Frank Brennan's nieces Shannon and Kateena helped launch his latest book, Amplifying That Still, Small Voice. Their speeches are presented below.

SHANNON [Brisbane Launch]

Thinking about thinking

Nine years ago Frank launched another of his books entitled Acting on Conscience. At that time I was both honoured and petrified to be asked to give an address at the Brisbane launch. On the day of the launch I was in the final weeks of my first pregnancy and desperately hoping that the process of childbirth would spare me the pain of speaking publicly. It was not to be.

The child in question was Liam — who is now eight years of age. He now stands beside me. He is the namesake of a child to whom Frank so poignantly dedicated his book No Small Change, and to whom he refers, saying:

The child in question was Liam — who is now eight years of age. He now stands beside me. He is the namesake of a child to whom Frank so poignantly dedicated his book No Small Change, and to whom he refers, saying:

We all know that one of the strong inspirations for Miriam [Rose Ungunmer] wanting to establish this Foundation was the death of her beloved nephew Liam aged just 22. The world knew Liam's face as a baby but the world knew little of his story thereafter. As a baby he evinced the warmest expressions of love and admiration from strangers across the globe who saw him on their television sets ...

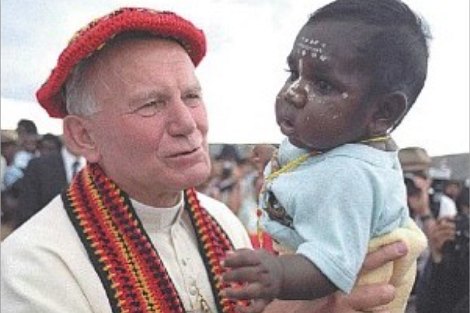

In November 1986, Pope John Paul II came to Alice Springs, met Aboriginal People from across Australia, walked the dreaming track, donned the Aboriginal colours of black, red and yellow, and then help up baby Liam handed him by Liam's mother, Louise. The photo became an international icon.

Coming into adulthood, Liam found himself all alone with nowhere to go, nowhere to belong and nowhere to be held — Miriam knows that Liam's journey has been travelled in far too many Aboriginal families.

And so, we pause to acknowledge that in Australia too many of our young people represent that small voice. These are the voices to which I wish to attend to tonight — those that are not always amplified and are at times, muted.

At present I have the good fortune of performing a locum school guidance counsellor role at a Brisbane, Catholic high school. This school is renowned for giving young people from divergent backgrounds second chances in a context where the term inclusivity is more than lip service.

About two weeks ago I was observing a young male student who had been tasked with sourcing and explaining a quote of his selection to the group of students ranging from 12 years to young adulthood. I will now ask my son, Liam, to read the quote shared by this young man:

Liam:

Watch your thoughts, for they become words.

Watch your words, for they become actions.

Watch your actions, for they become habits.

Watch your habits, for they become your character.

Watch your character, for it becomes your destiny.

I introduce this quote in this forum because I feel that Amplifying That Still, Small Voice challenges us to go right back to the beginning and think about our thoughts — to think about thinking.

Young people

Amplifying That Still, Small Voice welcomes the uplifting effect of the papacy of Francis. Very early in the book we are informed that Francis was aged 36 years when he was made Jesuit Provincial. Last week I turned 36 — Frank never forgets my birthday, which I am sure has nothing to do with the fact that it falls on the same date that the Mabo judgement was handed down!

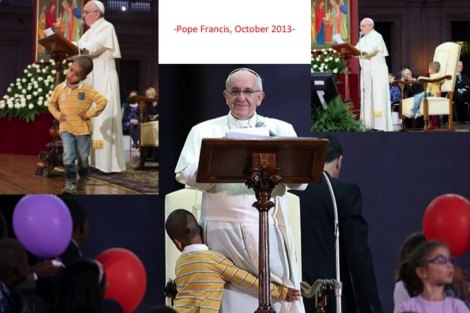

Returning to Pope Francis — he himself is cited as stating that such a position at such an age was 'crazy'. Perhaps it was but now we are gifted a Pope who allows a young child to share a stage, to sit on his chair whilst he continues to speak, to hug his legs and to generally be a child.

Returning to Pope Francis — he himself is cited as stating that such a position at such an age was 'crazy'. Perhaps it was but now we are gifted a Pope who allows a young child to share a stage, to sit on his chair whilst he continues to speak, to hug his legs and to generally be a child.

