I am delighted to participate in this conference 'Human Rights Matters!' marking Anti-Poverty Week 2012. I applaud Catholic Social Services Victoria, the St Vincent de Paul Society, Social Policy Connections, ACOSS, the Public Interest Law Clearing House, UnitingCare Community Options, and Women's Housing Ltd for this initiative. I note that some of the sponsoring bodies have been at the forefront of novel developments in human rights protection in Canberra. Countering the joint approach of the major political parties, you have been able to agitate the human rights ramifications of radical cuts to welfare payments made to 140,000 single parents of young dependent children who have now been placed on the Newstart Allowance which has not seen any real increase since 1994. But more of that anon. I have been asked to share with you some of the lessons from the National Human Rights Consultation which I was privileged to chair in 2009.

Speaking to the Anglo-Australasian Lawyers Society in London in July this year, Chief Justice Robert French introduced his paper with this observation about Australian exceptionalism on human rights protections:

Australia is exceptional among Western democracies in not having a Bill of Rights in its Constitution, nor a national statutory Charter of Rights. A recent academic article in the European Human Rights Law Review used as a subheading the well-known Australian saying, 'she'll be right mate', intending to convey what the authors described as 'Australia's lukewarm attitude towards human-rights specific legislation.' There have been frequent criticisms of Australia's perceived exceptionalism in this respect and laments about its relegation to a backwater, while the great broad river of international human rights jurisprudence sweeps by.

He pointed out that Australian judges had many human rights protections in their armoury including the common law, strict techniques of statutory interpretation, the principle of legality, implied rights in the Constitution, and a robust expanding reading of the exclusive province of judges to exercise uncontaminated judicial power under Chapter III of the Constitution. Fourteen years since the UK enacted their Human Rights Act, Chief Justice French seems fairly sanguine that the Australian judiciary can arrive at the same conclusions as their fellow judges in human rights jurisdictions, without the need for the Commonwealth Parliament to enact a Human Rights Act. I don't know that his successor will be so sanguine once the Australian judicial isolation becomes inter-generational. If Australian judges are going to continue reaching the same conclusions as judges in human rights jurisdictions by using substitute techniques, you would wonder why the entrenched objection to human rights legislation. If over time, Australian judges are going to reach significantly different, human rights deficient decisions, there will be a need for some further human rights legislation.

At the conclusion of his address, Chief Justice French said:

A prominent element of the arguments advanced against the introduction of constitutional and statutory charters in Australia is that they would shift power on important matters of social policy from elected politicians to unelected judges. There is no doubt that human rights and freedoms guaranteed in constitutions and statutes around the world are broadly expressed. The definition of their limits in particular cases by reference to public interest considerations necessarily requires normative judgments which may be seen to have a legislative character.

Though our politicians remain mistrustful of judges possessed of a Human Rights Act, they have been prepared to enhance human rights scrutiny of all new Commonwealth legislation. At the pre-legislative stages there is now provision under the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth) for statements of compatibility and review by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights.

Australia takes seriously its ratification of the key UN human rights instruments. Seven of those instruments require the Australian government to provide regular reports to UN committees about compliance and there is an increasing capacity for disaffected persons having exhausted all domestic remedies to bring their own complaints to the UN. In this case, it makes sense for our legislators to be apprised of these obligations before they legislate. Thus the dual approach — the provision by the executive of statements of compatibility and the Parliament's institution of a Committee on Human Rights.

I was privileged to chair a committee of very competent individuals who had diverse views about how best to protect human rights in Australia. The other committee members were Mary Kostakidis, a well known national television news presenter and board member of leading humanitarian and cultural organizations, Mick Palmer retired Northern Territory Police Commissioner and Australian Federal Police Commissioner who had conducted the inquiries for the Howard government into unauthorized immigration detention, and Tammy Williams an indigenous lawyer whose family has been involved in litigation for the stolen generations and for stolen wages. We were also assisted by Philip Flood retired head of the Department of Foreign Affairs and retired ambassador who had done the review of the national intelligence services for the Howard government. The Murdoch press was fond of portraying us as a group of likeminded lefties. The diversity of our views ensured the transparency and integrity of our processes, especially given that we did not reach agreement on the recommendations about a Human Rights Act until five minutes to midnight.

We utilised the new technology as well as conducting community consultations and receiving tens of thousands of submissions. I ran a Facebook page. We hosted a blog and commissioned academics on opposite sides of the argument to steer the blog debate on a human rights act. We held three days of hearings in Parliament House which were broadcast and oft repeated on A-PAC, the new Australian Public Affairs Channel — a C-Span type television station.

