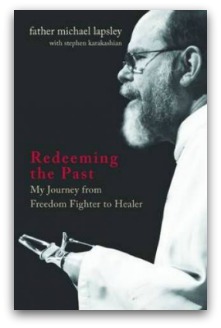

Anglican priest Michael Lapsley recently visited Australia to promote his challenging story of his ministry in South Africa and his courageous resistance to apartheid and support of the ANC. This led to his losing an eye and both his hands to a letter bomb sent by the South African security forces, and to his becoming a champion of reconciliation and healing in the Mandela era.

Anglican priest Michael Lapsley recently visited Australia to promote his challenging story of his ministry in South Africa and his courageous resistance to apartheid and support of the ANC. This led to his losing an eye and both his hands to a letter bomb sent by the South African security forces, and to his becoming a champion of reconciliation and healing in the Mandela era.

In the background of his book lie questions of how white South Africans responded to what was being done in their name, of how the few who reached out to Black Africans and pleaded their cause kept their spirits in the face of the opprobrium and ridicule they received, and of how we ourselves would have behaved.

The answers seem to lie in a strong and unwavering ethical framework and the conviction that what mattered in all their dealings with South African institutions was the human dignity of the black people whom they served.

After the passing of the recent legislation condemning refugees to indefinite detention on Nauru or Manus Island many people working with asylum seekers are asking the same questions.

The Australian situation is clearly different from South Africa of the apartheid era, but the same challenge exists to maintain morale and a moral compass when their convictions are clearly out of sympathy with the majority of their compatriots and when they are regarded as naïve or irresponsible. And they face the same perplexity in trying to act compassionately and with integrity in the new situation.

The experience of South African activists is instructive, and perhaps we have much to learn about the necessity for a strong and principled ethical framework and for a single minded focus on the human dignity of the asylum seekers themselves.

The ethical principle in play is that we may not do evil in order to achieve a good end. The end does not justify the means. In this case asylum seekers are being treated in a way that will cause them harm in order to realise goals variously described as stopping boats, protecting borders, preventing people smugglers or saving the lives of other asylum seekers. These goals may be unexceptionable, but they may not be achieved by evil means.

To inflict on other people serious harm that is unmerited, predictable and avoidable is as morally unjustifiable. The harm that the asylum seekers sent to Nauru and Manus Island will suffer is predictable and inescapable. They will be unable to move on with their lives or reunite with their spouses and families, placed in high risk of lasting mental illness, and probably restricted in their movement.

It is also avoidable. It is a choice, not a necessity.

And it is unjustifiable. It does not follow from fault or crime but is to achieve goals that have nothing to do with those sent to Nauru or Manus Island. They suffer because of the calculation that these goals will be achieved through the abuse of their human dignity.

The ethical rock on which those who serve asylum seekers must build is the conviction that the new policy in an unjustifiable abuse of the human dignity of asylum seekers and refugees. At the same time those committed to their welfare we must try to ameliorate the effects of their mistreatment. This may mean cooperating with the government to provide services that will improve the lot of people and to develop a just regional policy.

Most workers have had experience of cooperating with the government under the detention regime. It is demanding, requiring them to enunciate a clear ethical position on the policy and to avoid being coopted into its direct administration. The UNHCR has rightly refused to have any direct part in the scheme which might suggest its approval or sponsorship.

But the dignity of those suffering under the policy demands that good people provide education, foster connection with the island communities and so on and, if it can be done by Australians, alleviate some of the psychological damage caused by the indefinite sentence to languish on Nauru and Manus Island.

Lapsely's experience suggests how hard it was in South Africa to maintain a steady moral compass and so to avoid being made complicit in an unjust government policy, while reaching out to the people whose dignity was diminished by apartheid.

Australians working with asylum seekers under the new policy will face these challenges, and the even larger task of representing the claim of humanity to an Australian public opinion that has grown callous.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street.