I have two points to make about Pope Francis and seven points to make about the encyclical Laudato Si.

The Pope

1. Francis makes no pretence to being a theologian in the same class as his predecessor Pope Benedict XVI. He has such humility that he would not even claim to hold a candle to John Paul II. He is not on about changing dogma or church teaching. He rightly thinks that we have had our fill of the teachings laid down from Rome; we just need a bit more old fashioned pastoral solicitude.

2. Francis is all about dialogue. The self-described Bishop of Rome exercises his primacy so as to effect dialogue amongst all sorts of people with all sorts of diverse experience and competencies.

That's what last month's synod was all about — making the space for dialogue. That's what this encyclical is about — enhancing the prospects for constructive dialogue especially when world leaders gather shortly in Paris to discuss climate change.

The Encyclical

1. The Call to Dialogue

Laudato Si is a committee job which could have done with some better editors. But it is the fruit of extraordinary collaboration. Seventeen bishops' conferences are quoted. Subsidiarity is not only espoused; it is enacted in the drafting process. Scientists, economists and political scientists all had a place at the table. The basic structure of the document is: Chapter 1: what's the problem; Chapter 2: what's scripture and the tradition got to say about it; Chapter 3: how did the problem arise; Chapter 4: what are the principles for addressing the problem; Chapter 5: what can we do about it; Chapter 6: how can we develop our own interior disposition for change.

And guess what: the key to immediate future productive action for this pope is DIALOGUE. Just consider the subheadings of Chapter 5 which asks what we can do about it. Those subheadings are:

-

Dialogue on the environment in the international community

-

Dialogue for new national and local policies

-

Dialogue and transparency in decision-making

-

Politics and economy in dialogue for human fulfilment

-

Religions in dialogue with science

He's not pretending to hand down the answers from on high. He is inviting us all to participate in a dialogue.

2. Creation, the other and the self

We are engaged in a three-fold mission, in a set of relationships with length, breadth and depth. There is nothing altogether new in the theology of the encyclical. But the pope looks to Francis of Assisi who integrates the three main aspects which need to be held together — our relationship to creation, our relationship with others, especially the poor, and our relationship with our inner being. He says, Francis of Assisi 'shows us just how inseparable the bond is between concern for nature, justice for the poor, commitment to society, and interior peace.' (#10) He says that 'human life is grounded in three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbour and with the earth itself'. (#66) He is very critical of 'a tyrannical anthropocentrism unconcerned for other creatures' and insists: 'Disregard for the duty to cultivate and maintain a proper relationship with my neighbour, for whose care and custody I am responsible, ruins my relationship with my own self, with others, with God and with the earth.' (#70)

3. No definitive answers to the big scientific, economic or political questions

Contrary to much of the public carry-on, the encyclical does not give answers to big scientific, economic or political questions. Francis insists that such answers are beyond his competence and beyond the competence of the Church. He does not pretend to have answers to the big questions which will confront world leaders when they gather in Paris. But he does think the science is IN, and the evidence is clear that much of the climate change, loss of biodiversity and water shortages are the result of human action. He thinks we have been over-reliant on technology to find the answers without our needing to amend our behaviour, and over-simplistic in our naïve hope that material progress will continue. Beyond this, he does not claim to have the answers or even the key directions in which we need to move.

Contrary to much of the public carry-on, the encyclical does not give answers to big scientific, economic or political questions. Francis insists that such answers are beyond his competence and beyond the competence of the Church. He does not pretend to have answers to the big questions which will confront world leaders when they gather in Paris. But he does think the science is IN, and the evidence is clear that much of the climate change, loss of biodiversity and water shortages are the result of human action. He thinks we have been over-reliant on technology to find the answers without our needing to amend our behaviour, and over-simplistic in our naïve hope that material progress will continue. Beyond this, he does not claim to have the answers or even the key directions in which we need to move.

