The stands at Ellis Park are empty and rain-flecked, the placards lie discarded, the eulogies have evaporated into Johannesburg's leaden skies. As world leaders board their private jets or slide into their first class suites and head home to their own restless constituents, what lessons will they take with them from the life of the man they had criss-crossed the world to mourn?

Not those one would have expected to have been absorbed at a gathering as unprecedented as this.

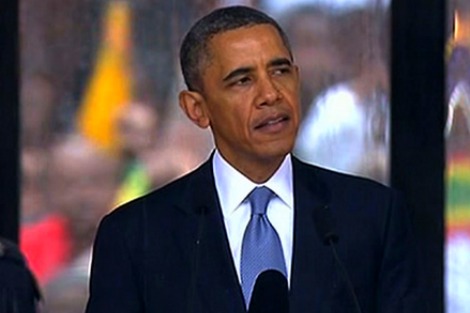

As Barack Obama rose to deliver his eulogy, few would have missed the similitude between him and the man he called a 'giant of history': the hope that each man had brought to the lives of the oppressed, their shared African roots, their equivalence in charm, physical stature and oratory skill. The anointing of Obama as Mandela's godson was manifested in the roars of approval directed at him by the gathered crowd.

People respond well to heroes, especially those people who have had their rights subjugated by others. But Obama, with his swagger and rhetoric, was basking in the reflected glow of Mandela's hard-won glory. His address fulfilled the collective expectation that the almost-saint Mandela be eulogised by a man of comparable stature, but it also afforded him a global platform on which to polish his own ego, to reinforce his importance on the world stage.

But words of praise for a great man's ability to forgive, to compromise, to see humanity in the enemy, are hollow indeed when the person uttering them fails to follow the example.

As Obama spoke, drones fell and prisoners slept through another night of confinement at Guantanamo Bay. As Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott reflected sorrowfully on Mandela's humanity, three asylum seekers lay freshly dead having tried to reach Australia, and still others prepared for permanent exile from the safety of the Australian soil they had tried so desperately to reach. As Indian President Pranab Mukherjee lauded Mandela's quest for equality, untouchables in his own country suffered the consequences of a crippling tradition of prejudice.

Only the much-maligned South African president Jacob Zuma, vulnerable on home ground, invoked the ire of his people who appreciated the true irony of his tributes.

The jollity of the occasion — the back-slapping of presidents and former presidents, the taking of selfies, the basking in admiration that had been aimed at Mandela — undermined the very legacy they were here to celebrate. It suggested that eminent leaders had used this solemn occasion to cement and celebrate their own place alongside Mandela in the global political hierarchy. As they stood on the shoulders of this giant, they should have been reflecting instead on how far they would have to go before they could match his exceptional accomplishments.

Catherine Marshall is a journalist and travel writer.

Catherine Marshall is a journalist and travel writer.