During the consultation, groups like GetUp! and Amnesty International ran strong campaigns in favour of a Human Rights Act. However they largely abandoned the field once our report was tabled. The opponents of a Human Rights Act then went into action, including the Australian Christian Lobby and the influential leaders of the Anglican and Catholic Churches in Sydney — Archbishop Philip Jensen and Cardinal George Pell. The chief proponents of a Human Rights Act then seemed to be lawyers — easy targets, being identified as self-interested in generating further litigation.

In providing an overview of the Australian National Human Rights Consultation, I will provide a thumbnail sketch of our findings from the community consultations on the three questions posed by the government:

- Which human rights (including corresponding responsibilities) should be protected and promoted?

- Are these human rights currently sufficiently protected and promoted?

- How could Australia better protect and promote human rights?

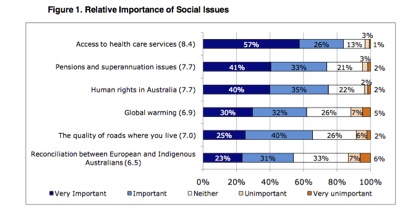

I will address the recommendation of a Human Rights Act and say a word about some of the misperceptions in the critique offered to our report. We engaged a social research firm Colmar Brunton to run focus groups and then to administer a very detailed random telephone poll of 1200 persons. This poll highlighted the issues of greatest concern to the Australian community:

Which human rights (including corresponding responsibilities) should be protected and promoted?

At community roundtables participants were asked what prompted them to attend. Some civic-minded individuals simply wanted the opportunity to attend a genuine exercise in participative democracy; they wanted information just as much as they wanted to share their views. Many participants were people with grievances about government service delivery or particular government policies. Some had suffered at the hands of a government department themselves; most knew someone who had been adversely affected—a homeless person, an aged relative in care, a close family member with mental illness, or a neighbour with disabilities. Others were responding to invitations to involve themselves in campaigns that had developed as a result of the Consultation. Against the backdrop of these campaigns, the Committee heard from many people who claimed no legal or political expertise in relation to the desirability or otherwise of any particular law; they simply wanted to know that Australia would continue to play its role as a valued contributor to the international community while pragmatically dealing with problems at home.

Outside the capital cities and large urban centres the community roundtables tended to focus on local concerns, and there was limited use of 'human rights' language. People were more comfortable talking about the fair go, wanting to know what constitutes fair service delivery for small populations in far-flung places. At Mintabie in outback South Australia, a quarter of the town's population turned out, upset by the recent closure of their health clinic. At Santa Teresa in the red centre, Aboriginal residents asked me how I would feel if the government required that I place a notice banning pornography on the front door of my house. They thought that was the equivalent of the government erecting the 'Prescribed Area' sign at the entrance to their community. In Charleville, western Queensland, the local doctor described the financial hardship endured by citizens who need to travel 600km by bus to Toowoomba for routine specialist care.

The Committee learnt that economic, social and cultural rights are important to the Australian community, and the way they are protected and promoted has a big impact on the lives of many. The most basic economic and social rights—the rights to the highest attainable standard of health, to housing and to education—matter most to Australians, and they matter most because they are the rights at greatest risk, especially for vulnerable groups in the community.

The community roundtables bore out the finding of Colmar Brunton Social Research's 15 focus groups that the community regards the following rights as unconditional and not to be limited:

- the right to basic amenities — water, food, clothing and shelter

- the right to essential health care

- the right of equitable access to justice

- the right to freedom of speech

- the right to freedom of religious expression

- the right to freedom from discrimination

- the right to personal safety

- the right to education.

Many of the more detailed submissions presented to the Committee argued that all the rights detailed in the primary international instruments Australia has ratified without reservation should be protected and promoted. Most often mentioned were the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966, which, along with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, constitute the 'International Bill of Rights'.

Some submissions also included the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women 1979, the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment 1984, the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006.

Having ratified these seven important human rights treaties, Australia has voluntarily undertaken to protect and promote the rights listed in them. This was a tension for us in answering Question 1. Many roundtable participants and submission makers spoke from their own experience highlighting those rights most under threat for them or for those in their circle. Others provided us with a more theoretical approach arguing that all Australia's international human rights obligations should be complied with.