The voice of the child or adolescent can be heard in this text — notably the chapters dedicated to 'Handing on the Faith in Schools' (3), and 'Dealing with Child Sex Abuse' (5). It is sobering to be reminded by Frank that Colmar Brunton Social Research undertaken as part of the National Human Rights Consultation during the years 2008–2009 found that 51 per cent of people surveyed felt that children were in greater need of protection (7). And that is presumably without surveying any children!

When speaking with reference to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Frank stated: 'When dealing with child abuse, we all know that the real points of intersection are with state police forces and state child welfare departments.' Parents and those who work with children — teachers, doctors, therapists, carers — will be aware that these are fallible agencies.

Is it faith that gives us the resilience to remain engaged with a vulnerable child for periods of days, weeks or months when attempts to agitate the very agencies that are meant to protect children have failed? Is it conscience that assists us to avoid the perilous temptation to conceptualise these agencies as overtly 'good' or 'bad' thereby polarising our stance and restricting our options?

Catholic tradition, informed by Christian theology, demands social justice for the small, still voices. 'Suffer the little children to come unto Me', says Our Lord.

Frank has cited Cardinal Pell who criticised him publicly saying that 'part of the key to understanding Brennan is that he's really not well educated in the Catholic tradition — in Catholic theology' and that for the Jesuits, Jesus 'has been almost displaced by (their) enthusiasm for social justice'.

This is a book that grapples with topics as diverse as 'Espousing Marriage and Respecting the Dignity of Same Sex Couples' (13) through to 'Insisting on the Separation of Powers' (8). Having read these chapters, I believe that Frank would have us walk alongside the transgendered adolescent and not shy away from talking about the limitations of a legal system in which issues pertaining to the judiciary can directly increase the vulnerabilities of the parents of a murdered child.

It is here, at the edges, where pain is real, that this walking and talking, this theologically informed practical application that might be termed 'social justice', is seen as integral to Catholic theology and tradition.

Emme: Frank — next time you publish a collection of your work, and I know it will be a little while away, could you think about including 'children' or 'young people' as important terms in your index?

Family

This book has been dedicated to my grandparents 'Gerard and Patricia who made a home for conscience'. The book makes reference to the fact that Frank's vestment — pictured here in multiple family weddings — was lovingly made by my grandmother — a woman whose skill set not only included making a tapestry of the pulpit painting but was also a fine medical practitioner caring especially for the still small voices of children with mental and physical disabilities.

In chapter 12 'Respecting Autonomy and Protecting the Vulnerability of the Dying', Frank quoted my grandmother — whom I can see as clear as day — offering comment when Frank informed her of the speech to be given: 'Well there is not much to say about euthanasia is there? Just don't kill people and look after them while they are dying. What more can you say?'

In chapter 12 'Respecting Autonomy and Protecting the Vulnerability of the Dying', Frank quoted my grandmother — whom I can see as clear as day — offering comment when Frank informed her of the speech to be given: 'Well there is not much to say about euthanasia is there? Just don't kill people and look after them while they are dying. What more can you say?'

Well Grandma, I am not certain that I share your view. Just as Pope Francis did not know all the answers at age 36 years, neither do I. And I am sure time is not the sole missing ingredient here. I strongly suspect that Grandma would accept that this chapter articulates issues that cannot be ignored, even when the physical pain and/or emotional anguish of the terminally ill patient is so gut wrenchingly and rawly in front of you.

I continue on unsure that I am yet to align myself with the view that the church promotes on this issue, but I cling to Frank's final words as he concludes this text: 'without trust between those whose consciences differ, we will not scale the heights of the silence of the Godhead nor plumb the depths of the suffering of humanity; we will have failed to incarnate the mystery of God here among us.'

Of course most of you will have ascertained that I am also the eldest grandchild of Sir Gerard Brennan — he would not at all mind that I have listed my grandmother's achievements ahead of his own. Frank dedicated this book of reflection: 'to my father in gratitude for his amplification of the conscientious nudgings of so many and to my mother who has always called us back to that still, small voice.'

There are segments of this book that speak to the importance of the Mabo decision and as one of the few members of my immediate family who have not studied law, my comments on the impact of this judgement are far more pedestrian.

Without wanting to minimise the incredible impact that this decision has for Aboriginal people across this land, I myself was struck when I entered my youngest child's daycare centre — predominantly populated by white, middle class families — and observed a permanent sign placed centrally in the hallway, reminding all who walk past of the date, meaning and importance of Mabo Day.

And so I return to that small voice — the voice of the child walking down the child care hallway. Citing Judge Moynihan, within his lead judgment in the 1992 High Court Mabo decision, Sir Gerard Brennan puts light on the reality that:

'[Torres Strait Islander] Children were inculcated from a very early age with knowledge of their relationships in terms of social groupings and what was expected of them by a constant pattern of example, imitation and repetition with reinforcing behaviour. It was part of their behaviour — the way in which they lived.'

