I am honoured to be invited to break the champagne bottle over this book. It's had more launches than Dame Nellie Melba had farewells. That's the way of it these days. You write the book then you have to flog it. This book is well and truly worth flogging.

Frank is acknowledged as a living treasure not only because of the work he has done in the market place of ideas but because of his service to the work of justice in our nation.

Frank is acknowledged as a living treasure not only because of the work he has done in the market place of ideas but because of his service to the work of justice in our nation.

Welcome Frank back to Canberra. Many of us worried he mightn't want to come back after the high life at Boston College, one of the most prestigious of the Jesuits' academic institutions worldwide. Glad to say we don't have to worry how we'll keep him on the farm after he's seen Paris!

Which book? I thought it was: No Small Change: The Road To Recognition For Indigenous Australia. So I started to do some homework on it. I was alerted to Professor Marcia Langton last week disagreeing with his prescription.

The publisher Hilary Regan told me it was another book I was to launch. I knew Frank was prolific, so I said, 'Okay, nothing lost by having read the other one.' Amplifying That Still, Small Voice is a collection of essays, speeches, sermons and lectures, some going back ten years.

Nothing is spared the Brennan purview: his church's struggle to come to terms with contemporary realities, matters of life, death and love in all its expressions.

This book is a testament to the Brennan mission. In the introduction, Irish poet Seamus Heaney on the 60th anniversary of the UN Declaration of Human Rights speaks of the Declaration as a 'still, small voice' — the equivalent of a gold standard in the monetary system, reminding nations of the obligations they have signed up to.

The 'still small voice' is certainly amplified by Fr Brennan with courage and conviction. He is not afraid to hold his church, his society and indeed the community of nations up to the gold standard of the dignity and freedom of the individual.

But his baseline, not surprisingly as a Jesuit priest, is his belief that God is to be found in all things and we are called to discern this presence in the life of every person. This faith dimension affirms that at its base, reality is founded on, rooted in God.

This leads him to be, as Paul Keating lamented during the Wik native title negotiations, 'a meddlesome priest'. This God is not an absent God but found in every human person. Frank has found a champion in another Jesuit called Frank: the Pope who is quoted in the book saying:

A good Catholic doesn't meddle in politics. That's not true. That is not a good path. A good Catholic meddles in politics offering the best of himself so that those who govern can govern.

Pope Francis goes on to say: 'and offer prayers'. And heaven help us, those who govern this nation could do with plenty.

In discussing Australia's asylum seeker policies Frank laments the government's deaf ear to calls from the churches, his own included, for a greater measure of compassion and a better way of dealing with the issue of boat people. Frank wryly comments: 'If only the Abbott Government with its disproportionate number of Jesuit alumni cabinet ministers could listen.' Here he suggests a better way forward with a more genuine engagement with the region.

And for those who think Australia is in breach of its human rights obligations, with his lawyer's hat on, he has a sobering analysis of the limits of the international covenants. Narrow legalism won't save our humanity; meddlesome priests and people of good conscience might.

He asks in what circumstances are we entitled to be cruel to the person on our doorstep, the boat person who has risked their life to be here, so we can be kind to the person defined as being in greater need on the other side of the world. Taking my cue from this, why should hypothetical boat people have more rights that those we have locked up and treat so cruelly, so abominably on Manus and Nauru?

And in a week where the President of the Human Rights Commission, Gillian Triggs, has warned that expansion of ministerial powers is a growing threat to democracy, the chapter on pursuing human rights is illuminating.

Frank's good friend Kevin Rudd, who used to ring him up in the middle of the night to go for a walk around the lake, described Frank as 'an ethical burr in the nation’s saddle'. Rudd assigned him an almost impossible task. Frank was appointed chair of the National Human Rights Consultation to suss out the need for and the possibility of a federal Human Rights Act or Bill of Rights.

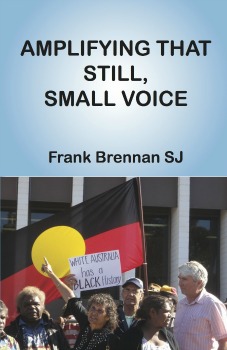

The picture on the front of the book that has the whitest of white fellas towering over black fellas protesting in Kalgoorlie was taken when his panel was seeking submissions in the West. Their visit happened to coincide with the coronial inquest into the death by heat exhaustion of the Aboriginal prisoner, Ian Ward. Frank advised his panellists to stay out of sight.

His solidarity with the placard that 'White Australia has a Black History' was a moral imperative for him, especially as one of the protestors had recognised him and called him over. The image was too controversial to put on the cover of the Consultation report. There is no such shyness here. You have much more freedom when you write your own book. It neatly sums up Fr Brennan's willingness to amplify the call to justice, recognition and reconciliation.