True to what we heard from the grassroots, we singled out three key economic and social rights for immediate enhanced attention by the Australian Human Rights Commission — the rights to health, education, and housing. We think that government departments should be attentive to the progressive realization of these rights, within the constraints of what is economically deliverable. However, in light of advice received from the Solicitor-General, we did not think the courts could have a role to play in the progressive realization of these rights.

We recommended that the Federal Government operate on the assumption that, unless it has entered a formal reservation in relation to a particular right, any right listed in the seven international human rights treaties should be protected and promoted.

Are our human rights currently sufficiently protected and promoted?

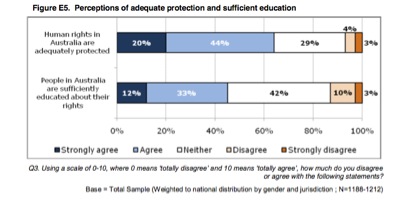

Colmar Brunton Social Research found 'only 10 per cent of people reported that they had ever had their rights infringed in any way, with another 10 per cent who reported that someone close to them had had their rights infringed'3. 10 per cent is a good figure, but only the most naively patriotic would invoke it as a plea for the complacent status quo. The consultants reported that the bulk of participants in focus groups had very limited knowledge of human rights. Sixty-four per cent of survey respondents agreed that human rights in Australia are adequately protected; only 7 per cent disagreed; the remaining 29 per cent were uncommitted.

The Secretariat was able to assess 8671 submissions that expressed a view on the adequacy or inadequacy of the present system: of these, 2551 thought human rights were adequately protected, whereas 6120 (70 per cent) thought they were not.

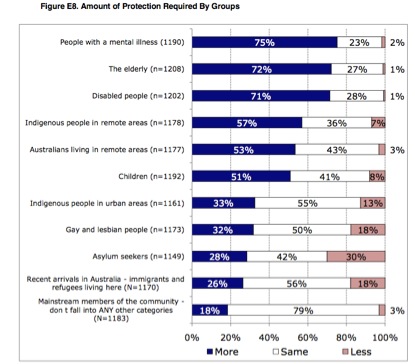

There is enormous diversity in the community when it comes to understanding of and perspectives on rights protection. Though two thirds of those who participated in the random survey thought human rights were adequately protected in Australia, over 70 per cent identified three groups in the community whose rights were in need of greater protection. This was the question put to respondents: 'I'm going to read out some groups now. For each, do you feel their human rights need to be given more, less or the same amount of protection as they are currently getting in Australia?' This was the response:

The majority of those surveyed also saw a need for better protection of the human rights of those living in remote rural areas. The near division of the survey groups when it comes to the treatment of asylum seekers highlights why the issue recurs at Australian elections.

How could Australia better protect and promote human rights?

The Committee commissioned The Allen Consulting Group to conduct cost—benefit analyses of a selection of options proposed during the Consultation for the better protection and promotion of human rights in Australia. The consultants developed a set of criteria against which the potential effects of various options were assessed; the report on the outcome of this assessment is presented as an Appendix to the report.7 Each option was evaluated against three criteria—benefits to stakeholders, implementation costs and timeliness, and risks. The options evaluated were a Human Rights Act, human rights education, a parliamentary scrutiny committee for human rights, an augmented role for the Australian Human Rights Commission, review and consolidation of anti-discrimination laws, a new National Action Plan for human rights, and maintaining current arrangements (that is, 'doing nothing').

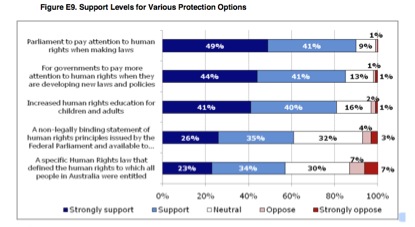

We put forward three tranches of measures to be considered for further protecting and enhancing human rights. I will deal with them in ascending order of controversy and in descending order of broad community endorsement.

Education and culture

At many community roundtables participants said they didn't know what their rights were and didn't even know where to find them. When reference was made to the affirmation made by new citizens pledging loyalty to Australia and its people, 'whose rights and liberties I respect', many participants confessed they would be unable to tell the inquiring new citizen what those rights and liberties were and would not even be able to tell them where to look to find out. In the report, we noted the observation of historian John Hirst 'that human rights are not enough, that if rights are to be protected there must be a community in which people care about each other's rights'. It is necessary to educate the culturally diverse Australian community about the rights all Australians are entitled to enjoy. Eighty-one per cent of people surveyed by Colmar Brunton Social Research said they would support increased human rights education for children and adults as a way of better protecting human rights in Australia.

