The unfairness of the global financial crisis has been hard to miss. Greek pensioners impoverished, American home owners bankrupted, unemployment throughout the developed world soaring. And the worst that seems to happen to bankers and financiers is a loss of their oversized bonuses, and even that has not happened often.

The unfairness of the global financial crisis has been hard to miss. Greek pensioners impoverished, American home owners bankrupted, unemployment throughout the developed world soaring. And the worst that seems to happen to bankers and financiers is a loss of their oversized bonuses, and even that has not happened often.

How has such injustice been allowed to develop?

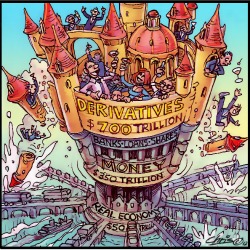

Imagine the global financial markets as a block of flats. On the first floor is the 'real' economy, the commercial exchange of goods and services. This equals about $50 trillion, with growth increasingly coming from developing economies because Europe, the US and Japan are experiencing declining growth rates.

The second floor is the conventional world of money: bank lending, shares, land, bonds. It is about $350 trillion, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.

The third floor is derivatives. These are complex financial instruments 'derived' from more conventional forms of money (that is, it sits on the second floor). It is possible, for instance, to take out a derivative, such as a futures contract, to bet on the direction of a company's shares on the stock exchange. This 'derived' trade can create much larger profits or losses than would be possible with the actual shares and may not even require buying or selling the actual shares.

The initial catalyst for the GFC was the failure of a derivative called collateralised debt obligations (CDOs). These were derived from conventional mortgages. The mortgages were securitised (aggregated into a security), and the bits sold off around the world. When things went wrong, it was realised that the CDOs were not like a normal mortgage secured against the underlying property. No-one knew what the lines of ownership and accountability were any more. That uncertainty led to a collapse of trust in the system and the crisis.

Derivatives are not new. They have long been used to hedge (price insure) commodities like wheat and pork bellies. But over the last 15 years their usage has increased dramatically. Changes initially made by US president Bill Clinton and reinforced by former US Federal Reserve chairman Allan Greenspan allowed financial institutions and traders to grow spectacularly.

The Bank for International Settlements estimates that the global stock of derivatives is over $700 trillion.

The construction of the global capital markets is thus looking a little top heavy, not to mention unstable. The third floor is twice the size of the second floor, and 14 times the first floor.

What we have been witnessing for the last four years is a desperate attempt by the governments of Western nations to reinforce the second level. Especially the portion that is bank lending, which almost ground to a halt after the collapse of Lehmann Brothers in 2008 and which has been weak since.

This in turn has created a focus on government debt, especially in Europe. Governments finally have to underwrite the banks (as they did in Australia with government guarantees of deposits and wholesale funding) and so they cannot be crippled by debt themselves.

The rush to fix the second floor has taken attention away from the real problem: the oversize third floor. An impression has been created that governments have somehow caused the crisis by being profligate, the only solution for which is extreme budget austerity. It is a simplistic picture at best.

Globally, government debt is only about $41 trillion, of which two thirds is held by the US and Japan. Private debt, consisting of financial institution bonds, non-financial corporate bonds, securitised loans and non-securitised loans is estimated at $117 trillion. And then we have $700 trillion of derivatives to worry about.

Still, the banks had to be saved and that meant using public money. The US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have been loaning banks money at virtually no cost and then encouraging the same banks to purchase government bonds at a high rate of interest (interest paid to the banks, of course). They have used taxpayers' money to subsidise the finance sector which caused the problem.

That is the kind of absurdity that occurs when you live in a block of flats that does not make engineering sense.

It is tempting to call for more aggressive treatment of financiers, and it is likely the current scandal over the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), the rate at which banks lend money to each other, will result in significant criminal prosecutions.

Yet revulsion at greed and irresponsibility is not the most important point. The existence of greed is hardly new in the finance sector. More significant is the body of quasi-scientific ideas that has led the world into this situation.

At the heart of this strange lurch into the 'meta money' world of derivatives and high speed computerised trading is the belief that money is a thing, something like water, that 'flows' around the world, reaching 'equilibrium', or experiencing 'volatility'. This can in turn be analysed much as a scientist would analyse a natural phenomena, such as the movement of the tides.

Of course, money is not that. It is transactions between people, based on trust. It enables the cooperation that forms the basis of social life. Human beings should be at the centre.

Yet that is the opposite of what is happening. Instead of money being used in the service of people, people are increasingly serving the interests of money and its high priests.

David James has been a business journalist for 25 years and is the author of Managing for the Twenty First Century and The Business Devil's Dictionary. He has a PhD in English Literature from Monash University.

David James has been a business journalist for 25 years and is the author of Managing for the Twenty First Century and The Business Devil's Dictionary. He has a PhD in English Literature from Monash University.