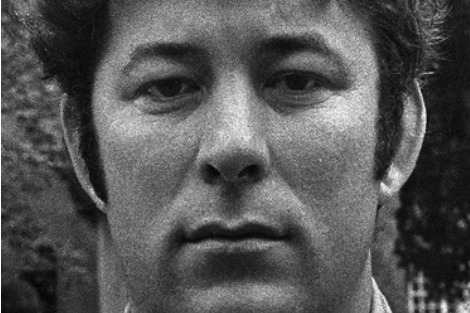

Requiem for a poet

('... who has made the room — and kept going')

When you account, as you must, the courtship with the soil,

It is a grand reckoning, croppies and trouble-makers, friends in toil,

Old fermentations, and even family in the chain of ancient moil.

We know you read the turf better, spadefall concision,

Oh! Seamus, Seamus, you could cut with such love and precision,

Make songs rise from the deep, give voices to buried vision.

Noli or nolle timere, who cares?, for it doesn't matter at all,

With the earthed and unearthed, you kept us all in thrall,

Perfecting the geology of the spirit, earth knows how to speak in Donegal.

You have been our host, high-held, so much giving, gravelly and gritty,

Inviting us in — and how exhausting! — with the richness and ripeness of festivity,

Glory be to the peat and to the bog, and to the light on The Strand in the city.

And so now the ground opens for yet another honoured guest,

You have made room and rhyme enough for us all to be blessed.

Peter Gebhardt

Getting it Right

In gratitude to Seamus Heaney

i.

In our baronies of childhood

we lived twenty miles apart,

perhaps half an hour

for the gales from the West

that shook your father's trees

to rock our copper-beech,

or no time at all

for my fingers following

our Six Mile Water

to cross Lough Neagh's

petrifying deeps

and meet your Moyola

in the River Bann

famous with eels.

ii.

But we were not to be friends,

not if you'd been our neighbour.

A James? Perhaps, but not Seamus.

I was brought up to become

a Scottish Protestant boy

in exile from the country

that was my father's homeland.

You grew up to be at home

in your history and tongue;

my father banned your accent,

set me to Elocution, as if

your speech was my speech-defect.

Our history lay elsewhere,

even as we were living it,

iii.

for I too was growing to know

your horse-powered harvests, the crex-crex

of corncrakes among the stooks,

the stench of retting flax

over crannog and souterrain,

and The Twelfth of July's bullying

yammer of Lambeg drums.

Years later then, transplanted

to this far side of the world,

when first I found your words

I knew my childhood's landscape

in your people, your place-names,

and learned for the first time

how we'd failed to make it our home.

iv.

One image: when I was seven,

we watched from an upstairs window

the flax mill on fire in the village

my father with authority

pronounced to rhyme with 'dough':

Doagh. But your voice tells me

I need remember only

the guttural that closes loch —

one sound we Scots always knew

'strangers found difficult to manage'.

While this fire burns in my mind

I'll speak it with your voice:

Doagh. Getting this right at least.

Never friends, I'll not be your stranger.

Alan Roddick

Vale Seamus Heaney

Shaken by a distant quake

whose tremors travel underground

to rattle cups and saucers on the kitchen bench:

a colossus in his land,

a granite-featured sage, has gone –

a farmer's son from County Derry,

poet for his age, our own.

Season after season he would work

his earth, the deep, rich loam,

trusting in the sureness of his hands.

Jena Woodhouse

It Matters How We Go

for Barry Lopez

How important it must be

to someone

that I am alive, and walking,

and that I have written

these poems.

This morning the sun stood

right at the top of the road

and waited for me

–Ted Kooser 'How Important it Must Be'

A siren goes by me now;

The day is over-ripe on the vine, and the wind is working hard

To pull the whole thing to the ground. The dog

Sleeps beside me — inside, out of it —

And my mind runs back to yesterday, when things stood still, and to the lighted woods.

It matters how we go and where, and how we lift our feet;

Each life seems to count among

The trees.

For acacia, and bracken fern, and ribbon gums were all over Hammock Hill again

In sun like a backburn barely in hand, and they were suffering

Grass parrots to come like children among them,

When I walked there after lunch, trailing my impossible life behind me. I carried on

A shy conversation with you, Seamus Heaney, so soon

Gone, and some I love who are living yet,

But not especially well. I worried; I drafted emails; I fashioned elegies and ripostes;

I wandered all over my head. Up and down the hill

All the while, the dog tried, as if it were

Not an ancient trick,

The patience of every rabbit inside the undergrowth until there was no more

Patience left anywhere to lose. A tree is sunlight stilled

And grown tall. A tree is water

Divined; rain born again and sluiced fast through vast dark fields, slung wide

And far in vatic flumes. A tree is spirit become matter,

Become spirit again. The canopy, a loose

And elevated encampment of song. Imagine your soul, then, as timber; your mind meta-

Morphosed to myrtle; your life a forest of thesis and chant. Walking here,

Among elders, makes a garden of me; I am curated,

Tended and conserved; walking

Is a prayer the trees seem disposed to answer sometimes: putting in the downtime

One never takes time to take; dancing out in perfect stillness the steps one falls out of,

Otherwise. And minding very quietly how one goes.

Mark Tredinnick

Peter Gebhardt is a retired school principal and judge. His most recent book is Black and White Onyx: New and Selected Poems 1988–2011.

Peter Gebhardt is a retired school principal and judge. His most recent book is Black and White Onyx: New and Selected Poems 1988–2011.

Alan Roddick is a retired public health dentist living in Dunedin, NZ.

Alan Roddick is a retired public health dentist living in Dunedin, NZ.

Jena Woodhouse's publications include two poetry collections, a novel, Farming Ghosts, and short story collection, Dreams of Flight.

Jena Woodhouse's publications include two poetry collections, a novel, Farming Ghosts, and short story collection, Dreams of Flight.

Mark Tredinnick is a winner of the Montreal Poetry Prize, and the author of The Blue Plateau, Fire Diary, and nine other acclaimed works of poetry and prose. He lives in the NSW Southern Highlands.

Mark Tredinnick is a winner of the Montreal Poetry Prize, and the author of The Blue Plateau, Fire Diary, and nine other acclaimed works of poetry and prose. He lives in the NSW Southern Highlands.