At community roundtables there were consistent calls for better education. Of the 3914 submissions that considered specific reform options (other than or in addition to a Human Rights Act), 1197 dealt with the need for human rights education and the creation of a better human rights culture. This was the most frequent reform option raised in those submissions. While 45 per cent of respondents in the opinion survey agreed that 'people in Australia are sufficiently educated about their rights', Colmar Brunton concluded:

There is strong support for more education and the better promotion of human rights in Australia. It was apparent that few people have any specific understanding of what rights they do have, underlining a real need as well as a perceived need for further education.

This confirmed the Committee's experience of the community roundtables.

The Committee's recommendation that a readily comprehensible list of Australian rights and responsibilities be published and translated into various community languages follows from Colmar Brunton's finding that there was 'generally more support for a document outlining rights than for a formal piece of legislation per se'. There was wide support for this idea in the focus groups, and 72 per cent of those surveyed thought it was important to have access to a document defining their rights. Even more significantly, Colmar Brunton found:

In the devolved consultation phase with vulnerable and marginalised groups there was a very consistent desire to have rights explicitly defined so that they and others would be very clearly aware of what rights they were entitled to receive.

Sixty-one per cent of people surveyed supported 'a non-legally binding statement of human rights principles issued by the Federal Parliament and available to all people and organisations in Australia'. We recommended a readily comprehensible list of Australian rights and responsibilities.

Paul Kelly from The Australian thought our contempt for the Australian community breathtaking in our call for education of children 'so they understand the need to respect 'the dignity, culture and traditions of other people'.' I make no apology for this call. It is fanciful for commentators like Kelly to suggest that our 'report, in effect, seeks the obliteration of the Howard cultural legacy'. I know of no member of my committee who would claim knowledge of such a legacy, let alone a commitment to obliterate it. Such a task was well beyond our terms of reference. It is a figment of Kelly's patriotic imagination.

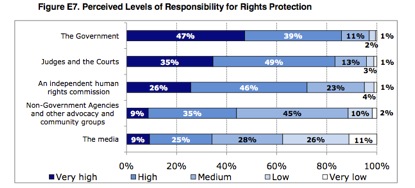

The Murdoch press made a strong claim that existing protections for human rights were adequate and that the occasional shortfall could be rectified by the investigative journalism of credible broadsheets such as their masthead The Australian. The public did not share this view:

Human rights compliance in the bureaucracy and in the preparation of legislation

The second tranche of proposals for enhancing human rights protection included recommendations for ensuring that Commonwealth public authorities could be more attentive to human rights when delivering services and for guaranteeing compliance of Commonwealth laws with Australia's voluntarily assumed human rights obligations. We recommended that the Human Rights Commission have much the same role in hearing complaints of human rights violations by Commonwealth agencies as it presently has in relation to complaints of unlawful discrimination.

Taking the lead from Senator George Brandis in his submission for the Federal Opposition, we recommended an audit of all past Commonwealth laws so that government might consider introducing amendments to Parliament to ensure human rights compliance. We also recommended that all future Commonwealth bills introduced to Parliament by the Executive be accompanied by a statement of human rights compatibility and that there be a parliamentary committee which routinely reviews bills for such compliance. These measures are fully respectful of parliamentary sovereignty. We recommended measures more thorough than the weak model of the Legislation Review Committee in New South Wales where parliament is able to receive the parliamentary committee report on human rights violations long after the legislation has been passed. We saw no point in window dressing procedures which close the gate only once the horse has bolted.

A Human Rights Act?

The third tranche of recommendations relates to a Human Rights Act.

Many Australians would like to see our national government and parliament take more notice of human rights as they draft laws and make policies. Ultimately, it is for our elected politicians to decide whether they will voluntarily restrict their powers or impose criteria for law making so as to guarantee fairness for all Australians, including those with the least power and the greatest need.

Our elected leaders could adopt many of the recommendations in our report without deciding to grant judges any additional power to scrutinise the actions of public servants or to interpret laws in a manner consistent with human rights.

The majority of those attending community roundtables favoured a Human Rights Act, and 87.4 per cent of those who presented submissions to the Committee and expressed a view on the question supported such an Act—29 153 out of 33 356. In the national telephone survey of 1200 people, 57 per cent expressed support for a Human Rights Act, 30 per cent were neutral, and only 14 per cent were opposed.

Our elected politicians could decide to take the extra step, engaging the courts as a guarantee that our politicians and the public service will be kept accountable in respecting, protecting and promoting the human rights of all Australians.

