On Anzac Day I used to watch my father proudly march in the parade in our little town. Eyes forward, back straight, medals on his chest. His eyes may have been looking straight ahead, but perhaps they were also looking into the future and back into the past. He was the RSL president for the local group. I would take the kids when they were young to see him march the 50 or so metres to the town’s war memorial, where the names of those from the area who had fought and died in Australia’s war were engraved on the stone.

Once he took them hand in hand, too, to march. For that was what the commemoration meant to him, the sacrifice of war was for the kids, to hopefully allow them a better and brighter future.

My father died just over a decade ago. The ranks of those who have fought in war for this country must of time’s necessity, dwindle. The veterans of the two world wars now have gone. (Dad was in the navy in the Korean War and was part of the international force despatched to Japan after the two atomic bombs were dropped.)

The necessity of war, however, despairingly, never dwindles.

Last year’s edition of the Global Peace Index from the international think-tank the Institute for Economics and Peace showed almost 250,000 people died from conflict globally. And conflicts were being more interwoven, or more bound up country to country with ‘with 91 countries now involved in some form of external conflict, up from 58 in 2008’.

Of course these figures are but a sliver of the casualties from the two world wars. Estimates range for World War II from 35 million to 60 million, and for the First World War, about 25 million. It is hard, nigh impossible, to fully comprehend this industrial scale of slaughter. Imagine every man, woman and child in Australia dying in four years. That’s the scale of death for WWI. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the British Army sustained 57,000 casualties.

For the fledgling nation of Australia, (pop. fewer than 5 million) more than 400,000 enlisted in WWI and about 60,000 killed. From Victoria, 89,000 served overseas; 19,000 died.

'How about truth as an antidote to war? And there’s the rub. Who would have stomach for it, though we see war as part of existence?'

Each Anzac Day these ghosts move further away from us. We may say lest we forget, and continue the rites of memory, but the thread stretches ever thinner.

This is, however, also a good thing. But is it a move towards permanence of peace in our society? History would suggest not. Philosopher A.C. Grayling wrote in War An Enquiry that ‘the idea of war is a too accepted – too thoughtlessly accepted – feature of the very idea of the state and its behaviour. Instead of war being seen as an occasional bitter necessity, its mere possibility is a permanent presence in the budgets, decisions and attitudes of states. Deinstitutionalising the idea of war means changing this assumption. This task in turn requires another.

‘War is romanticised in novels, films and television programs. War is cosmeticised; television news broadcasts do not show the blood and guts. The millions watching their television screens do not see the full ghastly reality of what is happening – what their own governments might actively be encouraging, for example. Even those films that portray the horror of war are avidly watched and enjoyed because there is romance even in the horror and danger, and both are vicariously enjoyed. Vicariously because they would not be enjoyed in reality.’

Imagine if reality television were true to its name. The reporting on television of the Vietnam War had a large impact on the attitudes of Americans, and Australians, to the war. Though it was not uncut footage, it was the shock of immediacy. The shock of the old as the shock of the new.

Grayling posits this: ‘How about the aversion therapy of truth – mangled bodies, blown apart children, blood running into gutters, people screaming in pain or terror. How about truth as an antidote to war?’

And there’s the rub. Who would have stomach for it, though we see war as part of existence? The trouble with its normalisation, such as in games, both in backyards and in cyberspace, is that becomes uncoupled from reality.

World War I poet Siegfried Sassoon wrote many blistering, evocative and emotional works on his time on the battlefields. Not as famous as many of his other poems, nor that of fellow soldiers and poets such as Wilfred Owen, Sassoon’s ‘Suicide in the Trenches’ is searing in its damnation of war.

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

War is hell. The American Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman is reported to have first uttered it more than 150 years ago. It was before he said it and is still so.

Perhaps on Anzac Day as the words sacrifice and country are fluttering in the wind, we should say what every war knows, I am hell.

Warwick McFadyen is an award-winning journalist. He has won two Walkley Awards and four Quill Awards. He has published several books of poetry. The latest is 21+4 Poems. His prose and poems have also appeared in Quadrant, Overland and Dissent.

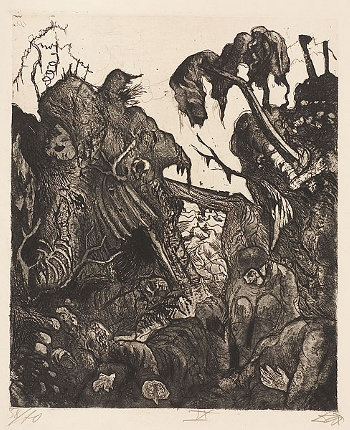

Main image: Collapsed trenches (Zerfallender Kampfgraben) by Otto Dix, 1924. (National Gallery of Australia)