Three weeks ago the New York Times columnist Andrew Revkin spoke in Brisbane at the Global Integrity Summit. He has been writing about science and the environment for more than three decades. Through his hard-hitting coverage of global warming he has earned most of the major awards for science journalism. He is no papal groupie but he reported on being one of the experts called to Rome for consultations when the encyclical was being drafted. In his Brisbane presentation, Revkin particularly emphasised this paragraph from the encyclical (#60):

[W]e need to acknowledge that different approaches and lines of thought have emerged regarding this situation and its possible solutions. At one extreme, we find those who doggedly uphold the myth of progress and tell us that ecological problems will solve themselves simply with the application of new technology and without any need for ethical considerations or deep change. At the other extreme are those who view men and women and all their interventions as no more than a threat, jeopardizing the global ecosystem, and consequently the presence of human beings on the planet should be reduced and all forms of intervention prohibited. Viable future scenarios will have to be generated between these extremes, since there is no one path to a solution. This makes a variety of proposals possible, all capable of entering into dialogue with a view to developing comprehensive solutions.

Revkin was impressed at Francis's willingness to listen attentively to all views and to weigh the evidence. The encyclical states: 'On many concrete questions, the Church has no reason to offer a definitive opinion; she knows that honest debate must be encouraged among experts, while respecting divergent views. But we need only take a frank look at the facts to see that our common home is falling into serious disrepair.'(#61)

4. Questioning the myth of unlimited material progress

Where Francis starts to get into trouble with some from the west or from the north (depending on your geopolitical perspective) is in his questioning the myth of unlimited progress. He says, 'If we acknowledge the value and the fragility of nature and, at the same time, our God-given abilities, we can finally leave behind the modern myth of unlimited material progress. A fragile world, entrusted by God to human care, challenges us to devise intelligent ways of directing, developing and limiting our power.' (#78) He boldly asserts, 'Never has humanity had such power over itself, yet nothing ensures that it will be used wisely, particularly when we consider how it is currently being used.' (#104) He is clearly at odds with those who assert that the key to the future is simply growing the pie so the poor can get more while the rich need not get less than what they already have, and that growing the pie is as good a way as any ultimately to save the planet. Francis doesn't buy this status quo position. He thinks there is a need to limit the size of the pie, for the good of the planet, and there is a need to redistribute the pie so that the poor get their equitable share.

5. The shortcomings of the market and of populist government

Hailing from Argentina, Francis puts his trust neither in ideological Communism nor in unbridled capitalism. Like his predecessors Benedict and John Paul II he is unapologetic asserting, '[B]y itself the market cannot guarantee integral human development and social inclusion.'(#109) He has not known a regulated market that works well. He has not known a polity in which all including the rulers are under the rule of law. He questions any economic or political proposal from the perspective of the poor, and he is naturally suspicious of any economic or political solution which is likely to disadvantage the poor. What for him may be a failure of the market might be seen by some of us who are used to well regulated markets in societies subject to the rule of law as a failure caused by market abuses which might be readily corrected by the application of right economic and political strategies.

For example, he has little time for the idea of a cap and trade scheme of carbon credits. He asserts, 'The strategy of buying and selling "carbon credits" can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases worldwide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require. Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors.' (#171)

Given the politics we have endured for the last seven years here in Australia, we might be more sympathetic to his critique: 'A politics concerned with immediate results, supported by consumerist sectors of the population, is driven to produce short-term growth. In response to electoral interests, governments are reluctant to upset the public with measures which could affect the level of consumption or create risks for foreign investment. The myopia of power politics delays the inclusion of a far-sighted environmental agenda within the overall agenda of governments. Thus we forget that "time is greater than space", that we are always more effective when we generate processes rather than holding on to positions of power. True statecraft is manifest when, in difficult times, we uphold high principles and think of the long-term common good. Political powers do not find it easy to assume this duty in the work of nation-building.' (#178)

