It is hard not to smile over Woolworths' and Coles' 'voluntary' adoption of a code of conduct. Wasting no time in gaining a public relations advantage, Woolworths chief executive Grant O'Brien joined Wesfarmers managing director Richard Goyder in urging Aldi, Costco and IGA to sign the landmark grocery code of conduct with suppliers. The code was the result of 14 months of negotiations with the Australian Food and Grocery Council. Now that the duopoly has decided to mend its ways, it seems it can occupy the moral high ground and preach to everyone else.

It is hard not to smile over Woolworths' and Coles' 'voluntary' adoption of a code of conduct. Wasting no time in gaining a public relations advantage, Woolworths chief executive Grant O'Brien joined Wesfarmers managing director Richard Goyder in urging Aldi, Costco and IGA to sign the landmark grocery code of conduct with suppliers. The code was the result of 14 months of negotiations with the Australian Food and Grocery Council. Now that the duopoly has decided to mend its ways, it seems it can occupy the moral high ground and preach to everyone else.

There is little reason for confidence. The practice of self-regulation arose because it was widely agreed that whenever governments interfere in markets it is bad for efficiency and probably counter productive. In the financial markets such a 'hands off' approach was the default position of regulators like Alan Greenspan, the former head of the US Federal Reserve, who assumed that if everyone acts in their own enlightened self interest then everything would be fine. It was not, as the GFC showed.

To see why codes of conduct do not address the problem, it is worth looking a little closer at what O'Brien said: 'All stakeholders should be well minded to keep what's best for customers at the forefront of their minds.' According to this, the ethical imperative is to serve customers' best interests. Everything else comes second.

At best, this is superficial, at worst misleading. There are many players involved in markets, not just customers. These include suppliers, employees of the companies (including O'Brien), shareholders and the general community (to the extent that it is affected by the behaviour of corporations). For the system to be robust and sustainable, which is the point of having a regulator, these different interests must be balanced.

By arguing that the only interest that matters is that of the customers, O'Brien is showing why companies are incapable of overseeing the health of a whole system. Neither will customers be able to do that. Stand in a supermarket queue and you will quickly see how much customers care about the interests of other customers, let alone anyone else in the production chain, or the wider community.

Even if self-regulation is effective (and there are many instances when it has been a sop to cover up business as usual) it is invariably too simplistic. It can be roughly characterised as: 'Customers come first so that the company can be profitable, shareholders are looked after and I meet performance hurdles and do well in my career. Everyone else we can worry about later and let the public affairs department or human resources look after it.'

It is reasonable enough that executives of corporations behave this way. The Corporations Act stipulates that boards must act in the interests of the 'company'. This is usually interpreted to mean acting in the interests of shareholders. For executives, it is largely about achieving growth in revenue, market share and profitability.

Nowhere is there anything about the interests of suppliers, who are being most disadvantaged by allowing such a dominant supermarket duopoly. Worse, it is arguably in the interests of customers to treat suppliers appallingly. By O'Brien's definition, putting the squeeze on suppliers is ethically correct. Especially when neither Coles nor Woolworths, despite their market dominance, can find greater profitability from efficiencies.

Whenever the duopoly is put under the microscope, it is concluded that their market is 'competitive' because they have tight profit margins. It never seems to occur to anyone that another possibility is that they are poorly run.

There cannot be anything in a code of conduct about the overall health of the market, especially its diversity. Unsurprisingly, corporations want to have as few competitors as possible. No code will ever include stipulations like restricting one's own excessive market dominance, which is the only change that would make any difference. An actor from outside the market has to do it, and that invariably means government.

The Western world has been subject to a quarter of a century of propaganda about the virtues of deregulation and the evils of government. The very idea of governments governing is now regarded as inherently suspicious. A barrage of think tanks, mostly funded by corporations or free market lobbyists, have spewed circular arguments demonstrating why no other views can be countenanced. Critics are subjected to insults about 'socialism' (my personal favourite was when critics of 'economic rationalism' were accused of being 'irrational', a neat circularity).

In consumer markets there is at least an argument to be had for self-regulation (in the finance sector it is contradictory nonsense). A balance needs to be struck between business freedom and regulation.

That balance needs to go much further than Adam Smith's so called 'invisible hand', the idiotic proposition that if everyone is allowed to be selfish, there will be a collective altruism (which is of course a misrepresentation of Smith). According to such kindergarten thinking, just as governments governing is inherently counter productive, so any thinking about the interests of others is a self defeating delusion. Sigh.

Finding the right balance is difficult, so governments have often shirked the issue, especially when the big corporations are involved. Instead of undertaking the difficult task of identifying and monitoring the balance of interests in markets and taking measures to ensure the system is robust, they have all too often been willing to hand it over to the participants. They have accepted that there are only two choices: bad government or no government. Good government is off the table.

Thus we are left with a code and a promise to do the right thing: self-regulation. No doubt Santa Claus will visit us, too, this year.

David James has been a business journalist for 25 years and is the author of Managing for the Twenty First Century and The Business Devil's Dictionary. He has a PhD in English Literature from Monash University.

David James has been a business journalist for 25 years and is the author of Managing for the Twenty First Century and The Business Devil's Dictionary. He has a PhD in English Literature from Monash University.

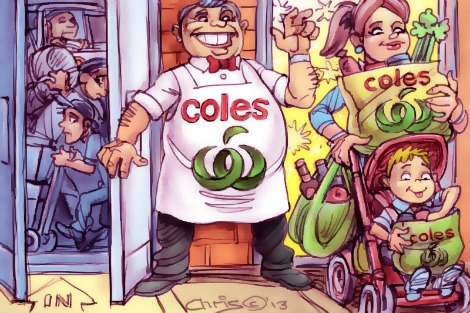

Original artwork by Chris Johnston