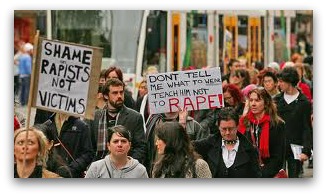

Slutwalk is back. Tomorrow, the Australian expression of this international movement will see — according to the organisers' press release — local women and men march the city streets of Melbourne to 'take a stand against rape culture' and condemn 'victim-blaming and slut-shaming'.

Slutwalk is back. Tomorrow, the Australian expression of this international movement will see — according to the organisers' press release — local women and men march the city streets of Melbourne to 'take a stand against rape culture' and condemn 'victim-blaming and slut-shaming'.

That sexual assault has in recent times been justified and trivialised by American and British politicians, lame comedians, and professional footballers may well have a mobilising effect, resulting in a larger turnout than last year's inaugural event.

It may be a reflection of my current occupation — married 35-year-old full-time stay-at-home mother — but I have very little direct experience of the social dynamics that are provoking such outrage. I haven't seen what's happening on city streets at night or worked in an office for years. That my daughters are only three and one respectively means they have (hopefully) at least a decade before anyone starts flinging the insult 'slut' at them.

I remember as a teenager having 'Ugly dog!' and 'We want some pussy!' shouted at me from moving cars, and receiving regular enquiries of 'How much?' as a 20-something St Kilda resident walking home with my groceries.

But now, aside from reading press reports of increasing sexual activity among teenagers, the prevalence of porn, the bringing of sexual harassment suits against sleazy bosses, and the continuing difficulty of bringing rapists to justice, I feel insulated (with some relief, to be honest) from the issues many women deal with daily.

I'm at a loss to know what, exactly, 'rape culture' is. Who, aside from the high profile figures perpetrating or justifying sexual assault and harassment, are the 'shamers'? And who are the 'sluts' being shamed?

While I admit to being out of the loop, as a gender historian, I am familiar with some 100 years worth of past incidents involving the abuse of Australian women and girls. Consequently, when I first read about the emergence of Slutwalk I was instantly reminded of a 1954 article I once came across in a local scandal rag.

The reporter had interviewed several women who declared themselves victims of 'lecherous' 'foreigners'. Walking home from their jobs in lowly paid clerical and factory jobs, these women reported being accosted and harassed by men in Melbourne's inner north. The men were 'flashily-dressed street wolves ... lonely, pleasure-seeking New Australians who live in the hundreds of rooming houses in the Carlton area'.

'It is a shocking state of affairs and should not be tolerated but the district is now overrun with New Australians who regard it as their own territory,' complained one woman. The paper warned women that to be 'alone and attractive courts molestation'.

Italian and Eastern European migrant men were commonly accused of harassing Anglo-Saxon women (as well as running prostitution rings and plying teenage girls with cocaine). The government's post-war migration policy favoured single men as a labour supply source for the burgeoning heavy industries. By the mid-1950s thousands of lonely male migrants were notably present in the cities, and many local-born women found them threatening.

The article fascinated me because it documented — in salacious, sensationalistic language — friction between new migrants and lowly paid young women in a working class suburb.

In the same year, an Australian Gallup Poll revealed that opposition to the migration intake was highest among small business owners, farm workers, unskilled and semi-skilled workers. As historian John Murphy notes, because migrants were automatically assigned to labouring jobs, 'the Australian-born working class most experienced social change as a result of migration'.

For Carlton women that meant — according to the article — being relentlessly propositioned by 'foreign' men. The situation equated to a turf war: who had priority use of the suburb's streets? Local-born Anglo-Saxon women or male migrant intruders?

Like those women, Slutwalk participants defend their right to walk the streets day or night wearing what they want without being harassed or worse. They do not, however, identify certain groups as perpetrators; they are keen to avoid accusations of racism and snobbery. Nor do they argue that some groups are more vulnerable to assault and abuse than others (which could, in effect, patronise such victims for 'lacking agency').

To specify that certain men are victimising certain women would also disregard the prevalence of women 'slut shaming' each other — which surely has as significant an impact on gender equality as any male activity.

While seeking not to stigmatise, the Slutwalk movement's objectives can seem nebulous and confusing. To truly change behaviours, frank discussion of the economic, political and historical factors fuelling 'slut shaming' should be welcomed. Do widening class disparities, resentment between ethnic groups, and the continuing inroads women make into once male-dominated public roles provoke the kind of misogyny Slutwalk rails against?

Beyond the evocative placard slogans ('My clothes are not my consent!'; 'End victim blaming!') some cold hard analysis of who is doing what to whom should be welcomed. Then, maybe, people like me can gain a better understanding of what exactly Slutwalk is all about.

Dr Madeleine Hamilton is an historian and the co-author of Sh*t On My Hands: A down and dirty companion to early parenthood.

Dr Madeleine Hamilton is an historian and the co-author of Sh*t On My Hands: A down and dirty companion to early parenthood.