Every morning, my grandfather collected two bottles of milk and his copy of The Age from the front verandah, wandered down the passage to the kitchen, set the bottles on the table, and propped the newspaper against them. He then read as much as he could, starting at the front page and the headlines while eating his porridge and before leaving for work. My sport-mad father, on the other hand, read The Sun over his bowl of Weeties, but always started at the back page: for him, this was simply part of the natural order of things.

Every evening, listening to the news was compulsory, and so was household silence. Majestic Fanfare heralded the ABC for my grandparents, while my parents favoured 3DB and Heart of Oak. Now I wonder whether they believed all that they read and heard? Living when they did, they must have known about propaganda because of the two world wars. But all of them had been raised in Christian households and thus believed in the supreme value of truth. I also think they believed in trust as a value, and so trusted the government. At least most of the time. But I was a child then; what did I know?

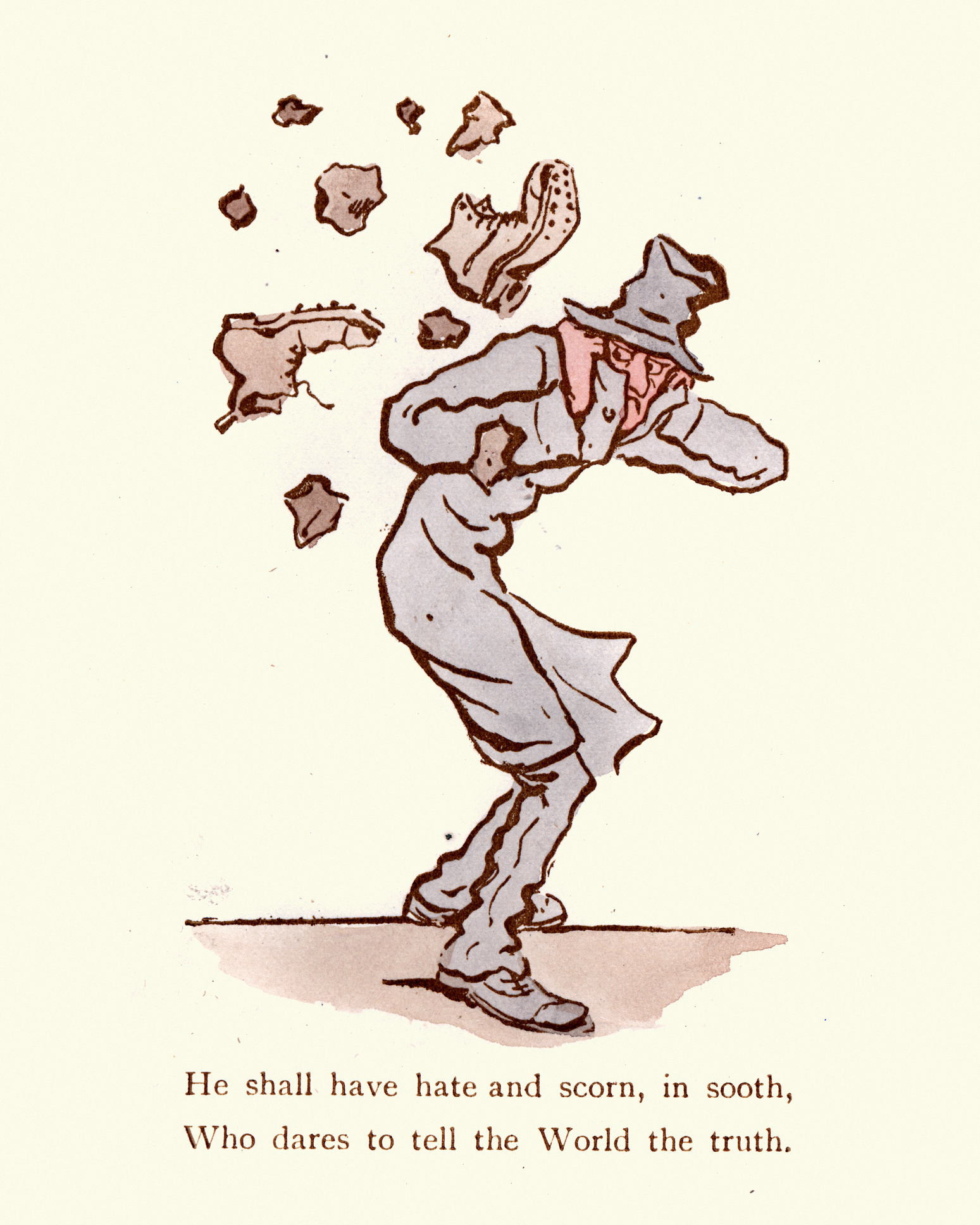

What I know now is that both trust and truth seem to be in very short supply everywhere, despite the much-vaunted emphasis on so-called transparency. Polymath Francis Bacon, whose famous essays were published in 1625, opened his writing Of Truth with the lines: ‘What is Truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.’ How canny the man was, for it turns out that the matter of truth is one of the most complex concepts in the history of philosophy: there are five basic theories of truth, I have discovered. And it was Greek playwright Aeschylus who is supposed to have first expressed the idea that the first casualty of war is truth: I wonder what he would have to say about the current Gaza/Israel conflict? Then there is the problem that individuals can have their ‘own’ truth. For example, some people still believe, despite the evidence, that Planet Earth is flat. And two thirds of Republican voters believe that Donald Trump won the 2020 election.

'Once upon a time it was fairly easy to distinguish fact from fiction, but now journalists in particular regularly merge the two.'

I recently watched the BBC’s Katty Kaye interview Anthony Fauci, the immunologist who has advised seven American Presidents, and who became world-famous during the recent Covid pandemic. From the outset, Fauci said, he made up his mind that he had to tell each President the plain, unvarnished truth, things that they might not want to hear. He relied on the available data and always tried to puncture the balloon of misinformation that was often flying high. Almost inevitably, however, he was reviled and threatened with death by various extremists who could not accept his views. His detractors seemed to think he was concocting a kind of fiction aimed at undermining President Trump.

Once upon a time it was fairly easy to distinguish fact from fiction, but now journalists in particular regularly merge the two. And when emotion, bias and prejudice take over in reporting, then truth seems elusive indeed. As for trust, how can that be maintained when politicians (and others) argue that black is white? In the UK, the latest example of this tendency is the claim made by Home Secretary James Cleverly that the backlog of asylum seekers’ applications has been cleared. But the data clearly indicates that this is not the case. When pressed on the matter, the Home Office admitted that there about 4000 cases not included because of their ‘complexity.’ One wag has commented that it is 26 miles of ‘complexity’ that has prevented him from ever winning a marathon.

I know I have written about the matter of truth before and have also quoted Bacon before; I may well do so again. Because ideas about truth keep changing, people are becoming increasingly cynical and suspicious. We are now forced to cope with notions such as alternative facts and the post-truth era. I, for one, cope badly with both, with this twisting of what I would like to be an essential and straightforward matter.

Aeschylus and Bacon. Let Shakespeare have the last word. In Henry IV, Part 1, he has his character Hotspur say: ‘Tell the truth and shame the Devil’. The play appeared in 1597, but the saying had been commonly known for at least 40 years. Four hundred and more years later, we would do well to remember it.

Gillian Bouras is an expatriate Australian writer who has written several books, stories and articles, many of them dealing with her experiences as an Australian woman in Greece.

Main image: Vintage British satirical cartoon. (Getty images)