One day many years ago when I was a Pure English student at Melbourne Uni, I was chatting about difficult books with another girl who was a year ahead of me. My two stumbling blocks (mea maxima culpa) were Joseph Conrad and George Eliot. Hers was Joyce.

‘Oh, it takes a little while at first, but it’s worth it,’ I said, thinking she must be talking about Ulysses.

‘God no,’ she said. ‘I just couldn’t get into it.’

‘Try starting at the last chapter, Molly Bloom’s soliloquy. It’s great.’

‘Who’s Molly Bloom? I meant Portrait of the Artist. Just couldn’t get through it.’

I didn’t know what to say. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is one of the most lucidly expressed novels ever written, the kind of book you don’t put down because it is so gripping. How could someone doing an English major find that hard to get into? I knew Ulysses took a bit of an effort at first, but I had become entranced with it ever since Second Year English. It wasn’t on the course, but I decided that I was old enough to risk the reputed naughtiness and read it in the Baillieu Library, mystified at times, but bowled over by the torrent of meaning and language and feeling. I used a reader’s guide at the time (I think it was the one by William Tindall) and found it all wonderful – when exploring a new universe, a decent map is necessary.

After that first effort I devoured it again and have since read it many times, finding something new and profound with every revisit. So I hastened to put her right. Unwisely (I was young and silly – sue me) I indulged in a bit of skiting: ‘Portrait is really easy; I love it but Ulysses is fantastic – I’ve read it three times. It gets better every time. Really.’

My boasting, albeit truthful, was met with a smile half-pitying and wholly triumphant at having, she believed, caught me out in a foolish piece of self-aggrandising falsehood. Obviously embarrassed for me, she avoided me for the rest of the year and serve me right, I should have known better. I’m an eldest daughter and we never get away with anything, not even a bit of bragging.

'[Joyce] is able to adopt and pastiche the styles and sensibilities of other genres, other writers. He obviously read everything and anything and absorbed more than just mythology and high culture. Lowbrow stuff came as easily to him as the most intellectual discourses.'

I took comfort in others who loved him too: notably the brilliant and generous Mary Kenneally, who had been my English tutor in St Mary’s College and ever since then a dear friend. Some years ago, she rang me to ask me to fill in for her at a Bloomsday celebration that she’d had to dip out of – a spot of reading aloud with a cod-Dublin brogue to a Joyce-curious audience.

And that is how I met Frances Devlin-Glass, the heart and driving force of Melbourne’s annual Bloomsday celebration and one of the greatest Joyce scholars in the world. Since then I have sometimes taken part in the presentations and greatly enjoyed others’ contributions.

Every year, for the last three decades, Frances has gathered and delegated and inspired people to dip a toe and then dive into the greatest writer of the twentieth century. (I brook no arguments there: it’s Joyce and then all the others, rank them how you will. It’s like the Beatles: you make your top ten or top 500 lists of contemporary musicians, but they sit there, incontrovertibly the top, like Shakespeare in the playwrights, Bach in the composers and Caruso in the singers. Joyce is like that.)

Bloomsday is celebrated on the 16th of June every year around the world. That day in 1904 was special to Joyce personally, being the date of his first sexual encounter with his life partner Nora Barnacle. The entire 24 hours of June 16, 1904, are what we are given in the novel Ulysses, as we follow the man who encompasses the consciousness of our entire culture and our human needs and perceptions throughout a day and a night.

I talked with Frances about what drives the enthusiasm for Joyce and what keeps people coming back to explore more of that world. A large part of the reason why people keep coming to Bloomsday celebrations is that Frances and her cohort of experts aren’t afraid to innovate. Bloomsday in Melbourne saw them debut Joyce’s only play Exiles; it was sold out on many of its nights and reviewed favourably in The Age.

Juliette: What else is happening for Bloomsday this year?

Frances: We are doing two introductory courses in August and September. The first one is we're just taking two very different stories from Dubliners: ‘The Boarding House’ and ‘The Dead’, which is in a completely different key and it's a more ambitious novella really. The other one we decided we wanted to do is one of the metafictional chapters of Ulysses but a very accessible one – ‘Nausicaa’– and we won't just be doing The Dirty End of the chapter which is what normally happens [when people discuss it]. It moves into the area of intimate smells and the human/animal borderline. It also demonstrates the differences between male and female sensibilities and takes on the world; the first half is fascinating in the way that it blends a whole lot of different discourses: discourses taken from women's magazines, women's romantic fiction, Mariology and church liturgy.

One of the things I love about Joyce is his chameleon mode: he is able to adopt and pastiche the styles and sensibilities of other genres, other writers. He obviously read everything and anything and absorbed more than just mythology and high culture. Lowbrow stuff came as easily to him as the most intellectual discourses.

It's amazing. And of course, you know the whole of the second half of the novel is a kind of feast of parody. I think that will attract not only the novices but some of the more advanced students as well, so we'll see how we go.

I feel Joyce goes beyond parody; I always feel that what Joyce does is that he's exploring an artistic expression, even on a low level, of some deep hunger within the human spirit. In the Nausicaa chapter he basically identifies that hunger in the girl, Gertie McDowell. Joyce shows that what she wants and what Leopold Bloom wants are quite different things, although she's framed it completely in that romantic style.

