There is nothing immoral about owning a property. If you can afford to own your property, well done. Yet only a few of the highest wealth households have full ownership of their homes, that is, they are not paying off loans to banks and financial institutions over a lifetime. The majority of what we refer to euphemistically as homeowners do not own their own houses per se. Their names appear on the documents and deeds, but this delusion is only possible with rivers of credit, and this comes with strings. Therefore, we might make some distinctions in terms of our current housing crisis. For the wealthiest amongst us, and those engaged in speculative property investing, there is no housing crisis. For Australians struggling to cope with large housing mortgages and growing household debt, they face significant challenges. For all other Australians unable to qualify for housing loans, they must rent. They not only face expensive and often unaffordable housing costs, but they also face debts, rising costs of living, and potential homelessness. To be clear, Australia has no shortage of land or housing, the issue is prohibitive cost and lack of savings.

The wealthiest speculators with access to easy credit, use housing as means for wealth creation, and should property prices go up significantly, they take whatever actions necessary to generate the most profit. If this requires selling, or buying investment properties, they will do it. Before they fully cash in, negative gearing in the tax system, will allow investors to write off costs. They are rewarded for running a business at a loss. The well-being of the tenants being used to pay down their loans, is irrelevant. All the losses will be absorbed by the tax system, while all the eventual profits will go to the investors and the banks.

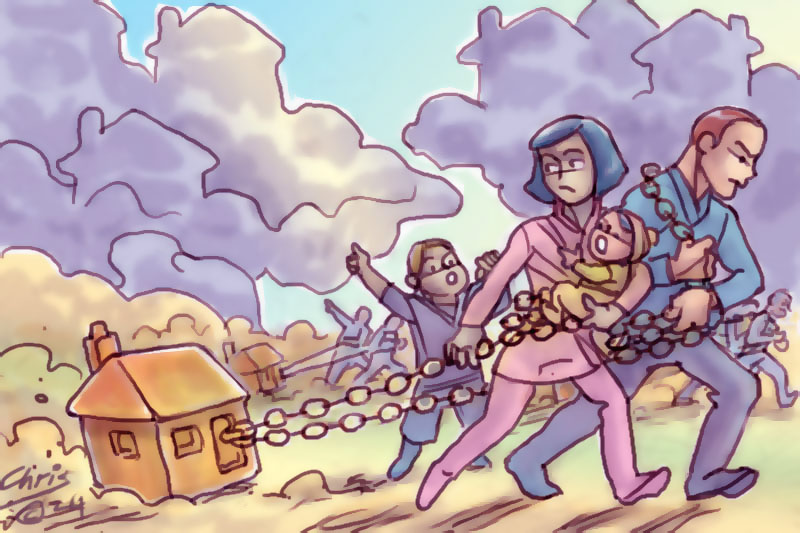

Most Australians who seek a housing loan only want some financial security and a home to raise their families. They are not interested in property speculation. This in all probability means a lifetime of potential loan repayments with interest. Once they have paid back to their creditors more than they ever borrowed, the house is theirs. Depending on their age and health, and when they enter such massive debt obligations, there is always the possibility they might not live long enough to make all the payments. Or, along the journey of being gouged by interest rates, they might default. Waiting in the wings will be those ready to profit from broken dreams.

The entire system is gamed so that only creditors and the wealthiest profit from the process. If you are rich enough to own your own home outright you avoid a lifetime of debt. It is then much easier to gain access to credit. Banks and financial institutions are always pleased to loan large amounts of money to people who clearly do not need any. If you are a speculative investor likely to generate large pots of money for your creditors as an ongoing client, you will be provided with credit. This is the world where some people can be allowed to borrow millions of dollars, invest some of the loan, and purchase property with the rest. If you make a profit well beyond what you borrowed, you will pay back your loan and pocket the rest. If you wait to sell your property, your tenants will continue to pay the rent. If you have any losses you wish to write off, the tax system through negative gearing will protect you. If your creditors think you are good for the money, there is not much they will not do to help. You are after all, paying back more than you borrowed in interest and will no doubt borrow from them again.

In contrast, millions of working Australians convinced that they must own a house do not seem to get the same flexibility with their loan arrangements. Their loans lock the recipient into lifetime mortgages. Creditors want their pound of flesh no matter how long it takes. The creditor will carefully lay out over the course of decades how the recipient will be expected to pay back more than they ever borrowed. If they default, the creditors will take the property. These clients do not get the option of taking out a loan simply to engage in speculative wealth creation because they have more limited means, they must then be gouged by interest for as long as it takes. If the recipient lives long enough to ever pay off the loan, they might have at least a few good years to enjoy the property before they drop dead.

This goes to the heart of our current housing crisis.

'Creating the possibility for ordinary people to have some savings along with affordable homes and cheaper land, will not be achieved by privileging developers, speculative finance and protecting the advantages of the wealthy.'