If they do choose to take that extra step, we have set out the way we think this can best be done—faithful to what we heard, respectful of the sovereignty of parliament, and true to the Australian ideals of dignity and a fair go for all. Our suggestions are confined to the Federal Government and the Federal Parliament. The states and territories will continue to make their own decisions about these matters. But we hope they will follow any good new leads given by the Federal Government and the Federal Parliament.

Part Four of our report deals with the issue of a Human Rights Act. It contains five chapters. First, it sets out previous attempts to legislate for a Human Rights Act in Australia and analyses why those attempts have failed. Second, it gives an overview of the statutory models in New Zealand, the UK, Victoria and the ACT. Third, it gives a dispassionate statement of the case for a Human Rights Act. Fourth, it gives an equally dispassionate statement of the case against a Human Rights Act. Fifth, it sets out the range of 'bells and whistles' that could be included in any Human Rights Act. This part of the report can stand alone as a useful resource for any citizen or Member of Parliament undecided about the usefulness or desirability of a Human Rights Act. The intended reader is the person who is agnostic about this question, not altogether convinced of the social worth of lawyers, wanting bang for the buck with social inclusion and protection of the vulnerable in society. I suspect few of the commentariat at Murdoch have read this part of the report.

Part Five of the report then contains the recommendations we made as a committee. We recommended a Human Rights Act. Despite sensational headlines in The Australian, I do not see any enormous problems with the model we have proposed. It would have no application to the States or the Territories. It would add two significant reforms to those in the first two tranches. Parliament would grant to judges the power to interpret Commonwealth laws consistent with human rights provided that interpretation was always consistent with the purpose of the legislation being interpreted. This power would be more restrictive than the power granted to judges in the United Kingdom. In the UK, Parliament has been happy to give judges an even stronger power of interpretation because a failed litigant there can always seek relief in Strasbourg before the European Court of Human Rights. Understandably, the English would prefer to have their own judges reach ultimate decisions on these matters, rather than leaving them to European judges. We have no such regional arrangement in Australia. Suva ain't Strasbourg!

Second, a person claiming that a Commonwealth agency had breached their human rights would be able to bring an action in court. For example, a citizen disaffected with Centrelink might claim that their right to privacy has been infringed by Centrelink. The court would be required to interpret the relevant Centrelink legislation in accordance with the Human Rights Act. If the court could so interpret the law, it might find that Centrelink was acting beyond power, infringing the right to privacy. Alternatively, the court would find that Centrelink was acting lawfully but that the interference with the right to privacy was not justified in a free and democratic society. It would then be a matter for the parliamentary committee on human rights to decide whether to review the law and recommend some amendment. Ultimately, it would be a decision for the responsible minister and the government as to whether the law should be amended. The sovereignty of parliament would be assured.

Consistent with international human rights law, we acknowledged that economic and social rights such as the rights to health, education and housing are to be progressively realized. Nothing in our recommendations would allow a citizen or non-citizen to go to court claiming a right to health, education or housing. The progressive realization of these rights would be a matter for the Government and the Human Rights Commission in dialogue. We recommended that some civil and political rights be non-derogable and absolute. This means that these rights cannot be suspended or limited, even in times of emergency. These rights include the right to life, precluding the death penalty; protection from slavery, torture, cruel and degrading treatment.

Some will argue that there is no prospect of these rights being infringed in Australia, so why bother to legislate for them? The facts that any infringement of these rights would be indefensible and that most Australians hold such rights as sacrosanct create a strong case, in the opinion of the Committee, for these rights being guaranteed by Commonwealth law.

If in future a Federal Parliament were to legislate to interfere with these rights — as it could in theory, considering that not even these rights are included in the Constitution and put beyond the reach of parliament — the public would be aware that the rights were being infringed. There could be no argument that the limitation of these rights was reasonably justified in a democratic society.

Most civil and political rights can be limited in the public interest or for the common good or to accommodate the conflicting rights of others. Nowadays the limit on such rights is usually determined by inquiring what is demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. This would be Parliament's call. Under the dialogue model we have proposed, courts could express a contrary view. But ultimately it would always be Parliament's call. This makes it a very different situation from the US where under a constitutional model judges have the final say.

Some politicians have been suggesting that they or their colleagues would be too timid to express a view contrary to the judges and thus the judges in effect would have the last word on what limits on rights are demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. Such timidity is not my experience of Australian politicians. Afterall if the contest is about what is justified in a free and democratic society, who is better placed than an elected politician to claim that they know the country's democratic pulse on the legitimate limit on any right?