You see, even in a document that has now permeated through the tapestry of our national history, there exists this small voice. The voice of those who only benefit when agencies and institutions act in ways that genuinely protect young people, when the powerful acknowledge the vulnerability of the young, and when the remainder of us hold to the idea that our formalised systems leave room for our individual, informed conscience to step up and amplify that which is stifled or perhaps even muted.

In concluding tonight, I wish to finish the way I would wish to proceed — to enable a small voice to be heard expressing what matters:

Luke: Thank you Frank.

KATEENA [Melbourne launch]

It is an honour to speak at the launch of Frank's new book. In our family, Frank is a much-loved uncle, and now great-uncle. My nephew, Liam, recently attended interviews to gain admission to Catholic high schools in Brisbane. At one interview, the principal said to him:

'I can see your uncle is Frank Brennan, I am a big fan of his.'

Liam replied earnestly:

'Ooh yes but you do know he's a priest; not a person?'

He then added:

'I am in some of his books you know'.

I am not sure that Liam is mentioned in this book. But it is a book of which Liam would be proud. Having reached the age of reason, Liam often reflects on the normative principles that ought to guide his life. Frank's essays do not touch on the Morality of Train Timetabling, but Liam's book would.

It is especially an honour to speak at the launch of this book, given that it is dedicated to my grandparents, Gerard and Patricia. The dedication is that they 'made a home for conscience'. I think they not only made a home for conscience. They also taught by example the importance of informing that conscience — not just from one's own experiences, but from observations of the experiences of others.

It is especially an honour to speak at the launch of this book, given that it is dedicated to my grandparents, Gerard and Patricia. The dedication is that they 'made a home for conscience'. I think they not only made a home for conscience. They also taught by example the importance of informing that conscience — not just from one's own experiences, but from observations of the experiences of others.

Two days ago was the 23rd anniversary of the High Court's Mabo decision, which recognised native title. Gerard wrote the leading judgment in that decision in which the common law recognised the lived experiences, and the traditional laws, of Australia's native people.

During part of her working life, Patricia worked with disabled children. A few years ago, I was out at lunch with my grandparents when Patricia introduced herself to a disabled child who was lunching with her parents at a nearby table. Watching the interaction, my eyes were opened.

Perhaps from her work, Patricia had learned the truth that Stella Young, the much-loved disability advocate, said that she learned at age 17: 'That I was not wrong for the world I live in. The world I live in was not yet right for me.'

Patricia had learned enough about some children's experiences to know how to make the world of stuffy-restaurant-introductions-and-conversations right for the child she had only just met.

In his book, Frank relies from time to time on natural law reasoning. Both my grandparents inform the propositions they take to be 'self evident', or naturally true — not just from an attention to their own experiences — and the truths that appear 'self evident' in light of those experiences — but from an attention to the experiences of others. Both appear to me to define natural reason by reference to the experiences of others.

This is not to say that their conclusions remain ever-tentative. On the chapter concerning euthanasia, Frank tells of the occasion when he told Patricia that he was to speak on the topic of Euthanasia. Her response: 'Well there is not much to say about euthanasia is there? Just don't kill people and look after them while they are dying. What more can you say?'

My grandparents' approach to matters of conscience highlight the tension at the heart of natural law, and the Catholic Church's teachings on conscience. There are some propositions of which we can be 'absolutely certain'; there are other propositions of which others are 'absolutely certain' but which our independent consciences should question and ultimately reject.

So: how do we sift the truths from the non-truths? And what does the faithful Catholic do when it is the Pope who is 'absolutely certain' of a proposition that, to us, seems doubtful or, perhaps, egregiously and hurtfully wrong?

From my reading of Frank's book, and from conversations with him, I think Frank tells us to do two things when grappling with a doubtful proposition. First, reflect and reason on the reasons why that proposition may seem wrong and unacceptable for some people in some circumstances.

To undertake this task, I think Frank shows by example the importance of conversation; and the importance of ensuring that the truths we take to be self-evident are those propositions that fit with the wide range of experiences lived by different people, especially the most vulnerable.

The front cover of the book shows Frank standing alongside the relatives of Ian Ward, an Aboriginal elder who had died in custody because of 'the inhumane way in which he had been transported in suffering heat'. After the photo was taken, Frank sat in the back of the courtroom and listened to the evidence given to the coronial inquest into Mr Ward's death.

