entered Parliament in 1953 the Labor Party was mired in the Labor Split that led to the emergence of the Democratic Labor Party. He had plenty of opportunity to reflect on the divisive interaction of religious beliefs and politics. He, like other Labor figures of his generation and even later, was disinclined to court trouble by speaking about his religious beliefs in public. This attitude was shared by many ordinary Australians and became part of entrenched Australian cultural attitudes.

At Canberra Grammar School Whitlam won the divinity prize but it was held back by the headmaster because of his evident lack of faith. Although he once described himself as a fellow-traveller with Christianity he told his biographer Laurie Oakes that after attending St Paul's university college he only went to church once more and that was to be married. Whitlam's parents were staunch Presbyterians.

Hawke, 'a child of the Manse', made his agnosticism even more public than Whitlam, reflecting his much more open character. Later, in 1988, as he recalls in his later autobiography, he made a remarkable outburst against the rationality of Christian beliefs in the course of defending Aboriginal spiritual beliefs.

On the conservative side of politics it was inappropriate to declare disbelief, given the Protestant imagination of the Liberals. But Harold Holt is best described as an agnostic. It has been said that his only credo apart from dedication to advancing his career in politics was Kipling's 'If'.

Consequences

Electability

There are two issues here. First there is the JFK factor. Kennedy had to convince American voters in 1960 that Catholics could be trusted. He, in a famous speech, said that he was not the Catholic candidate but a candidate who just happened to be Catholic. Australia had already had four Catholic prime ministers by this stage (three Labor and one conservative of Labor origin). Just this year Tony Abbott used similar terminology and said that he was not a Christian politician but a politician who happened to be a Christian.

There is no suggestion that Catholics and/or religious politicians have not been electable. Some citizens are put off by religious values, just as some are put off by non-belief, but there are not enough of them to disqualify a religious candidate (or an atheist). Far from it. In some instances, as with Kevin Rudd, it can be an advantage.

But Catholics have sometimes found it difficult to take the prior step of becoming leader of a major political party. Catholics for many years have been locked into the less successful of the major parties: Labor.

Labor has been both the Catholic and the secular humanist party, while non-Labor has been the Protestant party. Four of the five Catholic prime ministers emerged while Catholics predominated in the Labor Party between 1916 and 1954.

Having said that, Kevin Rudd rose to the top of the Labor Party (so have state Labor leaders like Morris Iemma and Kristina Keneally) and Catholics are particularly prominent now within the Liberal Party. So advancement to the leadership for Catholics and/or religiously inclined MPs is now possible on both sides of politics

Vocation and Ethos

Altruism often stems from Christian beliefs. Religious upbringing was one factor that pointed some of our prospective PMs towards politics as a noble vocation. Fraser has stressed the importance in his case of the link between religion and public service: 'If I did not have that attitude to belief I would not have wanted to go into politics'. Keating has said that: 'Catholicism gives you this view that we are born equally and we die equally, and that no one of us is intrinsically worth more than another'.

Faith played some part in the career choices of our prime ministers even for those for whom religious belief waned. It is quite common for Labor MPs, including prime ministers, to link faith with their social justice aspirations and their choice of the Labor Party as their vehicle. Hawke has written that 'the basic Christian principles of brotherhood and compassion…would stay with me for the rest of my life…to guide me in my future career'. Howard, after years in Parliament, said that Methodism had instilled in him 'a sensitivity to social justice.. a sort of social justice streak'.

The religious vocations of parents played a part in the backgrounds of numerous prime ministers. Several, including Reid and Hawke, had fathers who were ministers, while several more, including Menzies, had fathers who were lay preachers. Cook had studied for the Methodist ministry.

For many future prime ministers it is also notable how their early involvement in church activities gave them an opportunity to hone their practical organizational skills that would prove so useful in later political life. They were joiners and organisational leaders from their youth onwards. Many held official posts in church youth groups, including Reid, Hawke and Howard.

Policy

The relationship between government policy and the personal values of the prime minister at the time is a big and complex issue. Whatever their own values may be they are surrounded by Cabinet ministers and public servants responsible for particular portfolios. They are also part of a system in which party policy sustains the non-religious character of the link between ideology and policy.

The impact of religious beliefs on government policy, often touted as a dangerous threat by defenders of the purity of the secular state, is more difficult to locate. Sometimes policy has been contrary to the religious beliefs of prime ministers, as in the case of the evolution of state aid for private religious schools. Several morality issues, such as abortion, have only had intermittent policy consequences because of the constitutional position. State rather than federal government has primary responsibility.

State aid to church schools, especially Catholic schools, makes an interesting case study. Various Catholic prime ministers failed to either introduce it or even argue for it, despite official church advocacy. In the 1930s and 1940s this applied to Scullin, Lyons and Chifley. The politics was not easy for them, of course, within Labor. Scullin reportedly said that he 'could not vote for the inclusion of a plank in the platform which would entirely disrupt the Labor movement', and it was little better within the conservative side. Authors like Patrick O'Farrell, Judith Brett, and Robert Murray confirm this. Brett says that the 'welcome' of Catholics into the Liberals was 'conditional' on them not acting politically as Catholics. Murray says that Catholics were expected to be 'conventional' Catholics and not press their claims on education. Perhaps life and death issues are the modern equivalent. Graham Freudenberg, Whitlam's biographer, famously concluded that 'the state aid controversy was ended in favour of the Catholic Church by two men-Menzies, the self-proclaimed 'simple Presbyterian' and Whitlam, the exemplar of the humanist heresy'. The Democratic Labor Party played its part as well.

Gillard is a contrary test case showing that atheists and believers often hold similar views on controversial social issues like opposition to gay marriage. Either that or she exemplifies the fact that the wider bureaucratic, political and electoral context of policy-making is more important than the personal views of any prime minister.

Conclusion

The twist in the tale is that while in general the spread and intensity of religious beliefs approximate those of Australian society, at any one time prime ministers can hold beliefs that are very different from those of their citizens. Deakin, Watson and Hughes were out of tune with their times in an age when a majority of Australians were Christians. So were Howard and Rudd at a time of low levels of religious observance.

Religious belief has played a major part in the adult lives of no more than half of Australia's 27 prime ministers. For some it has been a driving force and a central part of their public personality. But for many others it has been a trivial characteristic.

Sectarianism made religious denomination a controversial characteristic in Australian society until the 1950s at least. Prime ministers were caught up in sectarianism like everyone else, beginning with the very first prime minister, Edmund Barton, who was loudly criticised by some Australian Protestants for meeting the Pope in Rome (they conversed in Latin!). Lyons had to suffer silently the sectarianism directed at him during a 1935 visit to the United Kingdom, as it was presumed by some of those whom he met that he was a Protestant because of his party. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, for instance, even warned him against Catholics. But some did know that he was Catholic because he also suffered a 'No Popery' demonstration in Edinburgh.

More recently the dichotomy between observant believers of any denomination or faith and non-believers has become more important, fuelled by several factors including the global culture clash between Islam and Christianity.

Finally, an increasingly intrusive mass media and the growing focus in modern political campaigning on telling personal stories mean that there is now a greater openness demanded about the role of belief (and non-belief) in the lives of political leaders.

John Warhurst is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University and a columnist with The Canberra Times. This is the text of a talk he gave at the St Thomas More Forum, Canberra, on 10 November 2010.

John Warhurst is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University and a columnist with The Canberra Times. This is the text of a talk he gave at the St Thomas More Forum, Canberra, on 10 November 2010.