6. The world is crying out for a new politics

Nationally and internationally, we need improved political engagement by our leaders who have a concern for the wellbeing of the planet and the wellbeing of all persons, including the poor. We need to get beyond short term political cycles in which elected leaders are simply populists serving sectional interests which guarantee their election. He says, 'What is needed is a politics which is far-sighted and capable of a new, integral and interdisciplinary approach to handling the different aspects of the crisis.' (#197) He sees a need for the politicians and economists to enter into dialogue for the good of all of us: 'Politics and the economy tend to blame each other when it comes to poverty and environmental degradation. It is to be hoped that they can acknowledge their own mistakes and find forms of interaction directed to the common good.' (#198) Like his predecessors in the papacy, he probably has a very idealistic hope in the UN or its successor noting, '[T]here is urgent need of a true world political authority.' (#175) He knows that the real crunch will come in Paris with world leaders trying to work out what is equitable and workable in distributing the costs for carbon consumption amongst nations which include those now wealthy because of past pollution and those now seeking to develop and lift the poor from their misery with energy efficient development. One big difference at Paris over Copenhagen will be that the Chinese will no longer be asserting that cheap polluting energy is the key to releasing 1 billion people from the clutches of poverty. They are choking in their own smog in their large cities. They know there has to be a better way.

7. Each of us needs serene attentiveness

We have to be in this struggle for the long haul. It requires a 'serene attentiveness'. He is 'speaking of an attitude of the heart, one which approaches life with serene attentiveness, which is capable of being fully present to someone without thinking of what comes next, which accepts each moment as a gift from God to be lived to the full.' (#226) We need to walk gently upon this earth while maintaining the hope that we can create the universal awareness of the need for change so that our politicians will model laws and economic regulation to ensure better behaviours enhancing the wellbeing of the planet and the poor. We should not be looking for the silver bullet or for the definitive checklist of change. We should always be acting and responding with prudence, justice and empathy. Recently at the UN, this pope with serene attentiveness showed that he knew much more than his prayers when he intimated to the world leaders that the newly minted sustainable development goals were likely to miss the mark. He demonstrated his canniness and his avoidance of glib solutions to big economic and social questions. He was even prepared to challenge the UN for being too idealistic and starry eyed. He told them:

'The number and complexity of the problems require that we possess technical instruments of verification. But this involves two risks. We can rest content with the bureaucratic exercise of drawing up long lists of good proposals — goals, objectives and statistics — or we can think that a single theoretical and aprioristic solution will provide an answer to all the challenges. It must never be forgotten that political and economic activity is only effective when it is understood as a prudential activity, guided by a perennial concept of justice and constantly conscious of the fact that, above and beyond our plans and programmes, we are dealing with real men and women who live, struggle and suffer, and are often forced to live in great poverty, deprived of all rights.

To enable these real men and women to escape from extreme poverty, we must allow them to be dignified agents of their own destiny. Integral human development and the full exercise of human dignity cannot be imposed. They must be built up and allowed to unfold for each individual, for every family, in communion with others, and in a right relationship with all those areas in which human social life develops.

This is the wisdom of someone who cannot be parodied as an anti-capitalist greenie. We are blessed to have a pope who speaks to all the world about the prudence, justice and empathy required so that more people on our planet might enjoy integral human development. He invites us to live the ecological vocation of justice — in the footsteps of Francis of Assisi, and being prepared to engage with all comers anxious about the future of the planet and the plight of the poor.

Fr Frank Brennan SJ, speaking at North Sydney and Mosman Parishes, 4 November 2015.

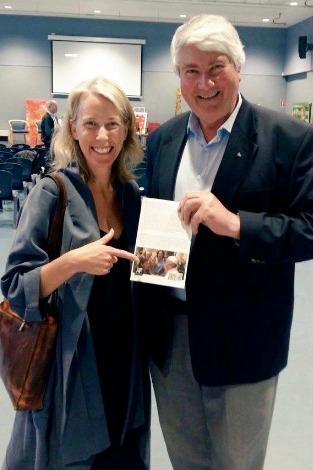

Post script: It was a delight to to speak about Laudato Si on the same platform with Jacqui Rémond [pictured with Fr Brennan], Director of Catholic Earthcare Australia. She features on the back cover of my new book The People's Quest for Leadership in Church and State, meeting the Pope together with Tomas Insua, global coordinator of the Global Catholic Climate Movement and Allen Ottano, coordinator of the South African Catholic Environmental Youth Network.