(Explanation for general readers who may be unfamiliar with the book: In that chapter, Bloom masturbates by the seashore while watching a young woman, Gertie McDowell, sitting and posing self-consciously some distance away. Both characters are cognisant of what is happening, and the writing’s perceptive layers of nuance, denial and mutual need for sensuous response are detailed in ways that can be explored deeply and rewardingly. Bloom, it has to be said, is not always admirable. But neither is he evil.)

At the end he actually blows a kiss and thanks her for the mutuality of them very differently pleasuring themselves. He says thank you to her, for which I can forgive him other stuff.

It was weird that I never felt that he was abusing or exploiting her.

Well, in one of the earlier chapters, ‘Calypso’, there is a leering moment where he enjoys the swinging hams of the woman who's actually beating the carpet – I could understand beginning students of the novel thinking ‘This is not a nice chap’. It takes, I think, about twelve chapters to really appreciate Bloom, the full story. There is a kind of sensitivity to a minute sensibility that is profoundly accepting of women rather than just expositions of all of them.

That's the wholeness of the book, isn't it? In that one of the wonderful things about Joyce is that he's never doing didactic stuff.

Never. Even when he is skewering people, say for instance in Portrait of the Artist when he is skewering the cruelty with which he was treated, it's never kind of ‘do this or you'll be a bad person’; you never get that from Joyce.

And it's funny how now you find in in contemporary art there is a demand for social justice to be expressed in every line and aspect, a moral agitprop rather than a difficult truth, and it can be difficult to thoroughly enjoy a piece of current art in the way we thoroughly enjoy Joyce.

Because he sees the human comedy. What is it that saying about it – ‘comedy = tragedy+time’? The thing is that he's looking in this benign way into human nature; it's a sensibility that encompasses everything and is compassionate and can also encompass the worst kind of suffering.

Yes, people seem to get really bogged down in the scatological and sexual details that he gives, but they don't seem to be able to encompass the much broader aspects of everything that he's offering – that he understands rage, he understands the yearning of the spirit for meaning.

The other thing that he does is that he knows that rage comes out of some sort of experience … I'm thinking of probably one of the worst characters in the novel, that’s The Citizen and his most political speech, [Joyce] applying this in the same sort of manner as Shakespeare will often have a minor character, you know, spell out something that that is an important thematic.

Yes, although the most terrifying character in all of Shakespeare is Iago, I think. That’s the knowledgeable devil – he knows goodness and rejects it. I remember The Citizen in the Bloomsday production at the Melbourne university in 2012. That was ‘An Irishman and a Jew go into a pub’. You explored that and I thought that that was that was a very important thing to do. Although I think too that the governess, Dante Riordan, is a genteel version of The Citizen. When you see her in Portrait in the argument about Parnell at Christmas you see that same vicious burning rage. Whereas Stephen’s father is weeping and saying, ‘My fallen king!’, Dante is rejoicing in the idea of Parnell in burning in hell for adultery.

That's a terrifying thing too. Yes, all those terrifying stories that were told to them about hell and eternity, and the very tactile nature of the fears that they were imbued with; it's hard to forget the gruesome detail of those fears. So, Juliette, do you remember when we did Portrait at Port Melbourne in 2001 and Newman [College] again in about 2007? The Catholics had started cackling hysterically at the hellfire sermons because of their excess, you know. And the Protestants in the audience were horrified. But the Catholics were relating to memory.

How are the bookings going for the seminars this year? The good news is that it looks like more and more people are becoming interested.

We’ve got a whole lot of new enrolees. We've been doing these courses now for about 10 years I guess and there’s quite a hunger for them, which is great.

Upcoming events for Bloomsday in Melbourne with Bloomsday’s Artistic Director Frances Devlin-Glass and Joycean Steve Carey, include a seminar on Dubliners and a seminar on the chapter of Ulysses that got the book banned around the world.

Juliette Hughes is a freelance writer.

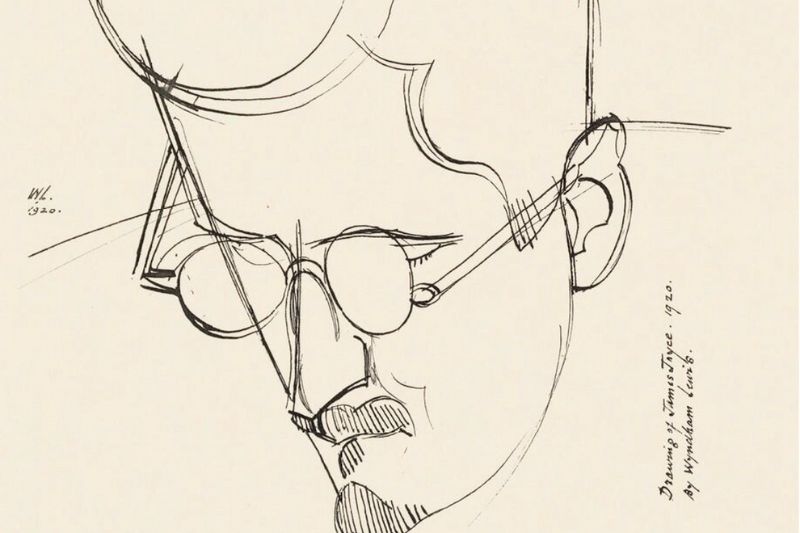

Main image: A drawing from 1920 of James Joyce by Wyndham Lewis. (Wyndham Lewis and the estate of the late Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis)