‘Someday soon … tennis fans are going to have to get their heads around the fact that Djokovic must now be mentioned when we discuss who is the greatest men’s player of all time.’

Gerald Marzorati, The New Yorker, Sep. 14, 2015

No tennis player in the modern era has garnered so much attention off and on the court. His genius is sublime, his steely mental resilience the stuff of legend. But even as Novak Djokovic savours his 24th grand slam at the US Open, putting him on par with Australia’s own Margaret Court as the most accomplished accumulator of such victories in tennis history, the jury remains testy, ever ready to qualify.

This says much about the expectation of a sports figure. They are, on some level, expected to be anodyne, their personalities cardboard crusting in dullness and subordinate to their performance. Within these prisons of flesh and athleticism, they are meant to perform with supreme professionalism and keep their views to themselves. If any views are to be expressed, they must be sanitised to fit either the authoritarian voice of sporting administration, or the trendy voice of the enraged.

From the perspective of principle and behaviour, Djokovic has baffled the critics, unnerved the establishment, and provided endless column space for tennis writers. His behaviour during the Covid pandemic was erratic, haughtily defiant, and, worse, indifferent to consequences. His own conviction about pure living, the body as a temple that should be free of heretical impurities, led to a confidence almost verging on arrogance. Even after a positive covid test in Belgrade, he still ventured out to a ceremony. In June 2020, he helped organise, with dismal results, the Adria Tour tennis tournament as the rest of the sporting circuit went into hibernation. (It was abandoned after being struck by Covid infections, with Djokovic publicly apologising ‘for each individual case of infection’.)

Despite his personal inclinations, the treatment offered by the Australian government in 2021 was shabby at best, atrocious at worst. Both he and his entourage had been led to believe that entering Australia at that time to compete in the Australian Open would still comply with pandemic regulations. Two bodies, Tennis Australia and a State expert panel, agreed that he could still enter, notwithstanding his unvaccinated status. Having been infected during the designated interval prior to entering Australia, he assumed that all requirements had been met. Not so, came the hard reality facing Djokovic at Melbourne International Airport.

Having won the first case (‘The point I am agitated about is,’ declared Judge Anthony Kelly, ‘what more could this man have done?’), temporarily enabling him to remain in the country, Djokovic the quintessentially talented tennis player vanished from view. His fate became a political tangle of ferocious, often vitriolic debate. As he lobbed balls in training and awaited the decision of Immigration Minister Alex Hawke, who had the final say on whether his visa would be cancelled, pro- and anti-vaccination groups battled. Libertarians expressed admiration for the man and loathing for heavy-handed Australian regulations. A number of Serbian nationals shook their heads in dismay, convinced their hero was being targeted for his nationality.

All these calls were eclipsed by a near vengeful desire to deport Djokovic, who became the convenient, politicised scapegoat for Australia’s strict vaccination policies. Leave, went the general sentiment. You did not take the jab. You dared appeal your decision through legal channels and question Australian authorities. You posed a threat to the public health system by encouraging the anti-vaccination dogma. The Full Court of the Federal Court, in more legally larded language, tended to agree, refusing to accept the fact that Djokovic did not proselytise his stance on vaccination, and could hardly constitute a threat to a population with such high vaccination rates.

'He yearns, or so we are told by his critics, to be loved. Often these are the same critics who would leave him unloved, even actively disliked. This ridiculous calculus of rejection and yearning works full circle, shamefully exiling talent and tennis from the discussion.'

This may explain why much commentary on the man trivialises his monumental achievements. Grand slam victories are passed over in favour of personality complexes and infantile yearnings. The man displaces the talent; behaviour takes the place of appreciating on court glory.

More fundamentally, the Serb national conveniently slots into an imposed villainous role, one played opposite his two other canonised rivals in the same era, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. The stratospheric rise of Carlos Alcaraz has again enabled fans to assume customary positions: the youthful challenger intent on overthrowing the dark overlord. ‘Djokovic will always be the villain of the movie,’ former professional tennis player Nicolas Pereira opines. ‘You have to enjoy him with the good, the bad and the ugly.’

Precisely because he speaks his mind, all bets are off. The personal becomes grounds for critique. He yearns, or so we are told by his critics, to be loved. Often these are the same critics who would leave him unloved, even actively disliked. This ridiculous calculus of rejection and yearning works full circle, shamefully exiling talent and tennis from the discussion.

The other side of such views is Djokovic’s outsized, stadium-like determination to stick to the path. From his obstinate views about vaccination, to the Kosovo question or players’ rights, he will offer an opinion if it is sought. But whatever such views entail, the need to maintain a degree of disinterestedness in appreciating the remarkable achievements of this player is only fair. Time, even, to appreciate greatness for what it is.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University.

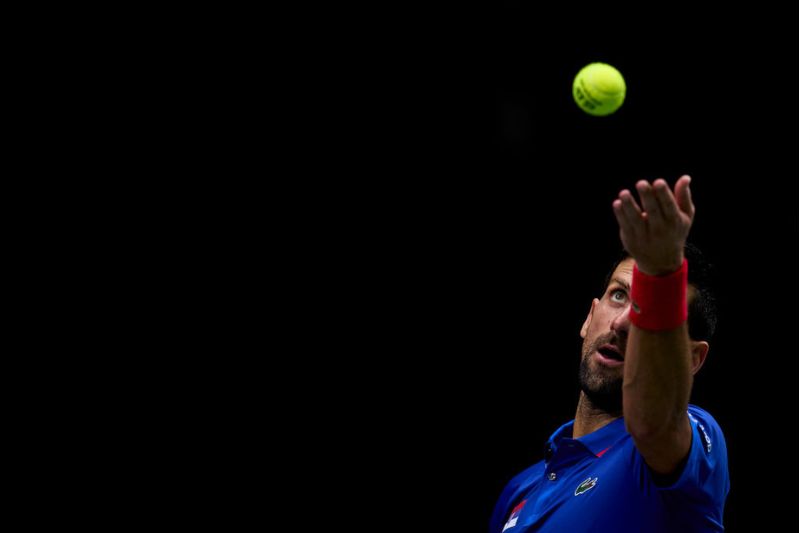

Main image: Novak Djokovic serves a ball on his game against Alejandro Davidovich Fokina of Spain during the match between Spain and Serbia during the match between Spain and Serbia as part of the 2023 Davis Cup Finals Group Stage at Pabellon Fuente De San Luis on September 15, 2023 in Valencia, Spain. (Aitor Alcalde/Getty Images for ITF)