On a shelf in my office at home sit three boxsets side by side: the Complete Calvin and Hobbes, the Complete Far Side and The First Folio of Shakespeare (The Norton facsimile). This may seem, at first pass, an incongruous placement of the Bard. But I think there is a strain in his comedic lines that possibly would also be at the mercy of the wit of Bill Watterson and Gary Larson. Exit, pursued by a bear, anyone? Who couldn’t imagine it being in a Far Side or Calvin and Hobbes strip?

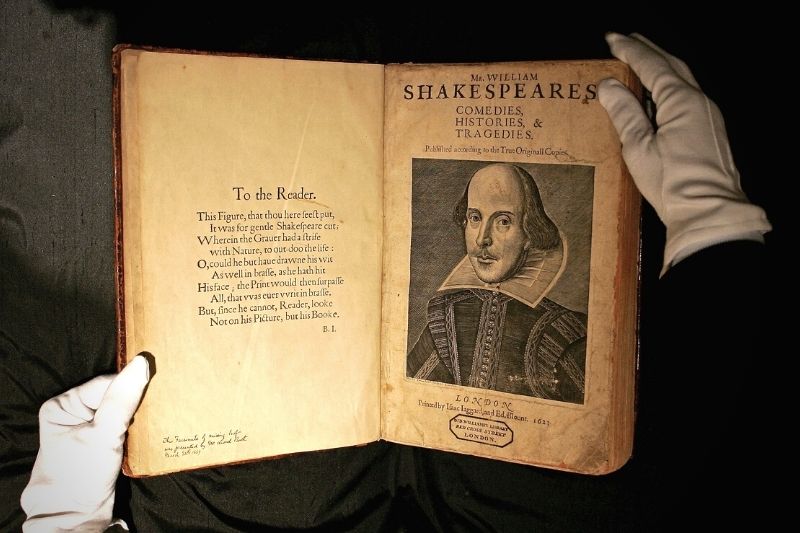

I am not a complete Shakespeareophile. A fan of his histories and tragedies, yes, but I have less ardour for his other works. It’s not him, it’s me. I have the same reaction with Bob Dylan. However, when a new edition of The Norton Facsimile of The First Folio hit the world’s stage a few years back, it just seemed necessary to own a copy. It was that impulse to just own and read the plays as people of Shakespeare’s days would have known them.

With a small leap of imagination, as I scan the delicate type, I can imagine lovers of his work 400 years ago doing the same thing. It was, and, is a transport of delight back through time. What the First Folio Facsimile is not, however, is a bedside book. A large table with sturdy legs is needed to support its weight of four kilograms (I weighed it). A tome indeed, in weight and unparalleled imagination.

The First Folio was published in November 1623. Shakespeare didn’t live to see his plays gathered together in the one place. His universe of words, his meteors of wit and description, his galaxy of human frailties and strengths, his shrouds of darkness and rays of light, were collected and bound by colleagues after his death in 1616, aged 52. The world owes them profound gratitude.

Without the First Folio, 18 plays including Macbeth and Julius Caesar might have been lost forever, for they had never been published. Shakespeare’s original manuscripts? Not a one has survived.

The Folio was the work of John Heminge and Henry Condell, who had worked with Shakespeare and were partners in the King’s Men acting company. It also displays what it is generally considered an authentic portrait of the Bard by artist Martin Droeshut.

'Despite the mountains of scholarship and publications, over the following four centuries, precious little really is known about him.'

Playwright Ben Johnson, a contemporary of Shakespeare’s, writes in the Folio of the portrait that to know Shakespeare, read his words and do not rely on appearances. Know him by his works was prescient and sage advice, for despite the mountains of scholarship and publications, over the following four centuries, precious little really is known about him.

Two centuries on from his death one who took a prodigious interest was William Hazlitt, one of literature’s finest essayist. In 1817, Hazlitt published Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays, in which he not only took apart Samuel Johnson’s criticisms of Shakespeare, but lauded his genius.

Of Macbeth, for instance, Hazlitt wrote:

‘Macbeth . . . moves upon the verge of an abyss, and is a constant struggle between life and death. The action is desperate and the reaction is dreadful. It is a huddling together of fierce extremes, a war of opposite natures which of them shall destroy the other. There is nothing but what has a violent end or violent beginnings. The lights and shades are laid on with a determined hand; the transitions from triumph to despair, from the height of terror to the repose of death, are sudden and startling; every passion brings in its fellow-contrary, and the thoughts pitch and jostle against each other as in the dark.

‘The whole play is an unruly chaos of strange and forbidden things, where the ground rocks under our feet. Shakespeare’s genius here took its full swing, and trod upon the furthest bounds of nature and passion.’

The nature and passion of humankind. The hammer may at times shape the hand, but it’s always the same blood that flows through the open palm and the fist and the same heart that pumps the blood. It’s why Shakespeare’s words live on to this day. Is there a playwright today who it could be said will be performed in 2423? (Of course, this may be a moot point given the climate’s trajectory.)

As Macbeth rasps: ‘Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.’

But this. There once was a man called William Shakespeare. What play would he make of our world?

Warwick McFadyen is an award-winning journalist. He has won two Walkley Awards and four Quill Awards. He has published several books of poetry. The latest is 21+4 Poems. His prose and poems have also appeared in Quadrant, Overland and Dissent.

Main image: A Sotheby's employee handles a copy of The First Folio 1623. (Scott Barbour/Getty Images)