Housing is not seen as providing a ‘home,’ it is primarily an investment strategy that must maximize profiteering for the wealthy and creditors. In fact, in Australia, the only shortage we really have is affordable housing and land. For those Australians barely able to afford their mortgages, the dream of financial independence is fading. They ponder what will happen if they default, their growing household debts, and old age. Once out of the housing market, those that default, will probably be out for good. For those locked into renting, this is also could be for life.

Millions of Australians will not pass on any housing assets to their children. They will continue to face the threat of not having a place to live, a problem that could confront them at almost any time. They will struggle to pay high rents and costs of living. For the homeless and the most acutely disadvantaged, they will not only remain in poverty, but it is also likely their children will face similar prospects in their own lives. This will impact our society for generations.

Housing should not be a plaything of speculative finance. It is not a means of unfettered wealth creation for individuals, banks, real estate agents, or other financial institutions. The home is the bedrock of a society, the cornerstone of a community, and the catalyst for stability. We increasingly have none of those things. By entrenching housing as only a means of wealth accumulation for the few, there can be no communities and no stability. What will Australia look like in 30 years? We can make a guess based on what can be seen right now. For example, more people struggling to survive in retirement, more people struggling to pay rent, more people being crushed by mortgage debt, more poverty, and more homelessness.

A ‘good society’ is a place where housing is a springboard for social happiness and community flourishing. It is not a get rich quick scheme. The benefits of the existing housing system promote neither the greater good of the community, or the long-term health of our society. If we do not reconfigure our approach to housing, we are doomed to permanently entrench wealth at the top and endless disadvantages below. There will be little in between. It may not seem as bad as all this to those shielded from the consequences, but a weak middle class, a debt burdened working population, and endless disadvantages for the most vulnerable, is a recipe for social decline.

.png)

The entire housing system from loans, investments, and negative gearing not only needs to be re-examined, the whole philosophy of selfish profiteering at the expense of others needs to be challenged. Even minor changes could help transform the rental and first homebuyer’s market. In tenancy agreements a ‘well-being clause’ could be included to promote the idea that housing is a human right. The rental ledger should be considered here, particularly if there is an end of tenancy dispute. A rental bond should only be used in relation to deliberate and criminal damage of the property. A reasonable effort by tenants to leave the property clean and secure is more than enough. Particularly if the landlord has already collected tens of thousands of dollars in regular rent from a negatively geared investment property. If landlords make decisions that cause short or longer term financial, family and social hardships for their tenants, they should expect to provide appropriate compensations. This as a minimum should be the equivalent of 4 weeks rent.

In terms of thinking outside of the box, the government needs to consider how they could assist people locked into renting. At the end of a tenancy, tenants should get some value from their rental ledgers. If negative gearing can somehow be justified, all tenants could be compensated 25 per cent of the total amount of rent they paid during the tenancy. If they paid $40000 over a one-year lease, this would be $10,000. A five-year tenancy at $850 per week collects a staggering $204,000 in rent. The 25 per cent ‘cost of living refund’ from $204,000 would be $51,000. If the tenant wants a single payment, it should be provided to them by the ATO tax free at the end of the tenancy. If a tenant wishes to accumulate these ‘cost of living refunds’ into a single place and collect compound interest, a special account could be set up through their superannuation fund. However, unlike ‘superannuation for retirement,’ owners of these ‘cost of living’ accounts could use and access their balance when and how they wish. If individuals, couples and families end up renting for almost an entire working life, it is no exaggeration to say, they will pay over a million dollars in rent. The equivalent of a modest $500 per week over forty-nine working years (18-67) is $1,176000. Are we happy to allow investors the benefits of negative gearing, and the tenants which make the whole system possible, nothing at all?

Housing as a tool of unfettered wealth accumulation benefits remarkably few Australians. Every year the scales are tipped so blatantly from fairness and social consequences, millions of working Australians will become less secure. Many will not own homes, they will have few assets, their children will be poorer, and they will fear old age. For the most disadvantaged among us, it will be even worse. It is time that housing is seen through the prism of responsibility and social opportunity. Creating the possibility for ordinary people to have some savings along with affordable homes and cheaper land, will not be achieved by privileging developers, speculative finance and protecting the advantages of the wealthy.

It is, in short, not about profiteering at all.

Just as Medicare enshrines a principled social contract between citizens and the state in relation to health and medical treatment, affordable housing and land should be seen in a similar light, that is, a civic investment in the dignity and wellbeing of people. The goal, the creation of a prosperous nation, stable communities, and a good society.

Adam Hughes Henry is a Canberra based academic, author and musician. He is an associate editor of The International Journal of Human Rights (Taylor & Francis). In 2021, he initiated an online petition to reform the rental system. It currently has over 11,000 signatures and can be accessed here https://chng.it/4tHXwy9zpp

Main image: Chris Johnston illustration.