When forming our independent conscience, Frank's example suggests that there is a need for quiet, solitary reflection: after all, the voice is still and small. But there is also a need for dialogue, debate and reconsideration: because Elijah did not find the Lord in the wind, fire or earthquake that he encountered on his own. He found the Lord in a voice. Frank's essays suggest that the voice's message is discernible only after it is informed by the teachings and experiences of others.

In a chapter on same-sex marriage, Frank recounts the story of when Joe Hockey was asked this question: 'tell us and Senator Wong why you think you and Melissa make better parents than her and Sophie?'. Mr Hockey's response was this: 'I think in this life we've got to aspire to give our children what I believe to be the very best circumstances and that's to have a mother and a father'.

It is not clear that Mr Hockey reached his conclusion after having conversations with any children who were raised by same-sex parents; or after having conversations with any parents who raised a child with a partner of the same sex. Maya Newell is the child of two lesbian parents. She made the documentary Gayby Baby, which tells the stories of children raised by a same-sex couple. She tells her story this way:

'I have loved growing up with two mothers,' she says. 'In my opinion, children need love, security and support, and it doesn't matter if that is given by one parent, two parents or more. I hope that in watching this film, audiences will be inspired to interrogate 'what is family' and how and by whom is it defined.'

When forming our consciences on issues of same-sex parenting, Frank's approach identifies the need to pay close attention to the experiences of Maya Newell. Likewise, when forming our consciences on issues of same-sex marriage, I am not sure that it is the heterosexual's experience with marriage that is definitive. In November 2010, Frank wrote that:

'Many same sex couples tell us their relationship is identical with marriage. Until the majority of married couples are convinced this is so, politicians would be wise not to consider undoing the distinction between marriage and civil unions.'

But I think that by December 2014 Frank's views evolve. He then writes:

'Given that there is little support on either side [of politics in Australia] of the argument for civil unions, I accept that same sex marriage is the only way ultimately to extend equality and respect to same sex couples wanting state endorsement for their committed relationships, and that the state has an interest in supporting such relationships.'

Reading Julian Barnes' account of his grief for his wife, it is hard to see how the essence of marriage — their life together — was any different from the essence of a devoted same-sex union. Barnes writes:

'You put together two people who have not been put together before. Sometimes it is like that first attempt to harness a hydrogen balloon to a fire balloon: do you prefer crash and burn or burn and crash? But sometimes it works, and something new is made, and the world is changed. Then, at some point, sooner or later, for this reason or that, one of them is taken away ... [Then], everything you do, or might achieve thereafter, is thinner, weaker, matters less.'

To my eyes, it is hard to distinguish this account of marriage from the account of another English novelist, Ivy Compton-Burnett, whose union was with a woman. Barnes recounts Ivy's story of grief:

'Ivy ... missed Margaret Jourdain with 'palpable, angry vehemence'. To one friend she wrote, 'I wish you had met her, and so met more of me.' After being made a Dame of the British Empire, she wrote: 'The one I miss most, Margaret Jourdain, has now been dead 16 years, and I still have to tell her things. ... I am not fully a Dame, as she does not know about it.'

Frank's apparent change in views about same-sex marriage brings me to the second instruction that Frank offers on the most difficult issues of conscience. When trying to sift a truth from a non-truth, I think Frank suggests that we need to be brave enough to admit and to identify the mis-steps that we used to make in our reasoning.

In the first chapter, 'Celebrating a New Pope', he cites Pope Francis's struggles with a life initially lived with insufficient dialogue with others, and insufficient attention to the experiences of others:

'My authoritarian and quick manner of making decisions led me to have serious problems and to be accused of being ultraconservative. I lived a time of great interior crisis when I was in Cordoba. … It was my authoritarian way of making decisions that created problems. … Over time I learned many things.'

In response, Frank writes: 'What a Jesuit; what a pope; what a man!'

In the introduction, Frank states that 'as priest and lawyer, I have always regarded myself as an ambassador for conscience'. Occupying that role in the public sphere cannot be easy; especially when you consider the contentiousness of the issues that the ambassador for conscience must address; especially when you consider that any mis-steps in reasoning are made on the public record; and especially when you consider what the Church's teachings on sex, reproduction and homosexuality actually are. In this book, Frank offers up the fruits of his work as an ambassador for conscience.

Originally, Frank's great-nephew Liam told the principal of the Christian Brothers school: 'but you do know he's a priest; not a person?' Given that he was trying to gain access to the Christian Brothers school, it was probably not politic for Liam to skite about Frank, the way Frank skites about Pope Francis, 'What a Jesuit!' But on reflection, and after reading this collection of essays, I think Liam will ultimately skite: 'What a priest! And what a person!'