To elaborate a little more on our model (which is similar to the one adopted in Victoria and the ACT), let me respond to two specific criticisms offered by Senator George Brandis SC when our report was released. On ABC Radio, the Shadow Attorney General referred to one of the derogable rights we list: the right to freedom from forced work. He said:

[T]hat sounds fair enough, but let us say Australia were at war. Now, in three of the wars that Australia has fought in — the First World War, the Second World War and the Vietnam War — the government of the day introduced military conscription. Now, if Australia were at war once again and the government of the day wanted to introduce military conscription, a person who objected to that might say, well, this is a violation of the prohibition against forced labour. So the decision about whether or not there should be military conscription in wartime would be a decision no longer made by the elected government, no longer made by the Parliament, but made by unelected judges.

With all respect to the learned senior Counsel, the decision would not rest with unelected judges. I would be horrified if it did. Parliament would pass a law authorizing conscription. A disaffected citizen might challenge the law in the courts. The court would be required to interpret the conscription law consistent with its purpose. The Human Rights Act would provide no basis for the court to find that the law was invalid. The court might venture to suggest that the law interferes with the right in an unwarranted way. We are not dealing with a US court that could strike down the law. The court would be most likely to find that the interference with the right to freedom from forced labour was demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. There is just no issue here with threatening the sovereignty of parliament. If a judge were to say the law was unwarranted, though valid, all the politicians need to do is say, 'We make the laws; we decide when conscription is needed; we wear the rub at election time; the judge is talking through his wig.' The judges would propose no threat to conscription. The court process would however require the government to explain rationally the need for restriction on the right to freedom from forced labour.

Senator Brandis gave one more example:

Another of the rights that Father Brennan recommends should be included in the Bill of Rights is the right to marry and found a family. Now, these rights obviously have to be enjoyed equally by everyone in Australia. We've been having a debate in this country for a few years now about gay marriage. Wherever you stand on the issue of gay marriage — whether you take a liberal view that there's nothing wrong with it, or a more conservative view that marriage is a relationship that can only really exist between a man and a woman — that is a decision that should be made by people whom the public elect, not by unelected judges.

I agree completely with Senator Brandis. Under the model of Human Rights Act we have proposed that decision would still be made by the people whom the public elect. A gay or lesbian couple disaffected with the Commonwealth marriage law might challenge it in court. But the court would be required to find that a law restricting marriage to a man and a woman was valid. The Human Rights Act would provide no basis for the court to find that the law was invalid. The court might offer an observation about whether that 'restriction' on the right to marry and found a family is justified in a free and democratic society. Once again it would be a matter for the parliamentary committee on human rights to decide whether to require the Attorney-General to provide an explanation of the existing law. The law could be changed only by the elected parliament. This is the virtue of the so called 'dialogue model'.

The new Commonwealth human rights machinery — the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011

As you all know, our elected leaders decided to put a Human Rights Act on the long finger. But they did legislate to provide for statements of compatibility and for a parliamentary committee on Human Rights. The Commonwealth Parliament's Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011, having passed the Senate on the final sitting day last year and having received royal assent over the summer, came into effect early this year. The Australian Parliament has now appointed a ten member Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights which is required to examine Bills and legislative instruments 'for compatibility with human rights'. It is chaired by ex-speaker Harry Jenkins. The Committee may also examine existing Acts and inquire into any matter relating to human rights 'which is referred to it by the Attorney-General'. 'Human rights' are defined to mean 'the rights and freedoms recognised or declared' by the seven key international human rights instruments on civil and political rights, economic, social and cultural rights, racial discrimination, torture and other cruel inhuman or degrading treatment, including the Conventions on women, children and persons with disabilities. Anyone introducing a Bill or legislative instrument to Parliament will now be required to provide 'a statement of compatibility' which 'must include an assessment of whether the Bill (or instrument) is compatible with human rights'.

So at a national level, the Executive and the Legislature cannot escape the dialogue about legislation's compliance with UN human rights standards. Neither can the courts, because Parliament has already legislated in the Acts Interpretation Act that 'in the interpretation of a provision of an Act, if any material not forming part of the Act is capable of assisting in the ascertainment of the meaning of the provision, consideration may be given to that material'. Parliament has provided that 'the material that may be considered in the interpretation of a provision of an Act' includes 'any relevant report of a committee of the Parliament' as well as 'any relevant document that was laid before, or furnished to the members of, either House of the Parliament by a Minister before the time when the provision was enacted'22. Clearly reports of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights and the statements of compatibility provided by the Executive will be relevant in court proceedings in determining the meaning of new Commonwealth statutes which impinge on internationally recognised human rights and freedoms. Victorian lawyers should be well positioned to providing the new parliamentary committee and the courts with assistance in utilising these new interpretative mechanisms.