A ten year old speech in Oxford for Amnesty International is a useful reminder of how intractable is the debate over formal recognition of the place of Indigenous people in our nation. The context was the recognition of land rights but the arguments raging then are still being plied today. Frank divides the antagonists into realists, liberals (not capital L liberals) and idealists. He probably fits into all camps depending on the arguments.

In fact in his book No Small Change the realist is on display on how we could achieve recognition in the Constitution which he applies without allowing his idealism to be extinguished.

Two thoughts from that lecture are worth pondering as the build-up to a recognition referendum looks increasingly fraught. Paul Keating's Redfern speech: 'White Australians must start with an act of recognition. Recognition that it was us who did the dispossessing.' And the insight of novelist, Tim Winton: 'The past is in us and not behind us. Things are never over.' That certainly applies to the history our nation just as much as it applies to the history of ourselves.

In the last chapter of the book, Frank takes us on a fascinating journey. On display is his openness to review a position, to be convinced by changing realities and to apply what Christian respect really means in a secular, pluralist society. Entitled 'Espousing Marriage and Respecting the Dignity of Same Sex Couples', this chapter traces his position over four years from his acceptance of civil unions but not same sex marriage all the way through to concluding, in light of legal developments here but particularly in the United States, that the time has come for recognition of gay marriage.

It is time, he says, to draw a distinction between a marriage recognised by civil law and sacramental marriage. It is also time to accept, as Pope Francis does, the dignity and reality of gay people and their desire for love and commitment.

That brings me to some final thoughts. Amplifying That Still, Small Voice of conscience will seem to many a no brainer. But it is historically contentious, even dangerous. Many senior clerics in our church, Pope Emeritus Benedict and Cardinal Pell seem locked in a counter reformation paradigm.

Seven years ago, Fr Brennan challenged George Pell's narrow view of conscience, so narrow as to render it non-existent in the face of the church's magisterium. That book was called Acting on Conscience. What was argued there is as valid now as it was then.

Now Frank's namesake, heading 'the Firm' as Fr Bob McGuire calls the church, has lent his weight. The Pope is quoted telling the Council of Europe:

Truth appeals to conscience which cannot be reduced to a form of conditioning. Conscience is capable of recognising its own dignity and being open to the absolute, it thus gives rise to fundamental decisions guided by the pursuit of good for others and one's self. It is itself the locus of responsible freedom.

Echoing down the centuries is Martin Luther: 'Unless I am convinced by scripture and plain reason ... I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.'

This book, particularly the chapters on the church, are a courageous witness to the primacy of conscience, open to truth and expressed in love. That Frank Brennan can do it in no small way is due to the protection afforded to him by being a member of the Society of Jesus. Our church in the years of the papacies of John Paul II and Benedict condemned freedom of expression and imposed a strict and narrow orthodoxy in a punitive and in many instances an unjust way.

Now under a new papacy, time are changing. The German bishops are alert to a new openness and frankness. Frank quotes from the German bishops' response to the papal invitation to plumb the attitude of Catholics. Unlike the Australian bishops, the Germans published their findings:

In most cases where the church's teaching is known, it is only selectively accepted. The idea of the sacramental marriage covenant, which encompasses faithfulness and exclusivity on the part of the spouses and the transmission of life, is normally accepted by people who marry in the church. Most of the baptised enter into marriage with the expectation and hope of concluding a bond for life.

The church's statements on premarital sexual relations, on homosexuality, on those divorced and remarried, and on birth control, by contrast, are virtually never accepted, or are expressly rejected in the vast majority of cases.

Frank is not sure that the broader church or the synod will have an appropriate response. Especially in the latest documents released from Rome. He says:

For the moment, I would not see much pastoral point in sharing this document with the many young people I know who are living together, or with those who are gay or lesbian seeking a homecoming in the church, or with those who have endured the pain of divorce and the moral angst of remarriage. I think I will be telling them to keep the door open, wait a while and check back in a year to see how we are going.

He expresses the hope that all bishops conferences would follow the lead of the Germans.

In the book Frank's burning anger at the unjust treatment of Bishop Bill Morris comes through. If you read his views, I'm sure your own anger will be ignited. Frank Brennan's challenge to the church is summed up in this clarion call:

The church of the 21st century should be the exemplar of due process, natural justice and transparency — purifying, strengthening, elevating and ennobling these riches and customs of western societies.

These are values that the church itself fostered but so often falls short of implementing. So with these revolutionary thoughts, I declare the book formally launched on Lake Burley Griffin.

Paul Bongiorno is an Australian political journalist, formerly with Network Ten and now a regular contributor to The Saturday Paper. The above text is from his launch of Fr Frank Brennan SJ's book Amplifying That Still, Small Voice at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture, Canberra, 8 June 2015.