In 2015, a year before the launch of TikTok, Twitter launched an app called ‘Periscope’. The app allowed users to watch broadcasts of other people’s lives. Some people would walk with their dog in a mountainous forest; others were experts in in anything from musicology to mediaeval literature and would talk extensively on their subject, taking questions. When protests or fires broke out, Periscopers would be there, hashtagging away while millions tuned in.

But, as Coburn Palmer wrote in a 2015 article in Inquistr, the possibilities offered by these kinds of social media platforms generally go unfulfilled: ‘Live-streaming apps have the potential to increase citizen journalism and revolutionise the way traditional news outlets operate, but so far have been mainly used to showcase the contents of users’ refrigerators.’

Seven years later, TikTok dominates the social media scene. It’s the fastest growing platform, with one billion active monthly users. With the introduction of each new platform, the way we engage with social media changes. Facebook brought us the word ‘slacktivism’: the practice of supporting a social or political cause with very little effort involved. Instagram spread hashtags like COVID at a kid’s party. And now we have TikTok, a never-ending stream of frenetic videos which harness the power of hashtags to create ‘trends’. There are dance trends, filters, sound bites, green screens, and make-up artists creating surrealist creatures out of their faces.

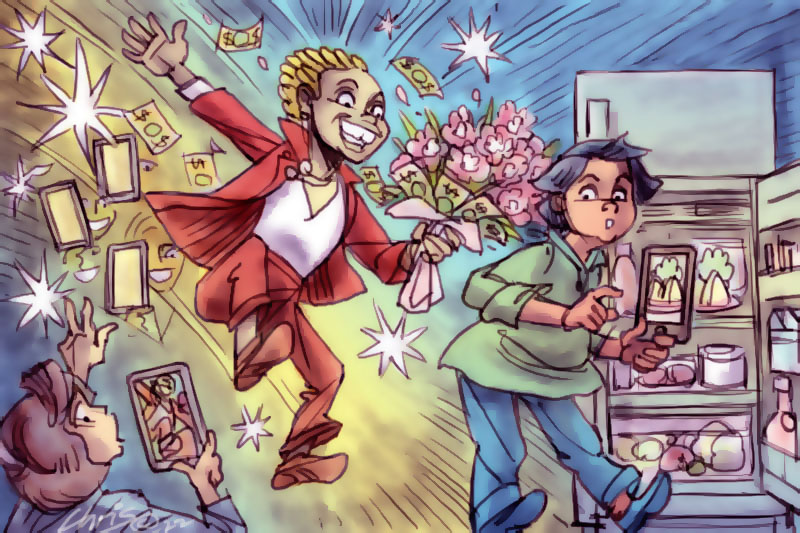

And then there’s #randomactsofkindness. It’s a nice idea. Harrison Pawluk, a 22-year-old Australian TikTok celebrity, films himself giving flowers to a woman enjoying her coffee alone, and the video is viewed over 65 million times. He uses hashtags #foryou and #wholesome. Turns out, she felt #dehumanised by the whole thing. ‘He interrupted my quiet time, filmed and uploaded a video without my consent, turning it into something it wasn’t, and I feel like he is making quite a lot of money through it,’ she said to Virginia Trioli on ABC Radio Melbourne.

'If an act of kindness happens and no one is there to film it, did it really happen?'

We all know the Internet can be a seething cesspool of vitriol, so the presence of heart-warming videos of people slipping $20 into someone’s coat pocket or randomly complimenting a stranger, even the ubiquitous handing out of flowers, is largely welcome. But is this actually kindness? If an act of kindness happens and no one is there to film it, did it really happen?

Ironically, in the age of COVID, going viral is the prize. TikTokers play to an astounding number of people globally, all eager for views, likes and comments. Brands line up, throwing cash at them to be associated, achieving a greater reach than both brand and creator alike could have previously imagined was possible. According to Forbes, the top earning TikToker Charli D’Amelio earned $17.5 million in 2021 in brand deals and endorsements.

So, back to Harrison Pawluk. Is it possible that a TikTok ‘celebrity’ with 3.2 million followers, intent on building a personal brand, is doing #randomactsofkindness for selfless reasons? Harrison himself claimed in an interview on The Project, ‘If I can inspire even one per cent of the people that watch my content to go out there and do something good, I have done something that I believe is good for the world.’ A recent video shows him giving a stranger a makeover. The finishing touch? A necklace from the shop which sponsored the video (the same necklace he appears to be wearing on The Project).

Why should kindness be selfless anyway? Perhaps he’s killing two birds with one stone: inspiring others to be kind while reeling in the sponsors. But it just feels icky. Maree, the lady he gave flowers to, said, ‘it’s not really about me anymore’. It’s a bit like when your sister gave you that CD for Christmas which you knew she secretly wanted and will probably listen to more than you will. A tokenistic gesture that reaps personal rewards.

Recently, I was at a drive-thru coffee, experiencing one of those hellish car trips with my kids, my nerves thoroughly frayed. I pulled up at the window to pay and the girl announced it was free, courtesy of the car before me who’d donated their free coffee from a loyalty card. This person didn’t know me. I could have been driving a BMW and afforded to buy the next thirty people coffee myself. But the small act of kindness landed. No one witnessed it except the people working at the shop. The driver drove off, no one around to pat them on the back for their good deed — certainly not an audience of millions with corporations knocking on their door.

While acts of kindness performed for a TikTok audience feel tacky, there is something inherently noble in the countless kindnesses that go unwitnessed. The people who serve their community in a million quiet ways: donating to food banks, volunteering, knitting hats for babies they’ll never meet, giving blood. Social media has made a giant stage of the world, and the performance of acts of ‘kindness’ now seems to be mostly inspired by a desire to serve one’s own celebrity rather than the common good.

.png)

Perhaps our motivations can never be pure; but why does purity of motive matter? Because an act of kindness should be an exercise in turning our focus outward, towards others, unfettered by any thought of what we might receive in return. In order to achieve its goal, kindness must surely be grounded in sincerity rather than being performative or acquisitive in nature — its goal being to bring happiness to others rather than to benefit ourselves, to make others feel valued and respected, and in doing so to effect positive change in our communities.

Nevertheless, I do miss the good old days when livestreaming was a peek in someone else’s fridge.

Cherie Gilmour is a writer from Torquay whose work has appeared in The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald and Mindfood magazine.

Main image: Illustration by Chris Johnston