That's not all. The Gillard Government's human rights framework notes that 'the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 enables a person aggrieved by most decisions made under federal laws to apply to a federal court for an order to review on various grounds, including that the decision maker failed to take into account a relevant consideration'. Ron Merkel QC in his submission to the National Human Rights Consultation pointed out that the High Court has already 'recognised the existence of a requirement to treat Australia's international treaty obligations as relevant considerations and, absent statutory or executive indications to the contrary, administrative decision makers are expected to act conformably with Australia's international treaty obligations'.

I believe that ultimately Australia will require a Human Rights Act to set workable limits on how far ajar the door of human rights protection should be opened by the judges in dialogue with the politicians. We will now have a few years of the door flapping in the Canberra breeze as public servants decide how much content to put in the statements of compatibility; as parliamentarians decide how much public access and transparency to accord the new committee processes; and as judges feel their way interpreting laws consistent with the parliament's intention that all laws be in harmony with Australia's international obligations, including the UN human rights instruments, unless expressly stated to the contrary. There is no turning back from the federal dialogue model of human rights protection.

The Executive has been a little testy during the initial teething period for these reforms. The Government took a dim view of the parliamentary committee wanting to scrutinise amendments to the federal intervention in the Northern Territory given that the amending bills were introduced before the new human rights machinery was put in place. When passing new laws to resurrect offshore processing of asylum seekers, the government used the artifice of introducing amendments to an already existing bill so as to avoid the need for providing a statement of compatibility and so as to keep the contested legislation away from the parliamentary committee. But over time, the number of dormant pre-human rights bills will dry up, and all future bills will need to run the gauntlet. For example, should government ever proceed with the so-called Malaysia solution, it will be interesting to see how they rationalise the transfer of unaccompanied minors to Malaysia given the requirement of Article 3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child that 'In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.'

In his first report to Parliament on 22 August 2012, the Chair of the Committee Harry Jenkins MP said:

The committee considers that the preparation of a statement of compatibility should be the culmination of a process that commences early in the development of policy, and not as a 'tick-box' exercise at the end. In this way, a statement of compatibility can reasonably be expected to reflect in appropriate detail the assessment of human rights that took place during the development of the policy and the drafting of the legislation. The statement of compatibility should take the objective of the proposed legislation as its point of reference, identify the rights engaged, indicate the circumstances in which the legislation may promote or limit the rights engaged and set out the justification for any limitations, in an appropriate level of detail, together with any safeguards provided in the legislation or elsewhere.

In his second report on 12 September 2012, he said:

[T]he committee has considered nine bills introduced during the period 14 August to 23 August 2012 and 146 legislative instruments registered with the Federal Register of Legislative Instruments between 23 July and 22 August 2012.

In his third report on 19 September 2012 he said:

The committee notes that one bill appears to have been introduced without a statement of compatibility. The committee considers that this bill does not appear to raise any human rights concerns. However, the committee will draw the Minister's attention to the requirement in the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 that each bill and legislative instrument introduced into the Parliament must be accompanied by a statement of compatibility. Statements of compatibility must be provided for all bills and all legislative instruments regardless of whether the proposed legislation is considered to raise human rights issues or not.

In his fourth report and fifth reports he reiterated:

In particular, the committee would prefer for statements to provide information that addresses the following three criteria:

- whether and how the limitation is aimed at achieving a legitimate objective;

- whether and how there is a rational connection between the limitation and the objective;

- whether and how the limitation is proportionate to that objective.

ACOSS made a spirited and well researched submission to the committee that the Social Security Legislation Amendment (Fair Incentives to Work) Bill 2012 failed to comply with international human rights protections including article 9 of the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which recognizes 'the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance'.

ACOSS was joined by the Australian Human Rights Centre, the National Council of the St Vincent de Paul Society, the National Welfare Rights Network, the Welfare Rights Centre and the National Council of Single Mothers and their Children.

The Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations submitted to the Committee:

The Department considers that the measure maintains a person's right to social security as per article 9 of the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), as that right has been interpreted in the General Comments on the ICESCR (see particularly paragraphs 9 to 27).

