When I was about 16 years old, my father took myself and my siblings to an exhibition on the Stolen Generations entitled Between Two Worlds. Though I had grown up knowing about the Stolen Generations, it was the first time I truly connected that my grandmother Emily Liddle (nee Perkins) was a part of it.

I always knew she had been taken; that was well understood. What I didn't understand until that exhibition was what she had been through and what being a member of the Stolen Generations meant. Though my grandmother passed away several years ago now, her audio account procured for this exhibition has been preserved online, so I can hear her story again at the click of a button.

I always knew she had been taken; that was well understood. What I didn't understand until that exhibition was what she had been through and what being a member of the Stolen Generations meant. Though my grandmother passed away several years ago now, her audio account procured for this exhibition has been preserved online, so I can hear her story again at the click of a button.

Back then, the most shocking thing to me about her account was hearing that her and the other girls at Jay Creek Mission slept on hard concrete floors with just a couple of blankets for comfort.

Later on, as I became more active in workers' rights and heard about the continued campaign to retrieve Stolen Wages, my focus shifted to her 'education' while in the mission. As she describes, her and the other girls were trained in domestic skills then were eventually given to wealthy white families to serve as mostly unpaid servants.

This was not uncommon. All over the country, Aboriginal people were forced into labour. In most cases the majority of their wages were held in government trusts, never to be seen again. According to what I have heard from family, my grandmother was treated well by the family she worked for, yet this does not make what happened to her and so many other Aboriginal workers right.

While other people in this country have inherited wealth from their forebears, Aboriginal people are still fighting to receive payments from decades ago. This goes part of the way to explaining why so many remain in poverty.

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the Wave Hill Walk Off, along with the 70th anniversary of the Pilbara Strike. Last week also marked the 66th anniversary of the Darwin Strikes. In all three instances, Aboriginal workers were paid a pittance, if at all, and many were abused. Aboriginal women were often sexually exploited by white masters and workers with resultant children taken off them by authorities.

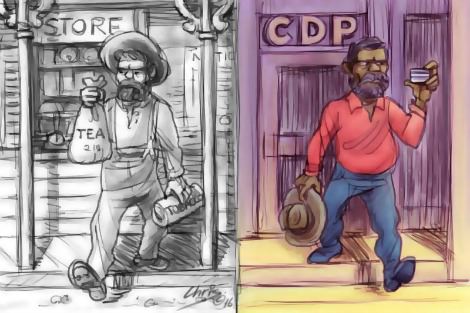

In the case of Pilbara, tea and tobacco seemed to be the going rate for labour. Meanwhile, the Darwin Strikes are notable in these press clippings because while there was support for the Aboriginal workers from the NAWU, this union was not able to bail out arrested strikers because these workers were under the guardianship of the Territory and their employers.

"It would be nice to think that free Aboriginal labour is firmly rooted in the shame of the past and as a nation, we have moved forward ... but the exploitation of the most vulnerable in our community continues."

Wave Hill, of course, is more well-known among the general Australian public because of the iconic photo of Gough Whitlam pouring sand into the hand of Vincent Lingiari, and the Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly song 'From Little Things Big Things Grow'.

In all three cases there was collaboration between unions and Aboriginal workers. Among other actions, the Seamen's Union of Australia put a black ban on shipping wool from the Pilbara region during that strike. During Wave Hill, union members paid a levy to ensure the Gurindji had supplies and could raise awareness of their actions. Along with other gains from these actions, the right to pay Aboriginal people less and hold their wages in trusts was chipped away at until eventually, as late as 1986, the Queensland Government agreed to equal wages for Aboriginal people working on missions.

It would be nice to think that free Aboriginal labour is firmly rooted in the shame of the past and as a nation, we have moved forward. Yet in 2015, the Federal Government decided to roll out the 'Community Development Program' (CDP) in remote areas of the country. The CDP is a remote Work for the Dole program and has been widely condemned; not just by the Australian Council of Trade Unions but also by recent Jobs Australia report which shows how harmful it is. People engaged in the Community Development Program are required to work 25 hours per week year round for only their Centrelink payments and if they fail to comply, they can be cut off. Reports show a community-wide decline in purchase and consumption of fresh food as participants are cut off from their payments leaving other impoverished family members more financially-stretched.

Not only do government placements form part of the work these community members can be engaged in, but private enterprises are also eligible to become CDP providers. This essentially means that businesses have the ability to profiteer off free labour.

The government has repeatedly claimed how the CDP is not discriminatory program using the justification that not only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are engaged in it. However, in the regions where CDP operates, about 83 per cent of the unemployed people are Indigenous. It is therefore targeted, and the fact that it resides in the Indigenous Affairs portfolio proves the point.

In addition, it is telling that a number of these placements revolve around work which anywhere else in the country would be covered under basic community services such as council services and would therefore attract a proper wage. What incentive is there for governments to properly fund remote councils to employ Aboriginal workers if they can simply engage these people for free? What incentive is there for private enterprises to hire Indigenous workers if they can continue to profiteer off an endless pool of Indigenous labour?

The years may have ticked over, but the government's attitude to the value of Indigenous workers has not. Indigenous workers of previous generations struggled and undertook strike actions so that their descendants would not be exploited and abused in the same way that they had been. While we may have many more Aboriginal people achieving and attracting higher waged work than we did in the years gone by, the exploitation of the most vulnerable in our community continues. And though the union movement is determined to take a stand and ensure that Indigenous workers receive proper working payments and entitlements, a good portion of the country continues to turn a blind eye. It is through this social complicity that we ensure the wealth gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is doomed to remain a gaping chasm for a long time to come.

Celeste Liddle is an Arrernte woman living in Melbourne, the National Indigenous Organiser of the NTEU, and a freelance opinion writer and social commentator. She blogs at Rantings of an Aboriginal Feminist.

Celeste Liddle is an Arrernte woman living in Melbourne, the National Indigenous Organiser of the NTEU, and a freelance opinion writer and social commentator. She blogs at Rantings of an Aboriginal Feminist.

This is the latest article in our ongoing series on work.