In Australia only 50 per cent of single parents are in work, well below the OECD average of 60 per cent. Single parents make up around 70 per cent of jobless families.

John Falzon, the CEO of St Vincent de Paul has put a very different interpretation on the new law noting:

The fundamental flaw of this legislation is that, though it will result in a saving of $728 million over four years, it will do nothing to assist sole parents into employment. It will result in a decline in the availability of some of the supports that might have been available on the Parenting Payment, and a weekly cut of between $65 and $115.

It can only be of benefit to advocates like yourselves that you now have access to a new avenue in the legislative process for agitating the human rights of your constituents including economic and social rights. All of us have a role to play as the committee determines the limits of its competence and discretion to upset policy balances set by the Executive especially when it comes to the progressive realization of economic and social rights bearing in mind the distinctive Article 2 of ICESCR which provides:

Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures.

In his fourth report to Parliament, Harry Jenkins reported just on this piece of welfare legislation and said:

Through this bill the government seeks to provide greater incentives and opportunities for Parenting Payment recipients, particularly for single parents, to re-engage in the workforce and to provide greater equity and consistency in the eligibility rules for Parenting Payments. The committee considers that these are legitimate objectives.

However the committee notes that it does not necessarily follow that the measures seeking equity are justified, as it is not apparent to the committee that the government has considered any alternative options in this regard.

With regard to the question of whether there is a rational connection between the measures and the objective, the committee's examination of the available evidence indicates that this is not a matter that can be conclusively proven up front. The committee considers that on balance, the government has provided sufficient supporting evidence to suggest that the proposed measures may go some way in achieving the stated objectives.

However, the committee considers that the lack of decisive evidence highlights the need for appropriate monitoring mechanisms to accompany the proposed changes. The committee notes that it is not apparent that the government has taken steps to establish post-legislative mechanisms to evaluate whether the measures are indeed achieving their objectives or to monitor their impact on individuals and groups, particularly with regard to the risks of hardship and discrimination.

The committee notes that proportionality requires that even if the objective of a limitation is of sufficient importance and the measures in question are rationally connected to the objective, it may still not be justified, because of the severity of the effects of the measure on individuals or groups.

In his fifth report to Parliament on 10 October 2012, Harry Jenkins noted:

To date the committee has requested further clarification in relation to 16 bills and seven instruments considered in its First, Second and Third reports. The committee has received responses to six of these requests and is therefore waiting for responses in relation to 12 bills and five instruments considered in its First, Second and Third Reports. This falls well short of the committee's expectations and I urge the Ministers, Members and Senators concerned to take urgent action in respect of any outstanding responses. I would like to emphasise the desirability of the committee considering such responses prior to the conclusion of the Parliament's consideration of the legislation. It is a source of disappointment to the committee that two of the bills for which it has sought further information have now been passed by the Parliament. Notwithstanding the passage of these bills, the committee still expects the relevant Ministers to provide a response to the committee's request and will be writing to them accordingly.

Addressing the 2012 Australian Government and Non-Government Organisations Forum on Human Rights, on 14 August 2012, Jenkins said:

The committee does not want to see Statements of Compatibility outsourced to legal specialists, nor does it want them to be seen as mere procedural hurdles at the end of the drafting process. The committee wishes to see consideration of human rights genuinely elevated in the policy development process. The committee considers that the requirement for Statements of Compatibility has the potential to instill a culture of human rights in the federal public sector by integrating the consideration of human rights into the development of policy. Cultural change requires patience and constructive support. For its part the committee intends to approach its role in a considered and responsible way by seeking to foster an effective dialogue with the Executive and Departments.

I urge all who represent the interests of poor and disadvantaged Australians to familiarize yourselves with the workings of this committee. It is not a sole preserve of lawyers. Human rights language can be helpful in agitating questions of equity and social justice, especially when the major political parties are competing to bring in a budget surplus. This committee provides you a place at the table, even when seeking protection of economic and social rights including health, housing, education, and social security.

The above text is from Fr Frank Brennan SJ's address 'Advancing human rights in Australia — lessons from the National Human Rights Consultation' at the 'Human Rights Matters!' conference marking Anti-Poverty Week 2012. 17 October 2012, Cardinal Knox Centre, St Patricks Cathedral, Melbourne.

The above text is from Fr Frank Brennan SJ's address 'Advancing human rights in Australia — lessons from the National Human Rights Consultation' at the 'Human Rights Matters!' conference marking Anti-Poverty Week 2012. 17 October 2012, Cardinal Knox Centre, St Patricks Cathedral, Melbourne.